Assessing and Mitigating Risk in Helicopter Line Work

Considered a high-risk activity, aerial line work can be performed safely using various tools, processes and procedures.

Aerial line work using helicopters is a proven method utilized in our industry to perform certain tasks safely and efficiently. Helicopters have supported the utility industry since 1947. Operators conducting aerial work in support of the utility industry encounter different hazards due to various flight profiles, terrain, infrastructure and weather environments. Aerial work concerning the utility industry exposes aircraft and operators to the same hazards of any aircraft that operates at low altitudes and slow speeds. The first step of a safety system approach to mitigating risk is to define the operational environment and outline the hazards associated with each flight profile.

Aerial line work using helicopters is a proven method utilized in our industry to perform certain tasks safely and efficiently. Helicopters have supported the utility industry since 1947. Operators conducting aerial work in support of the utility industry encounter different hazards due to various flight profiles, terrain, infrastructure and weather environments. Aerial work concerning the utility industry exposes aircraft and operators to the same hazards of any aircraft that operates at low altitudes and slow speeds. The first step of a safety system approach to mitigating risk is to define the operational environment and outline the hazards associated with each flight profile.

Risk Assessment Tools and Procedures

Line work and flying a helicopter are both considered to be inherently high-risk activities, so combining them into one task may lead you to believe that task is extremely risky, but it can be done safely by identifying and mitigating the risks. Industry tools and procedures that we use for identification and mitigation include risk assessments, safe work procedures, safety management systems, tailboards and reconnaissance flights.

Every job must begin with a risk assessment to be completed by Operations as they understand what methods will be used. Your safety team should be an active participant in the process. The initial risk assessment is done before the job begins. Once that assessment is complete, Operations and Safety work together to mitigate risks.

Every job must begin with a risk assessment to be completed by Operations as they understand what methods will be used. Your safety team should be an active participant in the process. The initial risk assessment is done before the job begins. Once that assessment is complete, Operations and Safety work together to mitigate risks.

Safe work procedures, or SWPs, are another tool used to minimize risks. SWPs are step-by-step instructions on how to perform a particular task. The order of the steps matters, and no step can be skipped. During the morning tailboard, discuss the SWPs to be used. Ensure everyone understands what they will be doing and the steps to follow to accomplish the task.

If changes are needed to an SWP due to system configurations, customer requirements or limitations with maintaining minimum approach distances, employees shall stop work and regroup. The procedure must be modified by the foreman, pilot and crew members and then sent to management – which includes the chief pilot, operations director and safety director, at a minimum – for approval. This process, instrumental in the success of aerial operations, can be done smoothly and with minimal time delays.

The safety management system (SMS) is a coordinated, comprehensive set of processes designed to direct and control resources to optimally manage safety. In an SMS, unrelated processes are built into one combined structure to achieve a higher level of safety performance, making safety management an integral part of overall risk management. An SMS is based on leadership and accountability. It requires proactive hazard identification, risk management, information control, auditing and training. It also includes incident and accident investigation and analysis. Formal training is required for the safety director and other personnel involved in these processes.

The safety management system (SMS) is a coordinated, comprehensive set of processes designed to direct and control resources to optimally manage safety. In an SMS, unrelated processes are built into one combined structure to achieve a higher level of safety performance, making safety management an integral part of overall risk management. An SMS is based on leadership and accountability. It requires proactive hazard identification, risk management, information control, auditing and training. It also includes incident and accident investigation and analysis. Formal training is required for the safety director and other personnel involved in these processes.

Prior to flight, the pilot performs the flight risk assessment utilizing the Flight Risk Assessment Tool (FRAT). The FRAT is an effective aid in risk awareness and mitigation. The risk assessment focuses on the mission for the day while also considering the environment (e.g., altitude, visibility, winds, terrain), the number of consecutive days the pilot has been on duty and the pilot’s experience.

The FRAT is scored for total risk based on the answers given by the pilot.

- If the total risk score is determined to be low, the pilot is good to go.

- If the total risk score is determined to be elevated, the pilot mitigates the risk factors and is then allowed to fly.

- If the total risk score is determined to be moderate, the pilot shall contact the chief pilot or safety director to discuss the mitigation plan.

- If the total risk score is determined to be high, the pilot shall stop. The flight is not allowed to commence until the risk can be mitigated.

Each day, a tailboard must be completed at the landing zone once the pilot arrives. While the foreman (i.e., the employee in charge as stated by OSHA) is responsible for completing the job safety analysis, the pilot in charge is an integral part of the tailboard and must be an active participant in the process. The tailboard is key to a successful job, and the entire crew must be actively involved.

A reconnaissance flight is conducted each day to look at the lines, structures, and any obstacles or obstructions prior to flying a lineworker. This type of flight – which can be conducted only by the pilot but often includes the foreman or a lineworker – is performed specifically to look for any changes from the day before.

