Secondary FR Garments: Practical Solutions for Protection

Cleanup of potentially hazardous materials and flammable contaminants can sometimes be a part of an electrical job. When workers arrive on a scene, they cannot always be sure of the exposures or contaminants they will face. In electrical work, it could be oil that contains a small number of PCBs. This oil, and other contaminants, is flammable and can affect the flame-resistant properties of garments until it is washed from the garments. Working around flammable contaminants, as well as flame and thermal hazards like arc flash potentials and flash fire potentials, often requires a PPE safety system that can be difficult to balance. Some workers may need chemical protection, flame protection or both. Secondary protection used in such circumstances, like disposable garments, can create a fast and effective way to decontaminate and clean a scene – by removal and disposal – without soiling or degrading the primary protection underneath. Because of this, disposables often are useful over daily wear. Many workers and managers assume that a chem suit is a chem suit and use the common polyester/polyethylene suits to cover their arc-rated/flame-resistant (AR/FR) gear. This can be a disaster if one of the suits ignites, melts and continues to burn, or if part of the suit becomes molten and melts onto a worker’s hands or face.

In the AR/FR PPE industry, however, disposable garments are few and far between, and the standards aren’t quite in place to help make the distinction between garments that are truly flame resistant in specific hazards versus marketing. The lightweight, thin materials typically can’t pass some of the harsh requirements set forth for garments to be used as primary materials. And even though most are not intended for primary protection, there are limited standards to guide manufacturers on appropriate tests and claims for these types of products. This is especially true for those needing multihazard protection in the outermost disposable garment. There are disposable garments on the market that boast protection from a variety of hazards, like blood-borne pathogens, dry particulates and chemicals. When flame resistance comes into play, there are even fewer options on the market.

How Far Have We Come?

Disposables have come a long way in the past few years, but we are still lacking in standards on the AR/FR side. Initially, polyester spunlace disposable garments were used for chemical protection, and they revolutionized the industry in providing secondary, fast protection that could be doffed and disposed of without concern of contamination of primary clothing; these products add extra protection to the worker at a low cost. Later, coated and sealed-seam garments on the chemical protection side were made to withstand even higher-level exposures, including chemical warfare, an unlikely scenario in the workplace. Disposables for chemical protection worked well for chemical hazards, but they were not adequate or intended for the risks from flash fires or electric arcs. Flame resistance of disposable garments still hadn’t been adequately addressed from a standards perspective, and there were misunderstandings in the market regarding FR PPE, including PPE intended to be disposable.

In 1994, the first AR/FR rainwear was developed. This is when the battle first began to educate users and caution the market about purchasing items only labeled as “FR”; this battle continues today. Flame resistance is defined by NFPA 2113 as the “property of a material whereby combustion is prevented, terminated, or inhibited following the application of a flaming or non-flaming source of ignition, with or without the subsequent removal of the ignition source.” This is a simple definition and the ignition source is not described. Because we cannot say that someone using a plumber’s torch and someone exposed to flash fire need the same level of protection, it’s important to consider not only the term “FR,” but the actual hazards faced, and to check for appropriate standards in labeling. There is no standard to address low-level flame sources like a plumber’s torch. Some label items “FR” or “self-extinguishing” using small-scale methods alone, which is not adequate. By themselves, these small-scale methods cannot properly evaluate the propensity of a material to melt and drip when faced with a large-scale exposure like a flash fire or an electric arc.

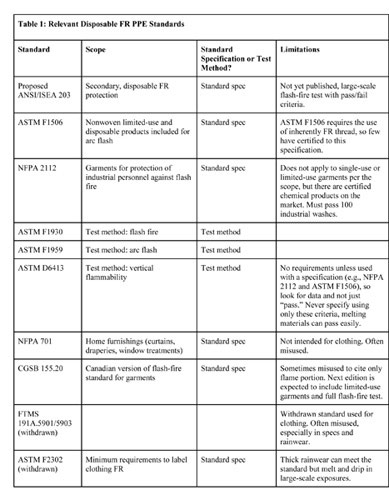

A similar problem exists with chemical-resistant garments and disposables. There are chemical-resistant garments that are flash fire rated (FFR) and/or arc rated, but there also are garments on the market that should not be used in a flame or arc exposure due to the hazards of melting and dripping. How can purchasers tell the difference? Melting materials like polyester, nylon, polyethylene and olefin are not acceptable unless they are present in small portions in a blend, even if the garment is labeled as FR – unless, of course, testing to the proper standards has been demonstrated. In Table 1, we’ve outlined the commonly used standards in the industrial FR clothing industry to demonstrate their uses; we’ve also included limitations to describe instances of misuse.

