Exploring Human Judgment and Its Impact on Safety

As a human being, you depend on your own good judgment and the good judgment of others in everything you do. For example, in order to avoid an accident, you depend on your good judgment and driving skill as well as those of the driver in the car approaching you. To create and maintain a safe working environment, you rely on the good judgment of all crew members – including yourself – to carry out tasks with skill and precision.

In part, every individual’s safety depends on the safe decisions of others. When things go well, it often is assumed that everyone involved made good decisions. And when something goes wrong, it sometimes is said that the person at fault used bad judgment. But what exactly drives human judgment? Are there ways that human beings can strengthen their ability to make wise, safe decisions? In the remainder of this article, we will explore the topic of human judgment, including insight on the human brain and some tips to help you improve your decision-making abilities in the future.

The Three Components of Judgment

Human beings form judgments based on a compilation of information gleaned from their instincts, knowledge and intuition.

Instinct is the lowest form of the human condition and part of our DNA. It also is found at the bottom of Abraham Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs. The hierarchy describes humans’ behavioral motivations, essentially stating that all of a person’s needs at one level of the hierarchy must be met in order for that individual to move up to the next level. Every human has the basic instinct to warm up when cold, to eat when hungry, to drink when thirsty and to rest when tired. When it starts to get dark outside, people instinctually think about shelter and safety. These instincts are natural after centuries of programming, but humans must be careful when their instincts are trying to drive a decision that they have carefully planned.

Let’s take it one step further. Workers begin to think about shelter and safety when it starts getting dark outside. What happens on the job when the light is fading and a foreman says, “Hey, let’s get this done – we’re running out of daylight”? In order to deal with such a scenario, human beings unconsciously begin to seek shortcuts and ways to speed up the work, and they may not even be aware that their instincts are taking over their actions. This is when errors can occur.

Being aware that instinct drives human judgment can help everyone plan and work better during stressful situations. The best managers, supervisors and foremen take the human condition into consideration and address it during the planning and execution of work. So, the next time it starts to get dark, engage the crew in a safety stop to discuss the pressures and instincts that may be driving their work, as well as how you’re going to address those pressures and instincts so that the work is completed safely. Or, let’s say line crews are working a lot of hours during a storm restoration effort. As soon as possible, be sure to give those crew members the name and location of the hotel where they will be staying and the expected time and location of meals. With those details squared away, they won’t be thinking about when and where they will eat and sleep, eliminating those items as distractions.

Knowledge and Bias

What a person knows – and what they don’t know – is the second of the three components that drive an individual’s judgments.

In the electric utility industry, lineworkers are expected to have a certain skill set. The steps of an apprenticeship are designed to enable lineworkers to learn. The problem with learning is that human beings will never know everything, so they don’t know what they don’t know, but a human being’s application of knowledge in problem-solving is directly related to what they do know. All of that means that people rely on a combination of their instincts and their personal knowledge to make judgments and determine how to proceed. And that means that when an individual evaluates a situation, that person doesn’t include things they don’t know in that evaluation.

Relatedly – and unfortunately – there are a number of cognitive biases that also impact human judgment, changing behavior and the way people think and thus limiting outcomes. For example, an apprentice who has an idea may or may not contribute that idea depending on the apprentice’s perception of the group leader’s willingness to listen.

While there is no perfect solution to conquering knowledge gaps and cognitive biases, knowing that these issues exist and consistently discussing them on the job can have a significant, positive impact on safety.

Trust Your Intuition

The last of the three components that drive human judgment is intuition, which can be described as knowledge or insight that an individual obtains and believes to be correct, yet the source of the knowledge or insight is unknown. It’s that fine line between conscious and subconscious thought. The human brain works almost full time in the background, shortcutting and making simple decisions. In fact, human beings act unconsciously most of the time. Consider this: Did you actively think about most of the decisions that you made today? For example, did you think about which foot you first put on the floor when you got out of bed this morning? It’s unlikely. When you last drove to work, did navigating that familiar route seem to take a lot of focus, or did you find yourself operating on autopilot part of the time? Most people would report that they did fall into autopilot mode at one point or another.

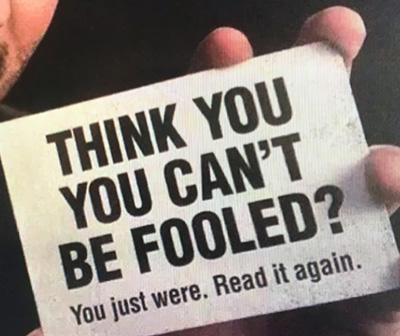

Let’s delve into this concept a bit further. Quickly read the sentence in the photo below.

Most people miss the second “you” in the sentence. That’s because your brain sees and then eliminates the second “you” before you consciously read it since it’s not necessary to understand the sentence. The point here is that your subconscious mind is evaluating things ahead of you all day long. Sometimes you know something isn’t right, but you can’t put your finger on exactly what it is. During the day, while performing low-consequence actions, people listen to that intuition and act on it. When it comes to high-consequence situations, however, people are less likely to act on a gut feeling. Everyone has had the thought that they should or shouldn’t do something – and then they do the opposite anyway. Once they realize their error in judgment, they say, “I knew I should have done that differently.”

In his book “The Gift of Fear,” author Gavin de Becker describes how people sometimes relay their intuition to a group as “dark humor.” When someone has the feeling that something isn’t right, he or she might say, “This isn’t going to work” or “This is going to be a catastrophe.” De Becker then goes on to tell a story about a misaddressed package found at a U.S. Forest Service building in California. Unsure of what to do with the package, the president decided to open it to see what was inside. Upon hearing the decision, one of the managers responded, “OK, I’ll be in my office when the bomb goes off.” The manager heard the explosion as he closed his door. As it turned out, the package was from the Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski.

All of us would do well to explore statements of dark humor when they are made. Listening to intuition can be a valuable tool to help mitigate risk before someone suffers the consequences. Thoughts come to your mind as insight or ideas. When a thought comes to your mind expressed as fear, anxiety, confusion, hesitation or a gut feeling, it’s worth the time to explore it. After all, no one can mitigate a risk if the risk hasn’t been identified. During a job brief or management huddle, listening for signs of someone’s intuition could be the difference between success and failure.

In another book – “The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right” – author Atul Gawande discusses a study done by Johns Hopkins. The study determined that when a surgical team stopped just before surgery to introduce themselves, share their roles and express the risks they saw in their respective parts of the surgery, there was a significant increase in success and improved communication during the surgery.

Again, when we can tap into the good judgment of our crew or team members, we do better. Listening to everyone – from the apprentice to the team leader – explain their perception of the hazards on a particular job can change outcomes. Imagine if, during the job brief, each crew member identified their role and concerns. There would be an opportunity for clear communication between crew members before the job started, including the time to share feelings and intuition that have manifested as a result of the assignment. Keep in mind, however, that perceptions may vary from person to person, so it’s smart to use closed-loop communication and recite back what you think you just heard so that everyone on the crew is on the same page.

Summary

Human beings are complex creatures who use a myriad of informational resources to judge the world around them. The more each of us understands about what drives those judgments – that combination of instincts, knowledge and intuition – the more we can do to improve safety on our job sites.

About the Author: Bill Martin, CUSP, NRP, RN, DIMM, is the President/CEO for Think Tank Project LLC. He has held previous roles as a lineman, line supervisor and safety director.