Human External Cargo

Human External Cargo

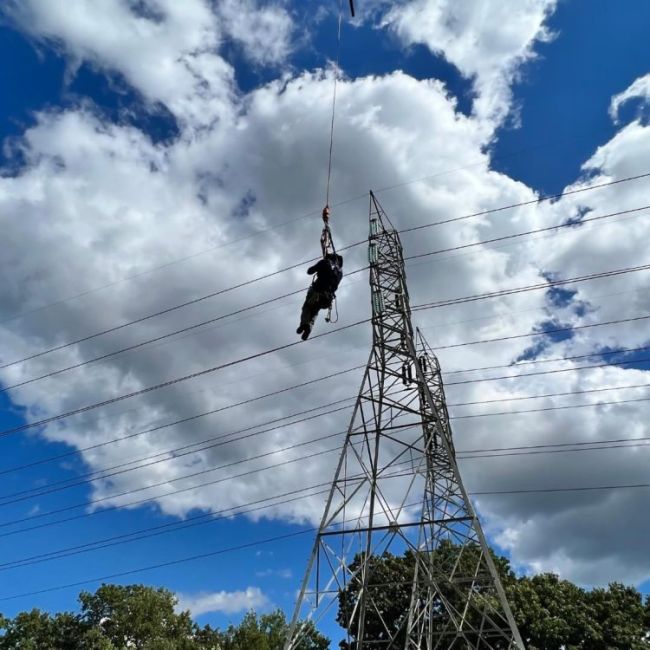

When assessing and mitigating risk in helicopter line work, human external cargo, or HEC, must always be considered. HEC is defined as any worker who is part of the flight crew and is engaged in an activity outside the aircraft.

The FAA has set forth three different classes of HEC operations:

- Class A: skid or platform activities

- Class B: HEC longline activities

- Class C: pulls

In the early 1980s, Class B was adopted and modified by various agencies as well as the utility industry for use in a number of missions and tasks. The regulation, 14 CFR 133.35, “Carriage of persons,” allows a person to be carried during rotorcraft external-load operations when that person:

- Is a flight crew member.

- Is a flight crew member trainee.

- Performs an essential function in connection with the external-load operation.

- Is necessary to accomplish the work activity directly associated with the operation.

Class B HEC has become an essential tool within the power utility industry. Thorough training of both pilots and crew members is critical to safely conducting Class B HEC operations. Some examples of Class B HEC tasks that have proven to be safe and efficient include:

- Marker ball installations.

- Installation or removal of armor rods.

- Installation of travelers.

- Placement of crew members at elevated positions (structures and working platforms).

Lineworkers are often excited to work from an HEC longline. However, it’s critical to ensure their skill level prior to them doing so; this can be verified with specific training and an exam. It’s necessary to have a conversation with each lineworker not only about line work but fall protection, rigging, fueling, landing ladders and so forth. Following the classroom training and exam, each lineworker must be evaluated for proficiency in the field by the foreman, pilot and other crew members.

Note that the pilot is ultimately responsible for the safe conclusion of an external-load operation.

Crew Resource Management

Crew resource management (CRM) is another type of management system important to mention. The purpose of CRM is to make optimal use of all available resources – including equipment, procedures and people – to promote safety and enhance the efficiency of flight operations. CRM is concerned not so much with the technical knowledge and skills required to fly and otherwise operate an aircraft but rather with the cognitive and interpersonal skills needed to manage the flight within an organized aviation system. CRM fosters a climate where the freedom to respectfully question authority is encouraged.

CRM is crucial when conducting patrols. While patrols are an aerial task believed by some to be simple, this is untrue. The pilot and observer must conduct a preflight briefing prior to each patrol to discuss weather, fuel requirements, the patrol route, known or recently identified obstacles, and noise-sensitive areas. The pilot and observer must work as a team.

Aerial work requires effective communication, due diligence to maintain situational awareness, and an understanding that the pilot, observer and/or mission crew are a team and reliant on each other to effectively communicate observed hazards and safety concerns as they are noted.

As we like to say at our company, it takes two to go but only one to say no. It is essential for work to be stopped if even one team member has a concern. Evaluate the situation and determine if safety measures can be instituted to mitigate the hazard or safety concern. Hazards and concerns must be addressed before reinitiating work.

Closing Reminders

Let’s close out this article with some reminders.

- First, remember to always begin the job with a detailed risk assessment. Eliminate any risks you can and mitigate the remaining risks to acceptable levels.

- All crew members must understand their exact role. Be sure to have a thorough job briefing/tailboard at the beginning of the day, and re-brief as necessary when any conditions change.

- Ensure all crew members are fully trained for the tasks they are expected to perform.

- It takes two to go but only one to say no.

In summary, using the tools and practices covered here will help to ensure that aerial line work remains a safe and effective way for your organization to perform line work tasks.

About the Author: Jenn Miller is the director of safety, health and environment at OneSpan Powerline Services (https://onespanpower.com). She has over 30 years of experience in the electric utility and contract power-line construction space.