Understanding Step and Touch Potential

Summer storm season is upon us and with summer storms come downed wires, broken poles, and trees and branches that sometimes make contact with energized overhead conductors. This Tailgate covers some of the fundamental hazards of working on or around downed energized conductors, and the unseen hazard of step and touch potential.

What is Step and Touch Potential?

To understand step and touch potential, we first need to understand how energy dissipates across conductive objects. During broken pole or downed wire conditions, some really good conductors exist that provide path to ground including metal fences, wet soil and puddles. Other conductors exist that may not be so good, yet still allow current to travel to ground, such as trees, wood fences and utility poles. Wood is typically thought of as an insulator, but wet wood will conduct electric current.

When an energized conductor falls across a chain-link fence or directly to the ground, the object and immediate area become energized, creating a zone of high voltage in relation to the ground. The actual voltage depends on the source, resistance of the object and soil conditions, which include material and moisture.

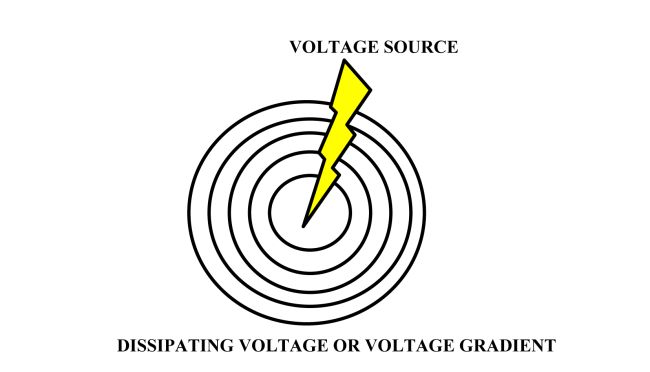

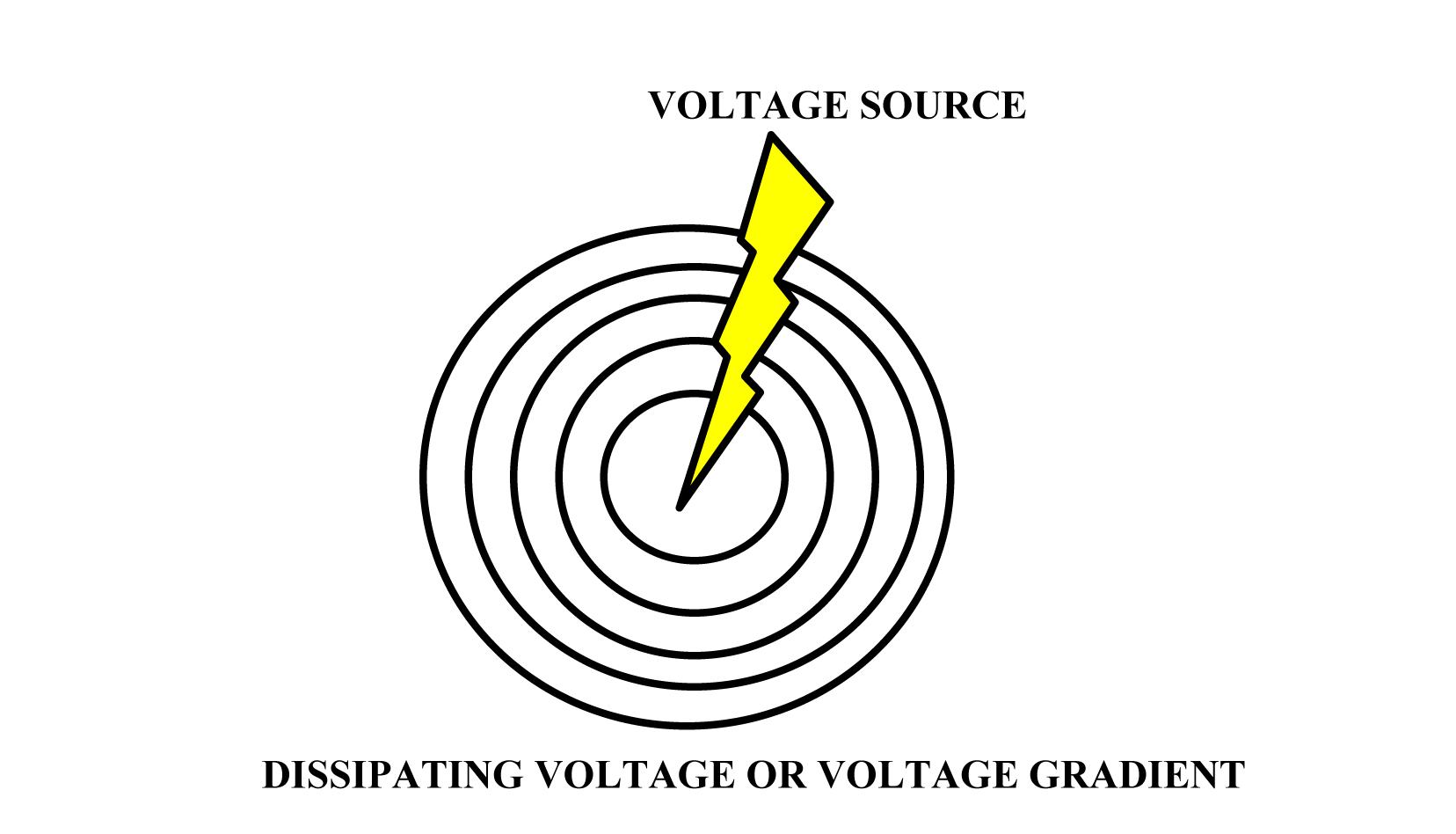

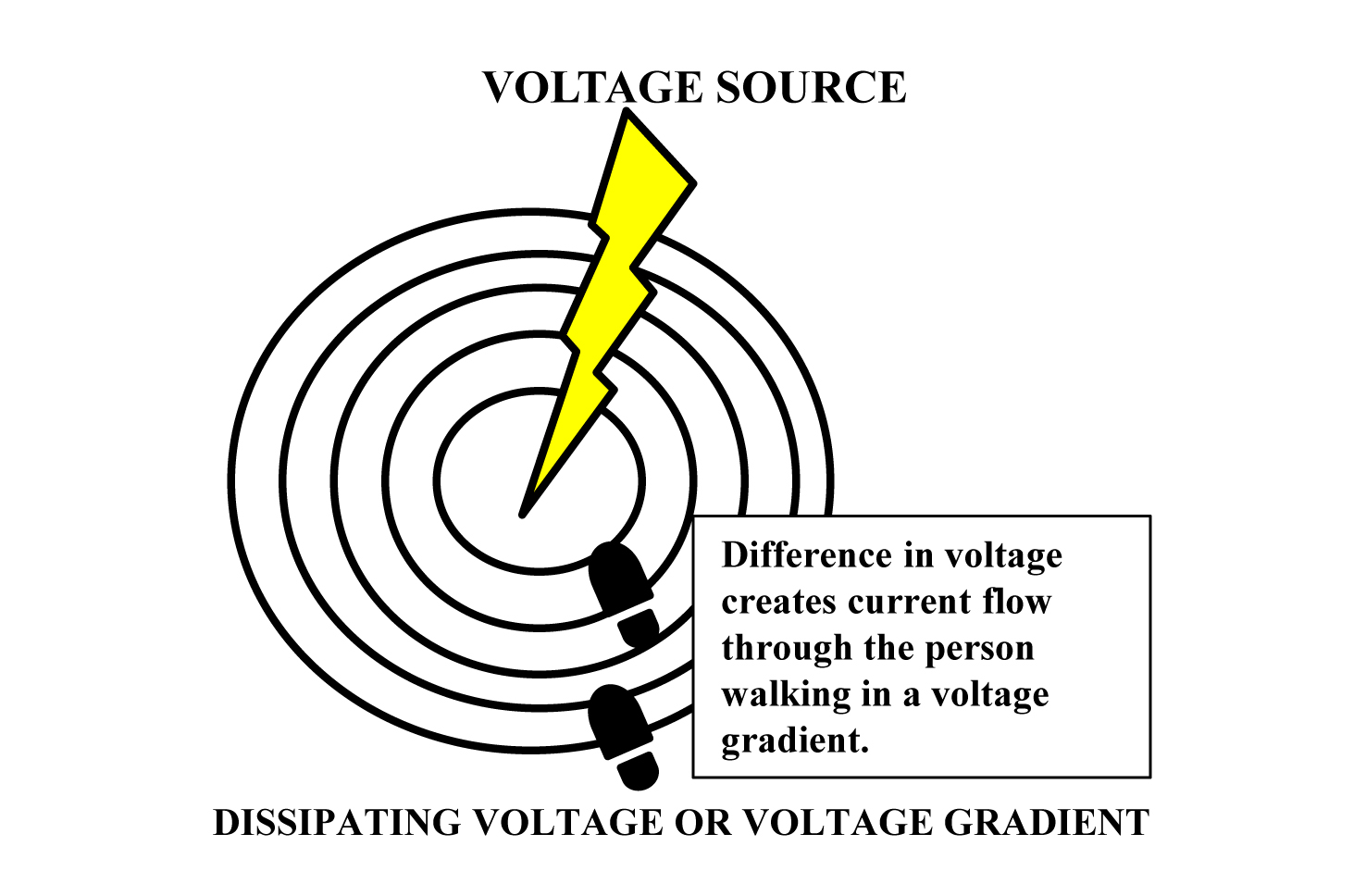

The dissipation of voltage from a grounded conductor – or from the grounded end of an energized grounded object – is called the ground potential gradient. Voltage drops associated with this dissipation of voltage are called ground potentials. The voltage decreases rapidly with increasing distance from the grounded end.

