Traffic Cones and Flashing Lights

Question: How many traffic cones does it take to stop a speeding car?

Yes, the barriers we use are flimsy, and a traffic cone will not stop an errant vehicle from driving into a work zone. But there are some tweaks we can make to the equipment we use that will improve the level of protection workers on the street can get out of the resources available. Yet even with all our preparations, there is always a worst-case event dramatized by a recent news photo of an errant car, upside down on a bucket truck that was on a right-of-way well off the highway. It is the reason that OSHA and other regulating authorities expect employers to train all employees, specially train supervisory employees and provide the equipment necessary to protect workers as much as possible. We can’t build car-proof barriers, so the best protection is to be proactive by preventing incidents in the first place.

In this installment of “Train the Trainer 101,” we are going to look at practical protection of workers on the street, with particular attention paid to the people on the other side of your work zone practices: passing motorists. I have been observing work zones for decades. I drive through them and past working crews every week. I also investigate highway incidents and have had occasion to provide expert witness analysis in both civil litigation and regulatory cases involving highway work zones.

TTC and the MUTCD

Across the United States, the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices is the primary regulating document for temporary work zones and controls. It is currently in its 10th edition with two revisions, the latest being a PDF version dated May 2012. The MUTCD is a U.S. Department of Transportation and Federal Highway Administration adopted standard. Helpful vendors would love to sell you their commentary versions of the MUTCD, but it is free on the web at https://mutcd.fhwa.dot.gov/kno_2009r1r2.htm. Keep in mind that, when you select the version you’re going to use, the PDF from the U.S. DOT website is the only official version. In fact, even the HTML version available on the DOT website has irregularities, so the website posts this guidance to users: “The PDF files constitute the official version of the MUTCD and always take precedence over any potentially conflicting MUTCD text or figures that may occur in the HTML files.”

The 11th edition of the MUTCD is in revision now. Comments for the revision are closed but are about 35,000 in number. The next edition is due to be released in May 2023. For those readers who are new to safety administration and not familiar with the MUTCD, the manual contains standards and regulations on traffic control devices, signs and methods. Part 6 is the section on temporary traffic control (TTC).

The whole objective of Part 6 is establishing TTC that safely guides pedestrians, cyclists and drivers through a space where construction activities or incident response has compromised the regular routes of travel. In my audits of TTC, I have found that most setups are moderately effective at directing vehicular traffic, but pedestrians and cyclists are rarely properly addressed. The result is that cyclists and pedestrians are at risk, creating liability for the employer. When vehicular traffic is poorly controlled, it creates hazards and deadly risks for the employees behind those controls. The key to creating good TTC is to view your setup from the perspective of the drivers. A driver is accustomed to white lines and curb markers, speed limit signs and red lights. Drivers may become indecisive when they suddenly come upon temporary signs and traffic cones directing them against those commonly expected controls. When TTC is insufficiently announced via warning signs and/or poorly defined by cones and flaggers, workers are endangered. In the power-line business, there is another aggravating factor, and that is the work itself. Road building is a pretty boring scene. Booms in the air with people aloft, coverup colors and rigging are attention-grabbers that further distract driver attention from the cones and signs that are intended to direct them through the constricted space. That combination adds up to increased chances of an incident. The warning signs and controls must be clear and robust to be effective. It is imperative that your crews drive through the work zone and examine the effectiveness of the lane markers and signs from the perspective of drivers to see if improvements are needed. It is also important to remember that the guidance of the MUTCD is minimum performance guidance.

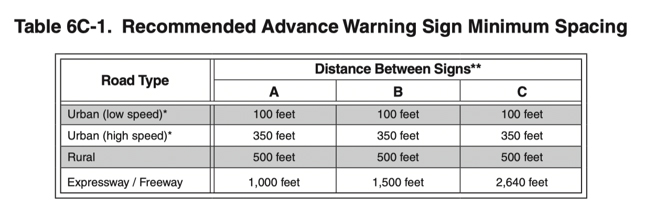

The first element of TTC improvement is the advance warning sign, especially proper placement. MUTCD Table 6C-1 is a guide for placement of advance warning signs.

The first mistake we tend to make relates to column A above. Each distance listed in the column is the distance the first sign away from the TTC should be placed. This distance is from the point of deviation of traffic established by the first cones drivers will encounter. A placement is often mistakenly made a distance from the first trucks, not the lane change. This mistake reduces reaction time, but if the next two signs are spaced from the misplaced column A location, the whole advance warning system reduces awareness and the reaction time of drivers.

An important training note: It can be just as hazardous to place advance warning signs as it is to have a poorly designed TTC zone. Workers placing advance warning signs, especially on curving, tree-lined or hilly terrain, have been hit by drivers almost as often as workers in TTC zones. The MUTCD features Table 6C-2, titled “Stopping Sight Distance as a Function of Speed.” This table is intended as a guide to assist planners in the placement of elements of traffic control systems. Employers should be training their personnel in sign placement distance, but they should also clearly remind workers that speed, for the purposes of safety, is not what the posted limit states. Speed limits are devised based on off-peak normal traffic density, not on to-work or from-work traffic congestion times. Speed determination is also subjective based on the theory of the 85th percentile. This measure refers to the actual speed 85% of drivers will attain based on their confidence and comfort with the road surface quality, roadway width, roadway markings, shoulder width, vision distance, curves and hills, weather conditions, daylight, and density of trees or foliage lining the roadway. All of these elements affect a driver’s confidence and comfort, leading to the speed they will attain under those conditions. The rest of the matrix assumes 10% of drivers will drive slower than the 85%, and 5% of drivers will exceed the speed of the 85th percentile. Left out of this subjective measure is the number of drivers texting and the 60% of drivers under some measure of impairment after 11 p.m. on any given Friday or Saturday. Adding distance to the warning system, making the notifications and using robust channelizing devices boost the aware-time reaction of drivers heading toward your crews.