Today there are more options on the market, but without a published specification to primarily address disposable FR garments, manufacturers have taken it upon themselves to perform due diligence and large-scale testing. The first standard to address FR disposable garments was NFPA 2112, which added the allowance for FR disposable materials as “nonwoven” materials. Some materials had been tested against the standard, but it was very costly. In addition, the standard had some disadvantages to the end user who wanted a disposable garment. The disposable must meet a minimum body burn percentage and other tests that make the nonwoven disposable beneficial in some jobs but less disposable from a cost perspective. Today NFPA 2112 excludes limited-use garments in the scope. CGSB 155.20, the Canadian standard for flash fire that is like NFPA 2112, is expected to include direction for limited-use garments in the next edition.

Table 3 of ASTM F1506 currently includes requirements for nonwoven limited-use and disposable products. Bursting strength, dimensional change (if launderable), vertical flammability to ASTM D6413 and arc testing to ASTM F1959 are all included. However, this document is rarely cited for disposable garments because to comply, garments must be sewn with inherently FR thread, which is unnecessary for a disposable garment and prohibitively raises the cost of the garment. Additionally, NFPA 70E adds a requirement for FR zippers, which is another expense that might double the cost of a disposable garment. Our testing shows that the lightweight zippers on most of these garments fall off as the garment is destroyed.

A new standard, ANSI/ISEA 203, is underway and almost ready for publication. It will be the first to directly address secondary PPE intended for flame and thermal protection. This document was created specifically for disposable secondary garments intended to be worn over primary protection and to provide a limited amount of flame resistance – limited, as these garments are not intended to serve as primary protection and do not have to meet the same requirements as primary protection.

This standard will be a positive release for the industry, as up until now, some were using inappropriate standards or melting materials with one or two small-scale tests to label melting materials as FR. Based on our many years in the industry, we like to educate that it’s not really flame resistance you need to look for on PPE labels; it’s the appropriate standard specification associated with the hazard or hazards you are at risk for. Having ANSI/ISEA 203 as a published document specifically for disposable rainwear is an improvement and a step in the right direction – this will at least set minimum requirements for garment manufacturers to follow. The published document is expected to include small-scale vertical-flame testing and large-scale flash-fire manikin testing. However, it is not expected that melt and drip requirements will be included in the large-scale flash-fire manikin testing, which may mean that some lightweight melting materials could pass the standard, but rainwear – a common melting FR garment – is excluded. There will be afterflame and body burn percentage requirements, and the disposable garments will be tested over primary protection and have a very tightly controlled amount of afterflame, which should limit any dangerous materials.

What Can I Do Now to Ensure Compliance?

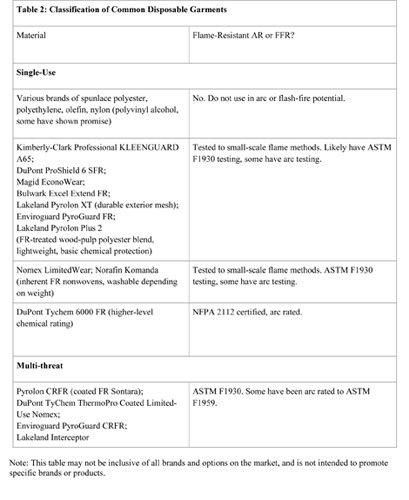

First and foremost, determine which hazards are present and the type of disposable or limited-use clothing that is needed; disposable garments provide warnings to only be used over primary protection. Check the labels for fiber content, care instructions (if limited-use and you need garments that are launderable) and standard compliance. Table 2 is one we commonly use to classify disposable and limited-use materials.

When reviewing test data for secondary disposable or limited-use FR clothing, here are some things to look for:

- Passes common vertical-flammability requirements when using Test Method ASTM D6413 (less than 2-second afterflame, no melting or dripping, and char length shorter than 6 inches). Pretty common, does not indicate a safe product standalone.

- Passes heat-resistance testing (no melting or dripping when tested at 500 degrees Fahrenheit in an oven per ASTM F2894). More commonly indicative of a safe product, but many safe products have issues with this small-scale test.

- No melting or dripping in full-scale tests (arc flash or flash fire). Excellent sign of a quality product.

- Has some protective value from a full-scale test (ASTM F1930 or ASTM F1959).

- Should not melt or drip in your exposure potential.

- Lighter-weight materials may not meet 50 percent body burn or have a high arc rating, but they should be evaluated by a full-scale test method. Other FR clothing should be worn underneath the disposable unless its full-scale rating is adequate for the task.

- Provides garment disposal information and indicates if the garment can be incinerated if the contaminants demand it.

About the Authors: Hugh Hoagland is the founder of e-Hazard (www.e-hazard.com) and an expert on electrical arc testing and safety. He has aided in the development of legislation and standards in the U.S. and globally.

Stacy Klausing, M.S., is quality control manager for the ArcWear textile test lab (www.arcwear.com), which performs testing for NFPA 2112 flash fire and ASTM F1506 arc flash.