The Biological Basis of Complacency

The adverse effects of complacency in the workplace have long been an ongoing source of concern in the safety community. What is not agreed upon is the reason for this problem. In my own experience, I have noticed that safety professionals use the term “complacency” in different ways to refer to different kinds of events.

The ability to address and solve a problem is greatly increased when the problem is properly understood, so I embarked upon a research effort to better understand this hazard. As a result, I produced a paper that explores a previously undiscussed component of complacency: basic brain design. Given how the human brain has evolved to operate, I argue that complacency is an unavoidable risk factor that can be managed but not eliminated. With this scientifically based understanding of complacency, safety professionals can more effectively prevent complacency from posing a risk to their employees’ safety.

The Symptoms of Complacency

Complacency is not an easily observable condition, and objective criteria can be elusive. Based on interviews with safety professionals, I compiled a list of anecdotal clues these professionals use to gauge the presence of complacency:

- Working too fast or too slowly.

- Eyes not on task.

- Occupying space in the “line of fire” or danger zone.

- Multitasking (e.g., having conversations while working).

- Not taking risks seriously (e.g., goofing off or bragging).

- Not following procedures (e.g., using a two-handed tool with one hand).

- Not completing checklists, or pencil-whipping them.

- Skipping basic PPE or safety requirements.

- An increase in incidents without easily identifiable root causes.

- The frequency of rework incidents.

- Decreasing frequency of near-miss or good-catch reports.

The traditional approach to combating complacency, based on these types of clues, has been to attempt to “fix” employees’ mental and emotional states. Solving complacency is often viewed as needing to bolster employees’ sense of responsibility and attention to detail. Tactics include reminding employees to pay attention and think about what they’re doing and admonishing them to slow down. However, refusing to tolerate shortcuts or wishing that employees cared more about their work is not the answer.

More critically, I argue that these external expressions are symptoms of complacency that are driven by a biological root. Targeting the symptoms of complacency will not eliminate this hazard. Effectively tackling it requires targeting the root cause – and targeting the root cause requires an understanding of how the brain handles repetitive behavior.

The Neuroscience of Habit

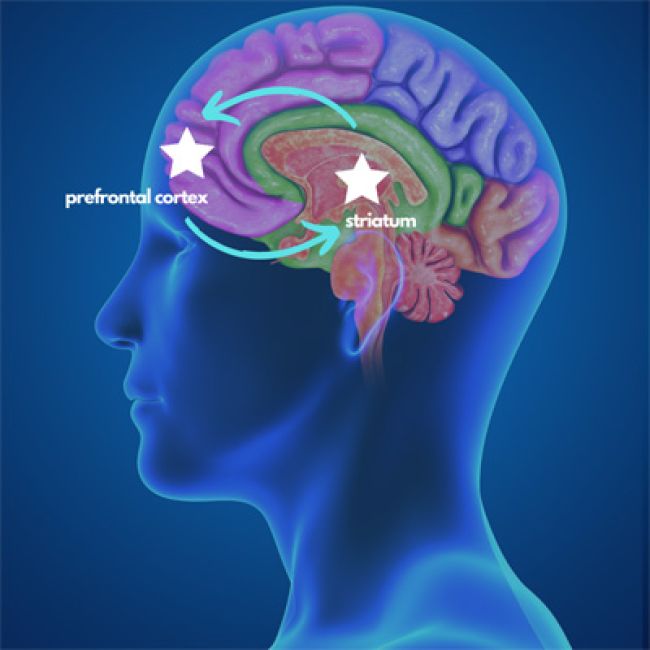

Typically, when someone performs a behavior or action for the first time, their prefrontal cortex (PFC) fires and communicates with their striatum. The PFC is the part of the brain that sits above the eyeballs and is involved in many of our executive functions. Looking at the list of activities assisted by the PFC reveals a wish list of employee behavior, like planning, making decisions and anticipating consequences. The striatum is the habit-, reward- and goal-motivated behavior center and has been described as the learning machine part of the brain.

When the brain is doing something new, it is a lot of work, and all the neurons fire along the path between the PFC and the striatum. However, the brain is a quick learner. The next time it repeats that action, it’s a little more familiar, so fewer neurons fire. As this process is repeated, the action gets easier and easier, and fewer and fewer neurons fire. When something is a habit, the PFC does not need to be involved, and not all the neurons fire during this activity – just the ones at the beginning and the end.

There are two points from neurobiological studies and academic literature that are key to managing the risk of complacency in the workplace: (1) Once habits are created, the sequencing moves to a different part of the brain, and (2) when a behavior or action has been repeated often enough to become a habit, the PFC no longer needs to be involved to successfully complete it.

Simply stated, repetition is the mother of habit. By repeating an action over and over, a person carves a neural pathway deep in the brain that requires very little energy or effort to run.