Another way of describing this is the example of a stone dropped in a pond. The stone creates ripples that eventually fade as they move from the center. Voltage is highest at the source and fades as the energy moves across the ground.

Step Potential

When current is flowing from an overhead conductor through a chain-link fence to the earth, a high-voltage condition is created and a voltage gradient will occur based on the resistivity of the soil, resulting in a voltage difference – also known as a potential difference – between two points on the ground. This is called a step potential as it can cause voltage difference between a person’s feet.

Touch Potential

Touch potential is the voltage between any two points on a person’s body – hand to hand, shoulder to back, elbow to hip, hand to foot and so on. For example, if an overhead conductor falls on a car, and a person touches that car, current could pass from the energized car through the person to the ground.

How to Protect Yourself

During storm conditions, the first thing to remember is that power lines may not be in proper configuration. For your protection, keep in mind these basic storm safety rules found in the OSHA Fact Sheet “Working Safely Around Downed Electrical Wires” (www.osha.gov/OshDoc/data_General_Facts/downed_electrical_wires.pdf):

• Do not assume that a downed conductor is safe simply because it is on the ground or it is not sparking.

• Do not assume that all coated, weatherproof or insulated wire is just telephone, television or fiber-optic cable.

• Low-hanging wires still have voltage potential even if they are not touching the ground, so don’t touch them. Everything is energized until tested to be de-energized.

• Never go near a downed or fallen electric power line. Always assume that it is energized. Touching it could be fatal.

• Electricity can spread outward through the ground in a circular shape from the point of contact. As you move away from the center, large differences in voltages can be created.

• Never drive over downed power lines. Assume that they are energized. And, even if they are not, downed lines can become entangled in your equipment or vehicle.

• If contact is made with an energized power line while you are in a vehicle, remain calm and do not get out unless the vehicle is on fire. If possible, call for help.

• If you must exit any equipment because of fire or other safety reasons, try to jump completely clear, making sure that you do not touch the equipment and the ground at the same time. Land with both feet together and shuffle away in small steps to minimize the path of electric current and avoid electrical shock. Be careful to maintain your balance.

By using your knowledge and a few basic storm safety rules, you can keep your crew and yourself out of harm’s way.

About the Author: John Boyle is vice president of safety and quality for INTREN, an electric, gas and telecommunication construction company based in Union, Ill. Boyle has more than 28 years of experience, and has worked in nuclear and wind power generation and electric and gas distribution.