Advancing Safety: Incident Prevention Explores the Latest in Roadway Protection at American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA) 2026!

Unsafe Compliance: Why Checking Boxes Won’t Save Lives

Utility Safety Podcast – Deep Dive – Using Safety to Drive Operational Excellence – Written By Doug Hill, CUSP

Hot Spots on Energized Switches: What They Signal, What Causes Them, and What Utilities Can Do Without Creating Unnecessary Outages

SPONSORED BY FIRSTPOWER GROUP

March 12th, 2026 @ 1PM ET

Hot Spots on Energized Switches: What They Signal, What Causes Them, and What Utilities Can Do Without Creating Unnecessary Outages

Which will include:

- Hot Spot Interpretation: Understand that thermal anomalies signify underlying system failures, not just elevated temperatures.

- Root Cause Analysis: Identify primary drivers of hot spots, such as mechanical resistance, corrosion, contamination, and lubricant failure.

- Field Recognition: Recognize early physical warning signs in the field to prevent equipment escalation or failure.

- Mitigation Strategy: Evaluate critical decision points to determine if a fix requires an outage or can be handled while energized.

- Standardized Framework: Implement the Identify → Verify → Stabilize → Prevent workflow for consistent issue management.

- Maintenance Optimization: Adopt best practices in lubrication and record-keeping to minimize repeat issues and improve switch reliability.

