A Historical Review of Workplace Safety in the U.S.

A Historical Review of Workplace Safety in the U.S.

While OSHA may sometimes make it difficult for businesses to do business, their rules are necessary for the safety of the American workforce.

Has OSHA ever made it difficult for businesses to do business? It sure has, and I will be the first to raise my hand in agreement.

I started my career in the electrical utility industry as a lineman helper five years before President Richard Nixon signed into law the Williams-Steiger Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. It became enforceable in late April 1971.

At that time, I was just beginning my apprenticeship as I was too young to be a lineman in the mid-1960s and Uncle Sam had some other ideas for me. Now the federal government was trying to tell me how to do my job? I didn’t like it. This feeling was shared by local management at the utility where I was working.

Today, I suspect if you ask employers who have received citations from OSHA, some of them still have this opinion of the agency. However, a review of history might change some of those opinions – because the truth is, OSHA has played a vital role in ensuring the safety and legal rights of the American worker.

Early History

Following the Civil War, manufacturing was booming in the U.S. There were no federal laws or regulations yet to protect workers. Working conditions could be dangerous, and those on the job were often young, inexperienced and exposed to dust, chemicals, machine hazards and more. A few states tried to enact safety regulations, but they were mostly underfunded and difficult to enforce.

The growth of mass media was one of the major factors that helped the American worker gain on-the-job protection. Ready access to newspapers and magazines made it so the average citizen knew more about current events than ever before. Stories of many worker tragedies – such as the 1907 mine disaster that killed 362 coal miners in West Virginia and the 1911 fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Co. that took the lives of 146 workers – were written and published in various media outlets. These incidents, and likely many others that did not make it into the papers, came years after the 1889-1890 Interstate Commerce Commission’s first publication of accident statistics, which indicated there was a need to improve safety in the railroad industry. It had been clear for some time that people were not always safe in their workplaces.

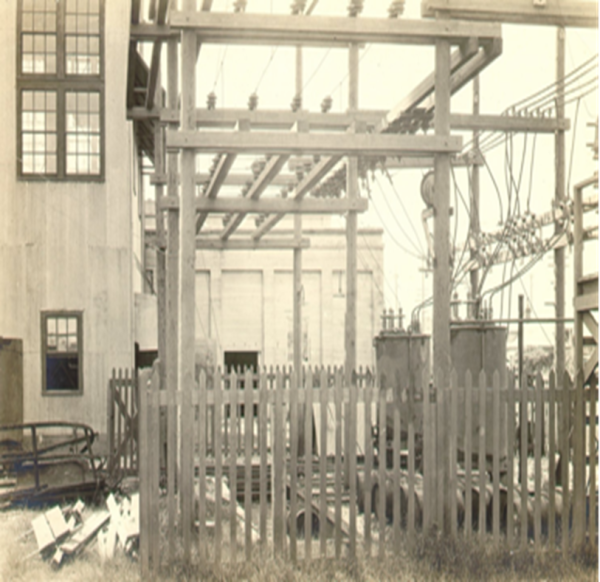

In 1903, the U.S. Bureau of Labor began publishing studies of trades that were unusually hazardous. Mining, logging and electrical work were recognized as hazardous occupations.

In 1908, under President Theodore Roosevelt, Congress passed a limited workers’ compensation law for federal employees. This law applied to employees of interstate railroads and railroad workers who were employed in the District of Columbia or a U.S. territory. A railroad that fell under the law was “… liable in damages to any person suffering injury while he is employed by such carrier in such commerce, or, in case of the death of such employee, to his or her personal representative, for such injury or death resulting in whole or in part from the negligence of any of the officers, agents, or employees of such carrier, or by reason of any defect or insufficiency, due to its negligence, in its cars, engines, appliances, machinery, track, roadbed, works, boats, wharves, or other equipment.”

The 1910s to the 1930s

States followed suit in their efforts to provide compensation to injured workers of all trades. However, a loophole existed under British common law, which was still in effect in the U.S. at the time. The bottom line was that the burden of proof was on the worker to prove their employer was negligent before the company had to provide compensation.

The bill establishing the U.S. Department of Labor was signed March 4, 1913, by President William Howard Taft. The department’s primary function at that time was to improve unemployment and “to foster, promote and develop the welfare of working people, to improve their working conditions, and to enhance their opportunities for profitable employment.”