The Value of Habits

Every second, the brain must process an unquantifiable amount of information. This includes everything from our own autonomic nervous systems (internal temperature, heart rate, eye blinking and more) to taking in external stimuli (including colors, shapes, locations and movement) to just doing our jobs.

With this plethora of information to process, the brain needs to rely on shortcuts. There are many different types of shortcuts, but habit is the one applicable to our topic here. A habit is a neurological shortcut the brain can use when engaged in a repetitive task. The range of repetitive tasks is quite large. Not only does it include actions like brushing your teeth and donning PPE, but also behaviors like asking for help, reacting calmly in stressful situations and solving problems. Beyond behaviors, people have created habits to process emotions, thoughts, decisions and actions.

Habits are an impressive productivity tool for the brain. They allow people to perform tasks more reliably and more quickly. Habitual behaviors also free up more cognition space in the brain, allowing us to multitask and tackle more demanding undertakings. Essentially, habits free up our brain to do other things and can give us a competitive advantage.

Even if productivity were not the goal, our brains would employ habits because it’s easier and relieves the cognitive toll of so much information flooding our brain throughout the course of our daily lives. In rather unscientific terminology, the bottom line is that the brain is essentially lazy, and it does not want to fire up the PFC if it doesn’t have to or for any longer than it needs to.

The Downside of Habits

But there is a price exacted when habits are triggered: the PFC is often no longer actively involved in brain processing. When the PFC is not engaging, then we have lost an important safety resource. Habits are a double-edged sword. They are essential for executing many safety protocols, but they also cause us to lose another tool in our safety kit: robust PFC activity. As a result, people can be less aware of what’s going on around them.

A New Definition of Complacency

Based on this understanding of the biological process of the human brain, I want to offer a more accurate definition of complacency – one that also opens the door to solving the problem in a way that doesn’t blame people for being human. Complacency is a state of decreased external awareness and reduced sensitivity to hazards caused by the brain’s ability to activate neural pathways that require less PFC activity.

This definition reflects the current neurobiological assessment of what happens in the brain when habits are established. Most importantly, this definition of complacency reflects that complacency is an internal state, not one that is easily observable. In fact, for all practical purposes, it is impossible to identify complacency externally.

By looking at indicators like working too fast or slowly, eyes not on task and having conversations while working, safety professionals are looking for external clues to an internal state. Unfortunately, complacency cannot be resolved by focusing on these outer symptoms because even if the safety professional successfully removed all outward expressions, there is still no guarantee that the employee’s mind is actually engaged in the task at hand. To offer a real-world, personal example of this dynamic, I am chagrined to admit that I can be looking at my husband, nodding my head and still not be listening to what he is saying.

Managing Complacency

Accepting the biologically driven nature of complacency not only eliminates the stigma of complacency, but it also creates a path for managing – not eliminating – this hazard. Complacency is never a hazard that you can check off your list because it will never go away. Every human being’s brain will be inclined to rest in habit mode and avoid activating its executive functions whenever possible. Safety professionals can use the brain’s natural tendency to employ neural shortcuts to their advantage and must strategically plan to re-engage the PFC when complacency is a disadvantage.

Across the board, safety professionals want their employees to have maximum cognitive function available for working safely, so that means streamlining forms, eliminating unnecessary steps, and providing access to physical and mental health resources. In addition, safety professionals can use repetition to their advantage by practicing key behaviors until they become deeply ingrained in the brain. Finally, occupational safety and health professionals should strategically prompt their employees to re-engage the PFC at key points, especially when an employee is about to execute an unrecoverable step.

Conclusion

Complacency is a byproduct of habit – of being able to operate out of the striatum and avoid the executive functions of the PFC. Complacency is not a conscious choice or moral failing. It’s how the brain is designed. The better the brain can become at moving behaviors to habit level, the more efficient it can be with its limited resources.

Most of the time, complacency works in your employees’ favor and increases their productivity, but when it poses a safety concern, effectively tackling complacency means re-engaging the PFC. The more cognitively engaged employees are, the safer they will be. Because the drive toward complacency is relentless, safety professionals should accept that helping employees avoid this hazard is a constant process of strategically re-engaging the PFC, surprising employees and triggering their awareness.

Finally, you can download the full report I referenced at the beginning of this article at https://habitmasteryconsulting.com/complacency-report. It shares the results of surveys and interviews about the scope of complacency within organizations and offers more strategies to guide safety professionals’ efforts in tackling this hazard.

About the Author: Sharon Lipinski is the Habit SuperHero and CEO of Habit Mastery Consulting (https://habitmasteryconsulting.com), which helps organizations increase their targeted safety behavior by up to 150%. She is a Certified Gamification for Training developer, certified CBT for insomnia instructor, speaker, TV personality and coach dedicated to helping people create the right habits so they can be happier, healthier and safer at home and in their work.