Medical-Grade Cooling Vest

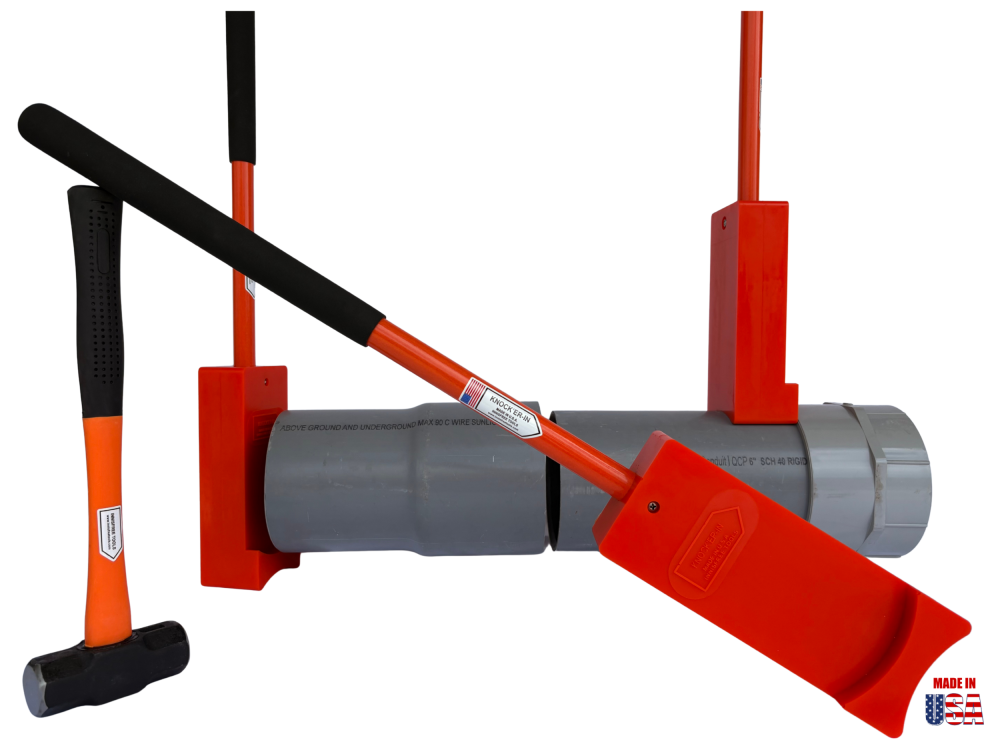

Underground Conduit Installation Tool

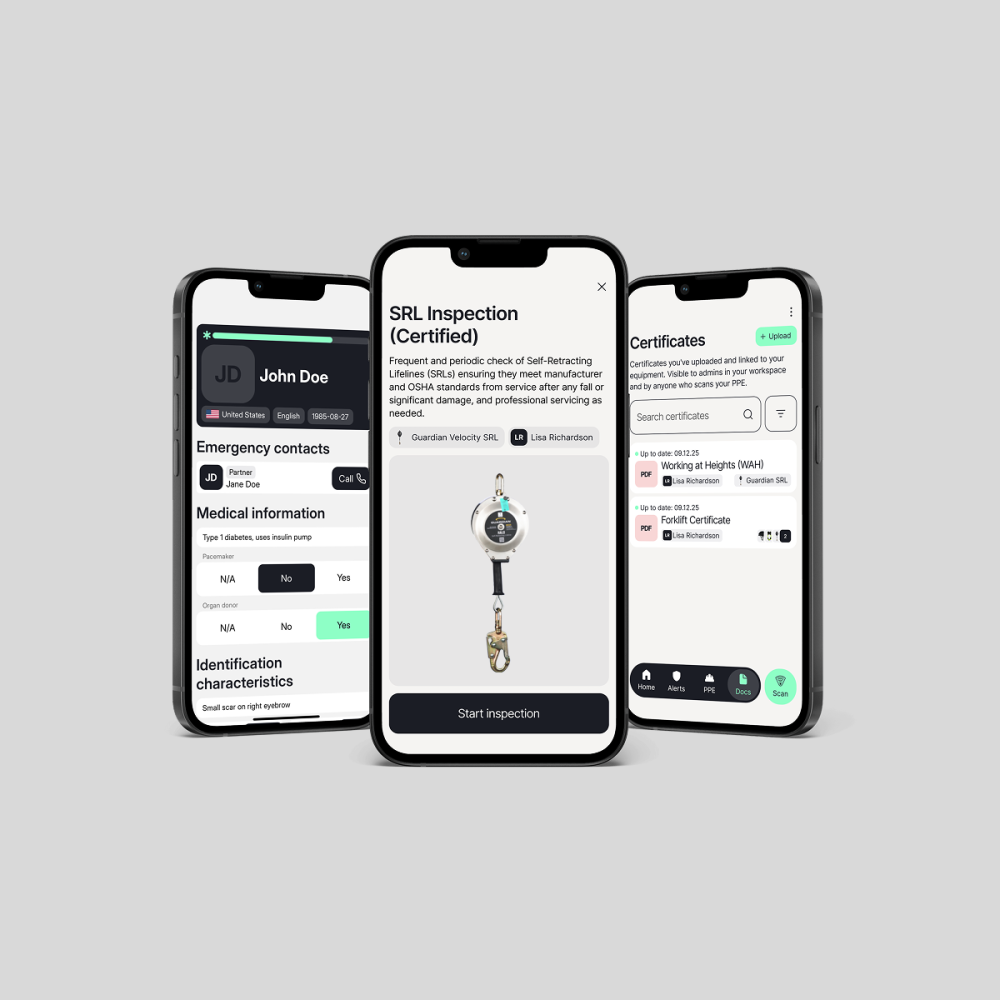

SRLs with Digital Safety Protection

Ground Protection and Access Mats

Self-Rescue System

The Human Tuning Fork: Harnessing Frequency and Vibration for Utility Safety with Bill Martin, CUSP

