Beyond Behavior-Based Safety: Why Traditional Safety Practices are No Longer Enough

To achieve the next step change in safety, we must ultimately change how employees feel about at-risk behaviors.

Traditional safety management practices are built on the assumption that human behavior is rational and occurs primarily through conscious decision-making. Nothing could be further from the truth. We are, in fact, irrational by nature, creatures of habit and deeply influenced by past experiences. To create the next step change in the practice of occupational safety, we must revisit existing paradigms defining it, revise them to better align with research emerging from advancements in neuroscience, and adapt to practice realigned strategies of an affective nature.

Irrational by Nature

In 2016, a municipality in western Virginia experienced a fatality when a maintenance worker entered a confined space containing lethal atmospheric conditions. The victim, a father of two young children, entered an underground vault to take a pipe measurement. As the final investigation revealed, and for reasons unknown, the victim chose not to initiate a permit required for the entry and did not test the space for atmospheric conditions prior to entering it.

By all accounts, this tragic event should never have happened. Less than one month prior to his death, the employee had taken and completed a very thorough confined space training course. Not only had he demonstrated understanding of the content and material, but he also mastered it, scoring 100% on the test. The individual involved was regarded as a great employee and was well-respected by his supervisors and peers alike. He was fully aware of the potential hazards associated with confined space entry and the precautions necessary for the work he was performing. In addition, he was experienced in performing the tasks he had been assigned and had readily available the tools and equipment needed to identify the hazards inside the space that ultimately claimed his life. While all the ingredients for a successful outcome were in place, one critical decision set into motion a spiraling set of circumstances with grave consequences.

This scenario, in one form or another, repeats itself all too often. Employees routinely engage in seemingly mindless behaviors that in retrospect tend to defy all logic and reason, as was the case with the referenced victim. He clearly understood the requirements and necessary precautions for entering a permit-required confined space. And yet it wasn’t enough.

Driven by Feelings

One of the most profound achievements occurring over the past 50 years involves a greatly improved understanding of tendencies in human behavior. Made possible through advancements in brain imaging, neuroscientists can now explain through quantifiable and objective data the primary basis of real-time decision-making. Their findings? Most decisions and subsequent actions are largely emotional, not logical.

The implications of this discovery have profoundly impacted consumer marketing. A growing number of products and services are advertised with the intent of reaching the heart, not the head. A classic example involves marketing efforts for prescription medications. A recent study found that approximately 95% of direct-to-consumer (DTC) ads use emotional appeals (see https://harbert.auburn.edu/binaries/documents/center-for-ethical-organizational-cultures/debate_issues/direct-to-consumer.pdf). How effective are they? Medications involved in DTC campaigns are prescribed nine times more frequently than those that are not. This application of science to market and sell prescription drugs to consumers is so effective, it’s banned in all but two countries around the globe – the United States and New Zealand.

The same body of research used to grow sales can be used to improve workplace safety. Whereas historical approaches have focused on sharing information to convey knowledge, the real opportunity for significant improvement involves shifting perspectives. It doesn’t involve more rules or procedures or additional hours of training in a chalk-and-talk classroom setting. To achieve the next step change in safety, we must connect with employees on an emotional level and ultimately change how they feel about at-risk behaviors.

Most Often on Autopilot

Another significant advancement emerging from behavioral research in the recent past involves a dual process theory. In short, this theory accounts for our ability to process thoughts and information in two fundamentally very different ways. One occurs subconsciously and is characterized as being implicit and automatic. The other occurs consciously and is characterized as being explicit and controlled.

The implications of this collective and growing body of research are monumental to the practice of safety. Whereas we’ve failed to fully recognize the role of emotions in decision-making, we’ve also missed the mark regarding the degree of conscious awareness associated with most behaviors. In reality, we operate on autopilot far more than we may realize and are fully aware of only a very small percentage of what’s going on around us at any given point in time (see www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-brains-autopilot-mechanism-steers-consciousness/).

