Mental Preparation for Safer Work

Frontline employees can develop the ‘right stuff’ through training, character development and good habit formation.

Author’s Note: The first part of this five-part series (see https://incident-prevention.com/blog/when-the-system-isnt-enough-how-to-create-personal-motivation-that-saves-lives/) explored the notion of accepting 100% accountability for our safety at work. This article addresses mental preparation to reduce risk of serious injuries and fatalities. Part three will cover spiritual health, with a focus on clarifying and leveraging our own deeply held beliefs.

*****

Combat had endless tests, and one of the worst sins was “chattering” on the radio, which was reserved for essential messages; loose talk showed the wrong stuff. A Navy pilot once yelled, “I’ve got a MiG at zero!” as the enemy locked on his tail. An irritated voice cut in: “Shut up and die like an aviator.”

–Paraphrased from Tom Wolfe’s “The Right Stuff”

Are U.S. Navy pilots really born this way?

Many lineworkers have their own phrase: “He is a good hand.” While understated, it is meant to describe the pinnacle of lineworker excellence. But what is the “right stuff” in our industry? Calm, cool and collected? Competent, stoic and thoughtful? The kind of person who can say, “Houston, we have a problem” without missing a beat? Do we expect a lineworker to perform a thorough job briefing or safety analysis during a heat wave in the same way astronaut Jim Lovell calculated trajectories for Apollo 13’s return inside an overheated space capsule?

Navy pilots aren’t born calm, and lineworkers aren’t born good hands. These are learned behaviors cultivated through training, character development and good habit formation. As such, this article will not provide readers with a single definition of the right stuff. Instead, it will explain the origins of our natural dispositions and how we can evolve into people others trust with their lives.

What You’re Born With vs. What You Build

Since we’re not born ready-made for hazardous work, it is helpful to understand the raw wiring we begin our lives with and the patterns we develop over time.

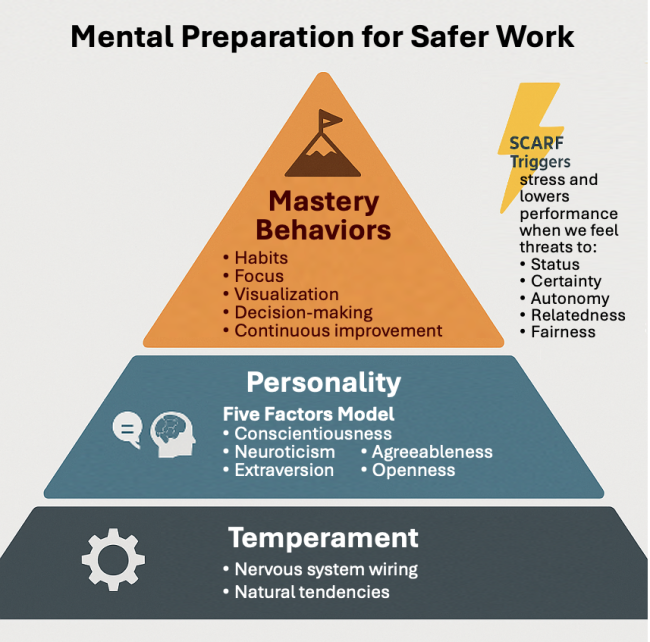

Temperament is your nervous system’s factory setting, the tendencies you exhibited as a toddler and probably still demonstrate today. Some of us are naturally quiet and steady while others jump right into the center of things. None of this is good or bad. It is simply your starting point.

Your personality, or learned response to life, is shaped as your temperament interacts with your environment. You can thank everyone you have ever known for influencing it. Personality is the ongoing negotiation between who you are on the inside and what the external world expects of you. Some struggle with this balance, but most manage it well enough.

Emotional reactions arise from the interplay of both. Like voltage seeking ground, every moment is matched against your temperament and personality. Experiences in line with your natural tendencies generate little emotional current, while those that conflict create spikes. If someone threatens your family, for example, you’ll almost certainly feel it at full wattage; less so if someone hands you a package of peanut M&M’s instead of the plain ones you prefer.

Strong spikes become trigger points that can create havoc. Thankfully, David Rock, Ph.D., devised the SCARF Model, a cheat sheet for understanding these emotional triggers. In simple terms, the typical adult will have an emotional response to a perceived threat against their sense of status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness or fairness. The bigger the threat, the bigger the reaction – works every time. Consider an apprentice who has just been insulted in front of the rest of the crew. Depending on their temperament, they may react loudly and immediately or quietly a few hours later. For some it will be an immediate fistfight; others will prefer nailing your favorite hard hat to a pole when you’re not around.

