Preventing Struck-By Incidents in Utility Construction

Anatomically modern humans emerged over 100,000 years ago. For the bulk of that time, the environment in which we lived didn’t change much or very quickly. Now, think about how much the world has changed in just the last 100 years. One interesting thing to consider is how modern human innovation has continued to overcome innate human deficiencies. We control the environment around us now more than ever, including the way we travel, the way we enjoy the arts, the way we grow our food, the way we care for our sick and injured, and – to bring this point home – the way we protect ourselves.

Today, in our industry, we have access to state-of-the-art training facilities, cutting-edge tools and advanced protective equipment. Our brains, on the other hand, are the same or at least very similar to the brains of the first modern humans. Our ability to take in information about the world around us and make judgments based on that information hasn’t really changed much. Now, overlay that with how the world has changed in the last century, and you can start to see the problem. It’s not that the human brain isn’t a glorious machine capable of incredible things, but it hasn’t had the time to evolve to meet the demands of the modern world. Our brains are currently bombarded with information nearly every second of the day and must filter through all of it to make decisions – sometimes very quickly – that will hopefully result in success instead of failure. It’s also important to note that, over time, the human brain has evolved to take shortcuts, reducing cognitive load to operate in the most energy-efficient way possible. This is where our brain’s greatness gets us into trouble – by taking shortcuts, making decisions based on limited information, misinterpreting the presence or severity of danger, and making assumptions based on previous experiences. This sets the stage for why and how workers continue to get injured or killed by high-energy hazards, even with all of our excellent training facilities, tools and protective equipment.

If not properly eliminated or controlled, high-energy hazards can result in workers being struck by objects, being caught in something or between two or more items, or being in the line of fire when energy is released. And if our brains are pushing us to take shortcuts, misinterpreting risk levels and making assumptions – which they often do – the combination is a potential recipe for disaster.

Some Important Definitions

Before we address prevention methods for these types of incidents, let’s first take a moment to review some important definitions as well as some injury statistics.

“Struck-by” injuries, per OSHA, are “injuries produced by forcible contact or impact between the injured person and an object or piece of equipment.”

“Caught-in” and “caught-between” injuries are defined by OSHA as those injuries “resulting from a person being squeezed, caught, crushed, pinched, or compressed between two or more objects, or between parts of an object. This includes individuals who get caught or crushed in operating equipment, between other mashing objects, between a moving and stationary object, or between two or more moving objects.”

OSHA Severe Injury Reports

The severe injury reports produced by OSHA (see www.osha.gov/severeinjury) provide an opportunity to analyze the occurrence of serious injuries, what caused them and how severe they were. In 2021, line-of-fire injuries accounted for 33% of all event types resulting in serious injury on construction sites. Although struck-by injuries represent the majority, a third of all line-of-fire injuries can be attributed to caught-in and caught-between events.

Here are some examples of severe injuries:

- An employee was operating a scissor lift when their finger got caught between an electrical panel and the lift’s railing, resulting in a fingertip amputation.

- An employee was walking under an aerial lift when they were struck by a box full of materials that fell from the lift, resulting in a concussion and brain bleeding.

- While flagging traffic, an employee was struck by a falling utility pole. The employee suffered a broken ankle.

Hazard Management

So, how do we effectively manage these types of hazards? Consider the following four-step process.

Step 1: Anticipate the Hazard

When discussing how to control hazards, we tend to start with hazard identification on the job site. Perhaps a better approach is to start by anticipating hazards in advance of the work. If you can plan for the types of typical hazards that develop during certain tasks, you can take preemptive measures to remove or control them.

Step 2: Identify the Hazard

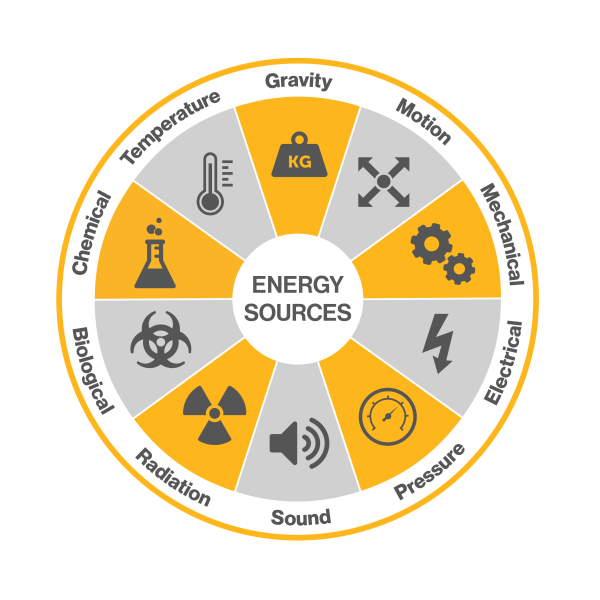

Identifying the hazard or hazards is arguably the most important part of the hazard assessment. This is where your team has a chance to seek out line-of-fire hazards wherever they may be hiding. The energy wheel is a great tool that can be used to identify high-energy hazards of various types; examples include gravity, chemical, electrical and mechanical. If you don’t identify high-energy hazards, that means they will not be controlled, and the crew misses an opportunity to protect themselves. Keep in mind that not all high-energy hazards will be present at the start of a job; many develop during work as conditions change.

Step 3: Eliminate the Hazard

The best course of action is to eliminate hazards when possible. There are varying degrees of protection afforded to the worker through different levels of effective safety controls. Removing the hazard is job one, but that is not always possible.

Step 4: Control the Hazard

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s hierarchy of controls tells us that if hazards cannot be eliminated, workers must apply a series of controls based on availability and effectiveness. The ideal result is one in which risk is dramatically decreased using engineering, substitution and administrative controls. Essentially, the worker reduces risk to the greatest extent possible. If a hazard still exists, the worker must be protected with suitable PPE as a final level of defense. Properly selected PPE that is suited to the hazard and worn by trained, knowledgeable workers will offer protection, but it is still not nearly as effective as elimination or substitution. Good planning before and during the job, plus a review after the job, can help prevent line-of-fire injuries. Allow time to discuss the job, identify high-energy hazards, and select the proper tooling and equipment to control them. Discuss what went right and what can be improved upon after the job.

Conclusion

The world around us is complex – and so is the human brain; it’s a marvel that is responsible for an incredible amount of innovation. It’s also purpose built for a previous world. Today, our brains need some assistance. They require time to evaluate complex environments and conditions, help to overcome cognitive biases, and input from others to establish collective understanding. There are tools and techniques available that can help us overcome these issues. We must develop our workers to anticipate, identify and control risk, and to have the discipline to stop work until unsafe conditions are corrected. Show workers how to leverage tools such as the energy wheel during hazard assessments and job briefings. Train them to select the proper safety controls based on risk level, and ensure they know PPE is their last line of defense, with elimination being the ultimate goal. Teach them to build extra margins or capacity into their job plans. A little extra time, space and communication will go a long way in protecting our workers from unexpected human errors and equipment failures. Finally, become personally involved in training, coaching and field evaluations. Together, we can reduce the number of injuries and fatalities related to high-energy hazards.

About the Author: Mike Starner, CUSP, CHST, has 30 years of experience in the electric utility industry and currently serves as the executive director of outside line safety for the National Electrical Contractors Association.

- June-July 2023 Q&A

- The Art of Safety: Protect the Worker

- Overcoming the Illusion of Safety

- Lineworkers and Rubber Sleeves

- The Quail Effect: An Indicator of Safety Culture

- Preventing Struck-By Incidents in Utility Construction

- Strengthening the Substation Fence

- Training Users of Aerial Lifts