Pedestrians and Cyclists

Advance warning for pedestrians is often an issue. We find “Sidewalk Closed” signs right at the beginning of the traffic control zone – 100 yards after the nearest alternate pedestrian road crossing by the work area. Few pedestrians, especially older individuals, are going to backtrack over a distance to reroute their path. They are more likely to try and navigate the traffic space, raising risks for everyone. Traffic work zone supervisors and planners should be aware that the Americans with Disabilities Act makes clear the requirements for maintaining safe wheelchair passage through your work zone. This applies where handicapped persons are likely to come upon your work area. If they are there, you must have a solution for their safe transit through the area. A solution that addresses both pedestrians and cyclists is closing the space to both, with signage ahead of the nearest alternate route so that they can take the alternate route with little inconvenience. By the way, check that alternate route. If you close a safe pathway for your work zone and direct them through an unsafe pathway, you may find yourself liable for creating a hazard for pedestrians when you were trying to do just the opposite.

Channelizing devices are the cones and barrels placed along the roadway to guide traffic through the work zone. The MUTCD states that a short taper, having a minimum length of 50 feet and a maximum length of 100 feet with channelizing devices at approximately 20-foot spacing, should be used to guide traffic into the one-lane section. The issue here is that a short taper of 100 feet with cones spaced 20 feet apart equates to five traffic cones. While the five cones meet the standard, there is a very good reason to use a 3-foot separation – and that is the function of the traffic cones or, better, the real value of cones. The cones are principally a visual device. They can’t stop an errant vehicle unless they are in the back of a trailer hooked to a truck. What they can do is make noise. If you place cones 3 feet apart, the errant driver striking them is going to hear the cones and feel them in the steering wheel. If they are distracted, they will immediately become aware and react. To workers, a car striking cones provides a loud, early warning that something is wrong, giving them more time, even if only seconds, to take evasive action.

We have only discussed a few practical issues commonly discovered in inspections and accident investigations. Chapter 6 of the MUTCD has lots of requirements and guidance for employers, and we should be taking advantage of it to protect workers who operate near highways.

OSHA and Work Zones

OSHA has authority over work zones. They do not investigate traffic incidents, but they do investigate work zone incidents and work zone safety complaints, and the agency can self-initiate an inspection if hazards are observed while driving by a work zone.

One of the first instructions to the compliance officer is to drive through the work zone, observing for the timely and clear direction and channelization of the driver through the work zone. This training of compliance officers has usually been the issue that has resulted in self-initiated inspections. OSHA has published CPL 02-01-054, “Inspection and Citation Guidance for Roadway and Highway Construction Work Zones” (see www.osha.gov/enforcement/directives/cpl-02-01-054). The agency can and will cite employers for violations of the MUTCD, as clearly stated in the CPL. OSHA regulations on work zones are few and generalized, usually referencing compliance with the millennium edition (year 2000) of the MUTCD. The bottom line here is that failing to meet the minimum requirements of the MUTCD can be the basis for an OSHA violation as well as an inspection.

Flashing Lights

The MUTCD has no specifications or requirements for flashing lights. Many city, state and county regulations that amend the MUTCD standards for their jurisdictions require flashing or strobe lights on mobile equipment in work zones. DOT contracts also have requirements for conspicuity and the use of strobes on work vehicles in a work zone.

The problem with flashing lights is the same as the problem with backup alarms. The more you are exposed to flashing lights and alarms, the less noticeable the warning devices become. We may be getting to the saturation point with flashing lights. Adding to that saturation of light is the placement of vehicles in the work area. In observations, I have noticed that little consideration is paid to vehicles not being used in an operation, particularly during these past two years when we have added to the numbers of trucks in work zones due to a greater number of single drivers during COVID. Now we have numerous trucks parked wherever they will fit, and all of them are running yellow strobes. This creates distractions for drivers. I also see trucks parked on both sides of the road when all the work is only on one side. This keeps passing drivers looking for hazards on both sides of the road when only one side really represents moving equipment risks. Where you can plan it, avoid dividing drivers’ attention by reducing unnecessary distractions in the work area.

The bottom line for employers is summed up in MUTCD rule 6D.03.03.A: “All workers should be trained on how to work next to motor vehicle traffic in a way that minimizes their vulnerability. Workers having specific TTC responsibilities should be trained in TTC techniques, device usage, and placement.”

Take a critical look at your traffic control program and training. See if they really meet the safety needs of the workers on the ground and the interest of the public.

About the Author: After 25 years as a transmission-distribution lineman and foreman, Jim Vaughn, CUSP, has devoted the last 24 years to safety and training. A noted author, trainer and lecturer, he is a senior consultant for the Institute for Safety in Powerline Construction. He can be reached at jim@ispconline.com.