What Predicts Safe Behavior?

Once you know what sets you off, you can train yourself to manage those triggers and influence safety in the field. Psychologists have studied five core personality traits – measured by the Five Factor Model, which has been supported by numerous studies since 1992 – that predict safety-related behavior. Taking this assessment can help you understand your temperament, personality, emotional triggers and how likely you are to work safely in hazardous conditions. The five factors are:

- Conscientiousness: High assessment scores indicate deliberate, careful work. Low scores suggest carelessness.

- Neuroticism: High scores signify impulsive, reactive behavior, especially under stress. Low scores mean stability, calm and steady decision-making.

- Extroversion: High extroversion can either lead to distraction and horseplay or, with genuine competence, turn into strong, vocal advocacy for safety.

- Agreeableness: High scores mean you’re cooperative, willing to follow rules and a team player.

- Openness: Being open to untested approaches in hazardous situations can be risky, but being cautiously open to new safety tools and methods is a plus.

It is in your best interest to know your Five Factor scores, which highlight natural risks and areas that may need development. Although personality does not dictate your decisions, it does strongly influence your likeliest choices, and most of us are more predictable than we realize. Five Factor assessment results often confirm an individual’s suitability for line work, but even then, understanding these traits provides clearer insights into how we operate internally.

Personality Can Change With Practice

Now that we know which traits influence safe behavior, the question is, can we modify our own personal traits to enhance our safety in the field? Contrary to popular belief, the answer is yes – but there are three requirements: (1) willingness to change your behavior, (2) belief that you can change and (3) consistent practice until the new behavior becomes habit.

This may sound like psychobabble, but it is based on the same principle as boot camp, during which character development trains emotions. Boot camp attendees typically walk in with one disposition and walk out with another. Line apprenticeships work the same way. Often, there is a notion that we rise to the occasion, but the reality is that we sink to our level of training. True mastery is on us. It is – and can only be – a personal choice.

Elite athletes and special operations soldiers are prime examples. Their careers demand constant mastery, so they relentlessly concentrate on how they eat, move, sleep, communicate, focus, make decisions, plan their work and avoid complacency. Their apprenticeship never really ends.

In the utility world, effort often tapers once someone tops out, but we shouldn’t give up once we’ve “made it” because injuries and fatalities still happen. True mastery doesn’t stop at the peak; it’s up to each of us to keep learning and improving. Full accountability for our own safety means we shouldn’t ignore anything that could give us an edge.

Upgrading Your Mental Firmware

If your temperament is the factory setting of your nervous system, then mastery comes from upgrading the mental firmware that runs on top of it. The first step is understanding how you’re built (i.e., your natural temperament and the personality you’ve developed over time). The next step is intentionally improving how you operate.

This is when models like SCARF become useful. In addition to explaining why you react the way you do, they also help you predict what will set you off, enabling you to manage your pressure points before they manage you.

Note: Because this work is deeply personal, these upgrades should always be voluntary and confidential.

Here are the four steps I train clients to use when upgrading their mental firmware:

- Understand how thinking and emotion interact: Recognize what high-quality decisions look and feel like, especially under pressure.

- Strengthen habits: Build routines that make safe behavior automatic, not optional.

- Improve attention and focus: Stay mentally present and resist complacency.

- Visualize work processes before the day begins: Perform a mental pre-mortem – picture the job, identify hazards and make adjustments – before stepping onto the site.

All of these skills can be trained on, practiced and improved. In combination, they help to close the gap between who a person is naturally and the person the work requires them to be to keep themselves safe.

A Deliberate Endeavor

The right stuff isn’t magic or something bestowed upon you. It’s developed deliberately over time by people who want to be the best at what they do and go home whole. Everyone employed in a hazardous trade has the capacity to develop the right stuff, but it will only happen when workers learn who they are, understand their triggers and commit to mastery.

About the Author: Tom Cohenno, Ed.D., CSP, CUSP, NBC-HWC, is a recognized safety expert and principal of Applied Learning Science (https://appliedlearningscience.com). With deep academic and operational experience as a U.S. Navy veteran, substation chief and former utility executive, he blends real-world insight with evidence-based research to deliver practical, impactful safety solutions.

*****

To learn more about Dr. David Rock’s SCARF model, read “SCARF: A Brain-Based Model for Collaborating With and Influencing Others” (see https://schoolguide.casel.org/uploads/sites/2/2018/12/SCARF-NeuroleadershipArticle.pdf) and “Managing With the Brain in Mind” (see https://davidrock.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/ManagingWBrainInMind.pdf).