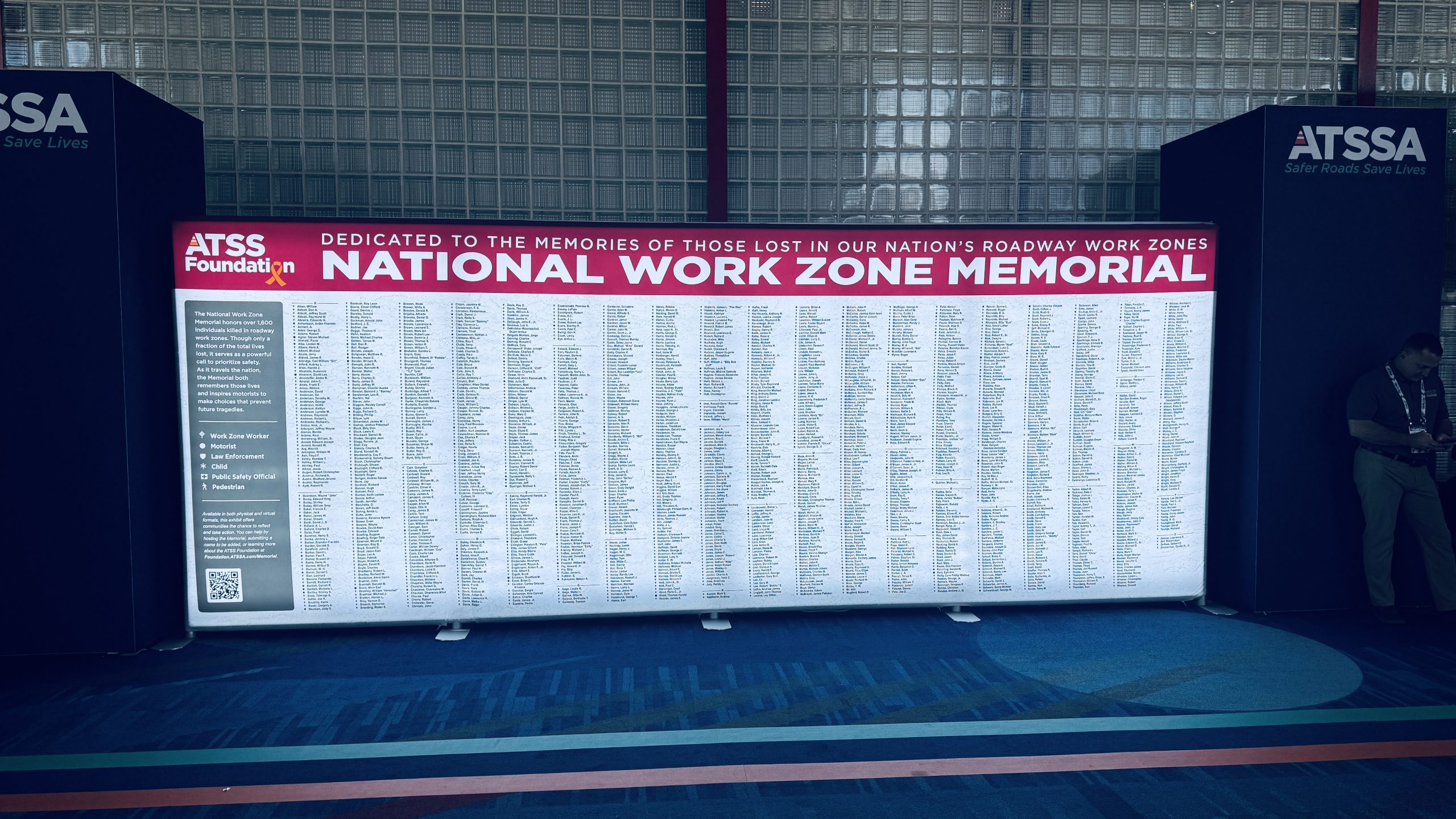

Advancing Safety: Incident Prevention Explores the Latest in Roadway Protection at American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA) 2026!

In the News

Unsafe Compliance: Why Checking Boxes Won’t Save Lives

Utility Safety Podcast – Deep Dive – Using Safety to Drive Operational Excellence – Written By Doug Hill, CUSP

Hot Spots on Energized Switches: What They Signal, What Causes Them, and What Utilities Can Do Without Creating Unnecessary Outages

Medical-Grade Cooling Vest

Underground Conduit Installation Tool

SRLs with Digital Safety Protection

Ground Protection and Access Mats

Self-Rescue System

Opinion

Advancing Safety: Incident Prevention Explores the Latest in Roadway Protection at American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA) 2026!

Unsafe Compliance: Why Checking Boxes Won’t Save Lives

Utility Safety Podcast – Deep Dive – Using Safety to Drive Operational Excellence – Written By Doug Hill, CUSP

Hot Spots on Energized Switches: What They Signal, What Causes Them, and What Utilities Can Do Without Creating Unnecessary Outages

Video

Advancing Safety: Incident Prevention Explores the Latest in Roadway Protection at American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA) 2026!