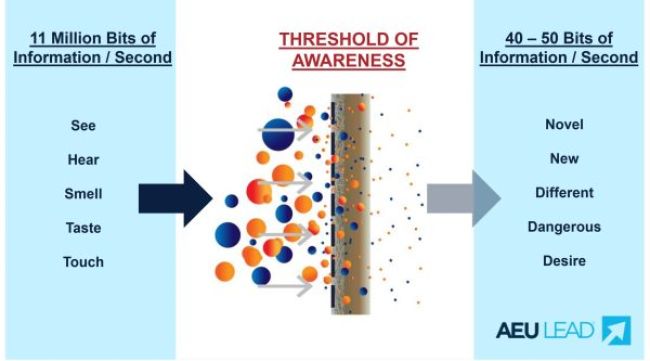

To put this into some sort of perspective, we must recognize both the capacity and limitations of our ability to process information. The human brain can process up to 11 million bits of information every second. Our conscious mind, however, can handle only 40 to 50 bits of information a second (see www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/14681360500487470). The passthrough or filtration of information that’s elevated to conscious awareness is refined over time through experience and is limited to those things that are novel, new, different or perceived as significant.

While the subconscious is largely responsible for the survival of the human species, it’s also to blame for shortcuts, at-risk behaviors and bad habits formed over time. Employees engage in at-risk behaviors when there’s an anticipated gain that outweighs any perceived cost or consequence. When they take a chance for a benefit that’s realized, the behavior is intrinsically reinforced. In addition, the likelihood of recurrence increases and the level of conscious awareness in doing so decreases. This slippery slope is the basis of many unfortunate events and a primary reason why emergency rooms don’t require appointments.

Given the intuitive nature of human decision-making and the prominence of the subconscious in behaviors, occupational safety must evolve to move forward. While past practices have served us well, they’re not capable of creating the wholesale shift in performance needed and now possible.

Intrinsically Motivated

The tenets of behavior-based safety (BBS) vary but can most often be distilled into three key elements. One, organizations must effectively set and convey expectations regarding workplace behaviors. Two, they must implement a means of conducting routine observations to ensure compliance with standardized work practices. And three, they must engage with employees to reinforce or modify behaviors based on observation results.

Deeply rooted in behaviorism, a branch of psychology associated with B.F. Skinner and dating back to the early 1900s, BBS relies on external (or extrinsic) reinforcement. Whether originating from a supervisor, co-worker or safety resource, the mechanism for behavioral change (or conditioning) hinges on feedback. As it turns out, this is an often overlooked and greatly misunderstood area of the science behind BBS that consequently limits its effectiveness as a safety management practice.

As part of the research conducted by Skinner, the schedule of reinforcement is an important consideration in terms of behavior modification (see www.verywellmind.com/what-is-a-schedule-of-reinforcement-2794864). This presents a genuine and seemingly insurmountable challenge for many organizations. When at-risk behaviors occur without consistent or uniform feedback, the effectiveness of the process is greatly reduced. Furthermore, the immediacy with which this process takes place is also highly important. The most effective application of feedback is immediately following the occurrence of the behavior itself. When employees realize anticipated benefits associated with shortcuts and chances taken, the behavior is reinforced internally through actual experience. This, in part, helps explain why words and data have limited effects on behaviors. Labeling a behavior as unsafe, when it may have been performed hundreds or even thousands of times before without negative consequence, is more than a challenge. Furthermore, if the behavior was associated with a forecasted benefit that was realized, you are now at odds with actual experience, a hurdle that logic and reason alone will have limited abilities to overcome.

Subject to Persuasion

The next frontier in safety is leadership-dependent and influence-oriented. It’s about reaching and connecting with employees on an emotional level. It requires shifting how employees feel about at-risk behaviors, as much as or perhaps more so than trying to change what they may think about them. In practice, this requires increasing perceived levels of risk and/or decreasing anticipated gains associated with at-risk behaviors. Developing skills in frontline leadership for those routinely interacting with employees is the key to moving forward. It’s also a critical first step for those wanting to move beyond traditional safety management practices and plateaued performance levels.

About the Author: Joseph White is the director of AEU LEAD (www.aeulead.com), a management development company specializing in the specific needs of frontline supervisors. He has more than 30 years of operational safety experience, the majority of which was with DuPont, where he led a task team assembled to develop the next generation of safety practices using advancements in neuroscience as a foundational basis.