In that same year, several companies worked together to found the National Safety Council and began to pool information on workplace incidents. The National Electrical Safety Code was founded in 1913 as well. The purpose of the NESC was to provide standards for construction and strength of materials. Government agencies, such as the U.S. Bureau of Mines and the National Bureau of Standards (known today as the National Institute of Standards and Technology), provided support while universities also researched safety problems for firms and industries. Still, very few enforceable regulations provided relief to the American worker.

With the U.S. entry into World War I in 1917, adequate war production became a national necessity, and labor questions (i.e., who would do the work of the men called to duty) assumed paramount importance.

Women entered manufacturing jobs in large numbers during the war to replace the men who had gone off to fight. Many of the jobs that women performed were dangerous, but the work got done, demonstrating to Americans that women could fill the same jobs as men and were willing to take the same risks. Again, however, there was little effort to improve the safety of these wartime jobs.

The Great Depression of 1929 caused widespread unemployment across the country. In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced the New Deal, a federally funded program to stimulate jobs and the economy. While it did little to improve safety in the workplace, a byproduct of the New Deal was the development of electric power. The Tennessee Valley Authority was established in 1933 to cover a seven-state area and supply inexpensive electricity and flood control. This was a big boost for the industry and moved forward the electrification of America to include rural areas.

Two years later, the National Labor Relations Act, also known as the Wagner Act, created the National Labor Relations Board to supervise union elections and help prevent businesses from treating their workers unfairly.

World War II to the 1970s

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, prompting the U.S. to enter World War II. The war effort stimulated American industry, effectively ending the Great Depression. But the increase in jobs due to wartime needs still did not improve safety conditions in the workplace, even though the National Labor Relations Act had been in effect for several years.

In the aftermath of World War II, the U.S. enjoyed a period of economic growth that improved the standard of living for most Americans. However, with the creation of middle-American suburbia and a car in every garage, the emphasis was on job growth. At that time, that was enough, and there continued to be little effort made to improve the safety of the workforce.

In 1968, the U.S. Secretary of Labor, W. Willard Wirtz, led a series of hearings and cited two casualty lists facing America at that time: the military toll in Vietnam and the industrial toll at home. Wirtz claimed that three out of four teenagers entering the workforce would likely suffer at least one minor disabling injury during their career. Some labor protection laws were then passed in 1969 under President Lyndon B. Johnson, but these individual laws were nowhere near as comprehensive as OSHA laws would eventually be.

OSHA’s Legacy

It is chilling to note that in 1970, an estimated 14,000 workers lost their lives on the job, which averages out to about 38 workers dying at work each day that year. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics recently published their latest official numbers for the year 2019. The agency reported that 5,333 people lost their lives on the job over the course of that year. This is more than a 62% decrease in just the number of fatalities from 1970. It’s important to note that during that same 40-year timespan, the American workforce doubled.

The total recordable incident rate (TRIR) is a more accurate measure based on hours worked. It is measured in 100 employees working one year or 200,000 hours and is a measure of all accidents and illnesses, not just fatalities. TRIR allows for comparison between large and small companies and better illustrates the improvements made after the formation of OSHA. For instance, in 1973, the TRIR was 11. By 2019, it had been reduced to 2.8 – a massive improvement.

Like anything worth doing, it has taken time, talent and treasure to make workplace safety and compensation a given for everyone who has a job. An evolution of laws and the throwing off of generations of beliefs about what is just have led to the improved safety of today’s American worker. It is easy to see that a great deal of time and attitudinal change were necessary to reduce the number of people being seriously injured or killed in their quest to provide for their families. The electrical industry had a mortality rate of one in two persons in its early days. Today, one in 2,000 people die because of work injuries in the electricity service sector. While we must continue working to whittle that number down to zero, we can also be proud of how laws have resulted in saving lives.

In closing, anyone who has entered the U.S. workforce within the last 50 years has always worked under the protection of OSHA. So, while the agency might sometimes make it difficult for businesses to do business, it’s worth it for the safety and livelihood of our workforce.

About the Author: Rayford “RL” Grubbs, CUSP, is a health and safety manager for Think Power Solutions (www.thinkpowersolutions.com).