Featured Topics

Advancing Safety: Incident Prevention Explores the Latest in Roadway Protection at American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA) 2026!

Unsafe Compliance: Why Checking Boxes Won’t Save Lives

Utility Safety Podcast – Deep Dive – Using Safety to Drive Operational Excellence – Written By Doug Hill, CUSP

Hot Spots on Energized Switches: What They Signal, What Causes Them, and What Utilities Can Do Without Creating Unnecessary Outages

Medical-Grade Cooling Vest

Underground Conduit Installation Tool

Advancing Safety: Incident Prevention Explores the Latest in Roadway Protection at American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA) 2026!

For utility safety and operations professionals, the intersection of roadside work and live traffic remains one of the highest-risk environments. To stay at the forefront of hazard mitigation, Incident Prevention is on-site in Houston for the ATSSA Annual Convention & Traffic Expo, evaluating the next generation of life-saving technologies.

From AI-enabled work zone intrusion alarms to the newest MASH-compliant barriers, the innovations showcased at the ATSSA Expo are critical for any organization committed to “Target Zero” incidents.

Our team is specifically looking at:

- Connected Work Zones: Real-time digital alerting systems that bridge the gap between utility crews and motorists.

- Advanced PPE & Visibility: High-performance gear designed to ensure workers are seen in all weather and lighting conditions.

- Fleet Safety Innovations: New vehicle lighting and attenuator technologies that protect the mobile work zone.

Integrating these solutions into your Safety Management System (SMS) isn’t just about compliance; it’s about evolving your safety culture from a priority to a fundamental value. For a complete look at the exhibitors and the New Products Rollout, visit the official ATSSA Expo website.

-

IMG_7569

-

IMG_7570

-

IMG_7591

-

IMG_7585

-

IMG_7584

-

IMG_7582

-

IMG_7583

-

IMG_7577

-

IMG_7574

-

IMG_7573

Unsafe Compliance: Why Checking Boxes Won’t Save Lives

Utility Safety Podcast – Deep Dive – Using Safety to Drive Operational Excellence – Written By Doug Hill, CUSP

Hot Spots on Energized Switches: What They Signal, What Causes Them, and What Utilities Can Do Without Creating Unnecessary Outages

SPONSORED BY FIRSTPOWER GROUP

March 12th, 2026 @ 1PM ET

Hot Spots on Energized Switches: What They Signal, What Causes Them, and What Utilities Can Do Without Creating Unnecessary Outages

Which will include:

- Hot Spot Interpretation: Understand that thermal anomalies signify underlying system failures, not just elevated temperatures.

- Root Cause Analysis: Identify primary drivers of hot spots, such as mechanical resistance, corrosion, contamination, and lubricant failure.

- Field Recognition: Recognize early physical warning signs in the field to prevent equipment escalation or failure.

- Mitigation Strategy: Evaluate critical decision points to determine if a fix requires an outage or can be handled while energized.

- Standardized Framework: Implement the Identify → Verify → Stabilize → Prevent workflow for consistent issue management.

- Maintenance Optimization: Adopt best practices in lubrication and record-keeping to minimize repeat issues and improve switch reliability.

Medical-Grade Cooling Vest

Advancing Safety: Incident Prevention Explores the Latest in Roadway Protection at American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA) 2026!

Unsafe Compliance: Why Checking Boxes Won’t Save Lives

Utility Safety Podcast – Deep Dive – Using Safety to Drive Operational Excellence – Written By Doug Hill, CUSP

Hot Spots on Energized Switches: What They Signal, What Causes Them, and What Utilities Can Do Without Creating Unnecessary Outages

Advancing Safety: Incident Prevention Explores the Latest in Roadway Protection at American Traffic Safety Services Association (ATSSA) 2026!

Unsafe Compliance: Why Checking Boxes Won’t Save Lives

Utility Safety Podcast – Deep Dive – Using Safety to Drive Operational Excellence – Written By Doug Hill, CUSP

Hot Spots on Energized Switches: What They Signal, What Causes Them, and What Utilities Can Do Without Creating Unnecessary Outages

Most Popular

We use cookies and similar technologies to improve your experience on our website.