Field-Level Hazard Recognition Training That Works

As a safety professional or operations leader in your organization, one of your primary responsibilities is to ensure your employees can and do complete their work safely. People don’t want to get hurt and you don’t want them to. With that as a given, the question then becomes, how do you accomplish this? You can’t be everywhere watching everything all the time. You can’t point out every hazard on every job site for every worker. So, how do you rest easy in the belief that your employees are recognizing and mitigating hazards and working as safely as possible when you are not around?

I’m going to assume – not always a wise choice, but I’m comfortable with it in this case – that if you are reading this article, you have a system in place for conducting pre-job briefings to discuss the known and expected hazards on your jobs. That is standard procedure in the utility industry. And since many of the jobs utility workers perform each day are very similar, these job briefings can become mundane and lifeless. A briefing becomes a rote process that is almost copy-and-paste from work site to work site. The danger in this is the complacency it can breed. The examination of the job site and the communication and mutual discussion of the hazards present are meant to be the primary preparation for safely completing the assigned tasks. If the process becomes mundane, what are the chances that some of the hazards – especially ones that aren’t typical of the work – will go undiscovered until it’s too late?

It was with this in mind that, about nine or 10 years ago, a colleague of mine and I developed a hazard recognition process and training module designed to heighten awareness, strengthen understanding of the logic behind hazard identification, and equip our workers to better be able to perform high-value, highly effective hazard recognition examinations of job sites. Our audience at the time we developed the program was the workers and supervisors in a coal-fired power plant. Since that time I have used it to train lineworkers with distribution and transmission contractors and even pipeline construction workers. Appreciable results have been observed in each of those groups in the form of better participation and awareness and lower incident rates. I will describe the basic concepts of the process in the remainder of this article.

Start Small and Make It Personal

The tendency of most workers, myself included, is to create a mental separation between work matters and home matters. We also tend to dismiss the possibility that there are many hazards – especially serious ones – associated with routine tasks. Discussing the pros and cons of that tendency is beyond the scope of this article. But in developing the hazard recognition training, my colleague and I theorized that if we could show people how many hazards they could identify while considering a task that isn’t associated with work and seemingly has no or very few related hazards, then the translation to finding the hazards in routine work tasks would become more meaningful. And if we could then get our employees thinking about what it takes to keep their loved ones safe during tasks unrelated to work, we could ask them to apply the same energy to identifying hazards at work that could cause harm to them or their co-workers.

The initial task we use in this exercise is setting a mousetrap. It always surprises people to realize the rather long list of potential hazards – usually somewhere between eight to 12 hazards – they end up with for such a seemingly simple task. Then we identify a slightly more difficult task for participants to consider: changing a flat tire on the side of the road, plus we throw in the kicker that the person who has to change it is their 16-year-old who just got his or her driver’s license. We usually tell the participants that the 16-year-old is their daughter because that resonates a little more with most of them, but either gender will work. I’ve done this exercise with dozens of classes and have never had a list of hazards that was shorter than 30, and a list of 40 or more hazards is not uncommon. The key concept in all of this is that workers are now intentionally thinking about finding hazards where they otherwise might not have looked very hard because what could happen now matters more to them.

Trust Them with Knowledge

Something that often chafed me when I was still doing field work was how leadership seemed to avoid answering questions that began with “why.” It was as if certain information was to be guarded, that I was somehow incapable of comprehending or appreciating what went into the decision-making processes of safety and operations leaders. I don’t say this to offend anyone or cause a ruckus. It is the honest perception that I and my co-workers had at the time. So when my colleague and I began designing this hazard recognition process, it was very important to me that we provide some of the theory behind how safety decisions are made. It’s a cinch to understand that every single hazard cannot be eradicated. Utilities have neither the fiscal nor human resources to do so. Therefore, showing workers how leaders make decisions about applying the resources they do have helps them understand why certain controls are in place and why certain rules and policies are written.

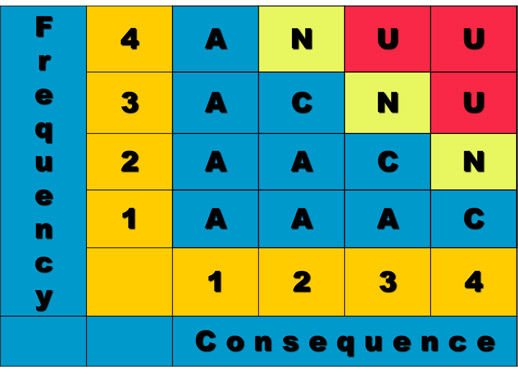

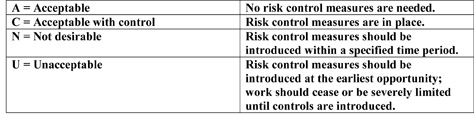

The key knowledge I want participants to leave the training with is an understanding of how to prioritize hazards. If we have a list of 35 or 40 hazards associated with a single task (e.g., changing a flat tire), and we know that our resources are limited, where do we get the most bang for our buck? A brief discussion of risk matrices (similar to the one pictured below) helps workers see that there actually is a systematic method for ranking hazards, that we aren’t just subjectively choosing what to fix or mitigate based on personal preference or whatever is cheapest. The logic of the process also provides a method for looking at the hazards employees encounter in the field and deciding how they can mitigate them and whether or not they need help to do so.

Give Them the Right Tools

Telling people to use this training to identify and mitigate hazards sounds noble, but it isn’t very practical if you don’t provide a way to systematically accomplish it. My colleague and I designed forms – which are easily translatable to electronic formats – that built upon the daily job briefings our workers were already performing, and we also utilized the information previously gathered in job hazard analyses of their various tasks. Using these together with an understanding of the hierarchy of controls provides for a much more thorough examination of the job site and tasks to identify potential hazards, and it increases the likelihood that good controls will be created by the workers right there on the site. The results I have seen support that expectation.

Apply the Process to Their Work

Once you have taken a group through the process, the final test is to see if they get it and can apply the principles to their work. The absolute best-case scenario is to be able to move right from the classroom to a field location and put workers through the paces. In a controlled environment, when you and any other co-trainers have already identified every hazard you can find – and get some help with this; we miss stuff from time to time – put participants to work in teams of two to four people and have them find every hazard they can. Then get them back together in the classroom to examine the lists, prioritize the hazards and decide what the best mitigations would be based on available resources.

If it isn’t feasible to take the group members to the field, use the best photos you can gather that show their real-world job sites and take them through the process in the classroom. While this is not as effective as the hands-on method, it still provides a chance to apply the teachings. And it is imperative that you confirm that the workers can effectively apply what they have learned.

Conclusion

Getting our people to truly see – that is, intentionally seek out and recognize – the hazards that are around them on their job sites every day is paramount to establishing a work culture that values safe production and in which employees see themselves as their brothers’ keepers. It is also critical that workers, having seen the hazards, progress naturally to the process of mitigation. One must follow the other as night follows day. Otherwise, people will continue to get hurt when they shouldn’t. The process outlined in this article can be a very helpful piece of your overall strategy for creating that work culture.

Author’s Note: I will be teaching this process in much more detail on April 28 at the iP Utility Safety Conference & Expo in Orlando, Fla. I would love to see you there. For more information, visit www.utilitysafetyconference.com. If you can’t make it to the conference, contact me at mcaro@trcsolutions.com and I will send you details about the program and help you set it up for your organization.

About the Author: Mike Caro, CUSP, is HSE director for the pipeline services sector of TRC Solutions. He has more than 25 years of utility industry experience, including over 17 years as a lineworker, and holds a bachelor’s degree in biblical studies from St. Louis Christian College.