The Antidote to Complacency and Familiarity

Safety managers know that when an employee has done a particular task many times, that individual can become so familiar with the action that they no longer have to pay close attention while performing the work. As they become complacent in their ability to successfully complete the task, the risk of accident increases. But familiarity is not an emotional state. It’s a physical condition. Familiarity is the byproduct of habit, and a habit is a neural pathway created in the brain through repetition.

How Habits are Formed

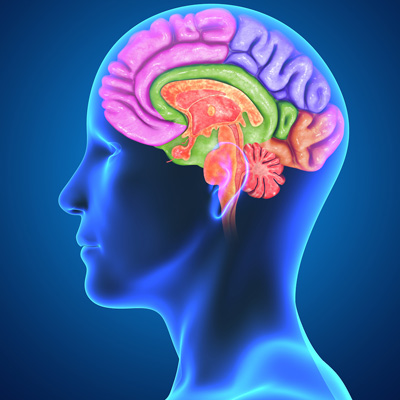

When the brain does something for the first time, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) is activated and communicates in a loop with the striatum.

The PFC is the part of the brain that sits above the eyeballs. It’s essential in making decisions, planning ahead, focusing thoughts, paying attention, learning and considering several different yet related lines of thinking. It’s used for evaluating the future consequences of current activities, working toward a defined goal, predicting outcomes, interpreting social cues, moderating social behavior, and determining good and bad, better and best. The PFC helps retain information while performing a task, determine what information is relevant to the task in progress and keep the objective of the task in mind, all at the same time.

These behaviors make up a wish list of employee behavior. Just imagine how much safer and more productive your employees could be if they were using their PFC all the time. The PFC is advanced, powerful and an amazing safety resource, but it’s also intensive in its use of energy and effort. The brain does not want to fire up the PFC if it doesn’t have to or for any longer than it needs to.

The striatum is found in the center interior of the brain at the top of the brain stem. It is the habit, reward and goal-motivated behavior center of the brain.

When the brain is doing something new, it activates all the neurons along the path between the PFC and the striatum. It’s working hard to make sure you’re successful at this action. However, the brain is a quick learner. The next time it repeats that action, it’s a little more familiar. The brain doesn’t have to work quite as hard, so fewer neurons fire. Then you perform the action again and again, and it gets easier and easier. Fewer and fewer neurons fire. When a person has done something often enough that the action is habitual, the PFC is no longer required. It’s just the striatum. On top of that, it’s only the neurons at the beginning of the action and the end of the action that fire.

Habit Creation in Real Life

We’ve all experienced the habit creation process in our own lives. For example, I learned how to drive on a stick shift. Not only did I have to pay attention to the lights and signs and other drivers, but I was also learning how to press in the clutch, put the car in gear and then step on the gas while releasing the clutch with the right pressure. I sat through more than one green light in an utter panic, stalling my car over and over again. In the beginning, driving was stressful and overwhelming. All I could do was focus on driving. But now? I’ll be honest, I’ve gotten in my car in the driveway and arrived at my destination thinking, “I hope I stopped at every light because I don’t even remember driving!”

Once driving becomes a habit, the brain doesn’t have to work very hard; only the neurons at the beginning and the end of the action have to fire, and in the meantime, you can think about other things.

The Antidote to Habit

Habits are a double-edged sword. Sometimes habits can be good. For example, always wearing the appropriate PPE is a good habit to have. But a habit also can be dangerous, because it allows the brain to hang out in the striatum and function on autopilot, during which time it isn’t paying attention to what it’s doing or what is going on around it. For example, instead of focusing on the task at hand, your employee might be thinking about the fight they had with their spouse before they left the house that morning or what errands they need to run on their way home from work.

Mindfulness is the antidote to familiarity, complacency and habit. The term “mindfulness” gets tossed around a lot, but it’s simple: Mindfulness is noticing. It’s noticing thoughts, feelings, body sensations and the surrounding environment in the moment as they’re being experienced. Mindfulness is why someone can say, “It sounded wrong” or “The vibration felt off.” They stop work and avoid an imminent accident.

Mindfulness is the antidote to habit because it moves the brain from the striatum to the PFC and brings back online all of that advanced functionality. While meditation sometimes is equated with mindfulness, meditation actually is a mindfulness practice. Think of meditation as exercise for the mind. The body’s natural state is to lie still, so to exercise the body, you have to move it. The mind’s natural state is to move, so to exercise it, you must still it. Meditation can help create a stronger mindfulness muscle, which helps people be more mindful while out in the real world. But meditation isn’t the only mindfulness practice.

Mindfulness in the Moment

What I like to call “Mindfulness in the Moment” practices help you to short-circuit familiarity, complacency and habit, and to then bring the PFC back online. Following are two Mindfulness in the Moment strategies you can implement in your workplace immediately.

1. Ask questions. But do not ask yes or no questions. If you’ve ever asked someone a series of questions, and they answer so fast that you wonder if they’re even listening to what you’re saying, they’re not. Before the PFC can engage, the striatum chimes in with the answer. To prompt the brain to move back into the PFC, ask questions like, what would be a wise course of action? How would you manage this job if your child were doing the work? What could go wrong here? How can we do this so that if it goes wrong, no one gets hurt?

These types of questions can’t be answered by the striatum. They involve critical evaluation, during which time the PFC engages.

2. Control the breath. Breathing is a unique bodily function because it can be unconsciously or consciously directed. When breathing is unconsciously directed, the brain stem controls it. The brain stem is responsible for keeping you alive and provides other valuable services, such as the fight-or-flight response. It operates instinctively without a person’s conscious intention.

However, when a person consciously controls their breathing, the PFC is in charge. For this reason, the conscious manipulation of breath has been used by monks for centuries to calm and focus the mind.

There are dozens of different conscious breathing styles that can be used at strategic points during the workday or even while working that will trigger the PFC and prompt the mindfulness your employees need to stay safe on the job.

Tactical breathing is one such exercise that is taught to Navy SEALs and police officers throughout the U.S. It’s also referred to as “box breathing,” and the pattern is to inhale for a count of four, hold the breath in for a count of four, exhale for a count of four and hold out for a count of four. This pattern can be repeated a few times in a row or for several minutes at a time. It’s best to start with just a few repetitions and work up to longer durations as it’s actually quite difficult to do.

Conclusion

Familiarity and complacency are a result of ingrained neural pathways in the brain that allow employees to operate on habit and in the striatum part of their brain, but safety managers can strategically cause the PFC to engage by asking questions that require thoughtful evaluation or by directing employees to use exercises to consciously control their breath. Mindfulness can be another line of defense between your employees and an accident.

About the Author: Sharon Lipinski is the Habit SuperHero and CEO of Habit Mastery Consulting (www.habitmasteryconsulting.com), which helps organizations increase their targeted safety behavior by up to 150%. She is a Certified Corporate Wellness Specialist, certified CBT for insomnia instructor, speaker, TV personality and coach dedicated to helping people create the right habits so they can be happier, healthier and safer at home and in their work.