Understanding and Influencing the ‘Bulletproof’ Employee

Some employees are regrettably willing to take risks, as though they believe that they cannot be injured. This is the challenge of the “bulletproof” employee. To influence these kinds of employees, we first need to understand why they take the risks that they do, and our approach to understanding these employees, as it turns out, is where the challenge starts. By breaking a handful of old habits and adopting a more useful model for understanding others’ decisions and actions, we can become better equipped to tackle this challenge head-on and positively influence these employees.

Dealing with Our Distortions

Understanding the bulletproof employee starts with a look in the mirror. Our efforts to influence these employees are often undermined by a number of bad habits or, more accurately, unhelpful biases that affect our judgment. The word “bias” is often used to describe someone’s prejudice against something or sometimes a person’s favoritism toward something. For psychologists, the word has a slightly different meaning. It is a distortion in the way a person makes sense of the things that he or she sees, hears and so on. In other words, it is our twist on reality. We are often unaware of these distortions because biases can be deeply embedded and operate covertly.

For example, think of a purchase that you made that you would now characterize as impulsive. Upon reflection, you did not really need the item and it probably cost too much money; however, in the moment, you were convinced that it was a reasonable purchase. In the short time leading up to this impulsive purchase, you were subject to the confirmation bias, which distorted your view of reality and had you overvaluing the things that justified buying what you already wanted.

There are similar biases at play when we try to understand and influence the decisions and behaviors of bulletproof employees, which we refer to as “onlooker biases.” As onlookers, we try to make sense of others’ decisions and behaviors, but because we have limited information since we are not inside their heads, we attribute reasons to them. We do so without realizing it and quickly become convinced that our attributions are, instead, observations.

One of these onlooker biases is the fundamental attribution error. This is our strong tendency to overlook external factors – like time pressures and insufficient resources – and focus instead on people’s character when trying to understand their decisions and behaviors. For example, when was the last time you were cut off in traffic and thought to yourself, “That car must have a big blind spot”? If you are like most people, your first thought is that the other driver is aggressive and rude, not that he or she didn’t see you.

When an employee does something that is clearly unsafe, this particular bias leads us to neglect the possibility that the person might have done so because of external influences. We quickly jump to the conclusion that he or she did so because of a personal flaw, such as recklessness.

Onlooker biases present the first challenge to overcome in our effort to positively influence bulletproof employees. If we can abandon the comfortable confidence with which we attribute others’ unsafe behavior to personal deficiencies, we can more honestly and openly explore the problem.

However, if bulletproof employees are not fundamentally reckless and delusional, then why do they willingly take unnecessary risks? The answer: because it makes sense to take unnecessary risks.

It Makes Sense – From the Inside

On an abnormally frigid morning in West Texas, before the sun had risen, a small crew stepped out of their heater-less truck to begin a job. The foreman barked at two of his men, “Get over to the shed and get that heater going before you do anything else.” When the men opened the shed door, they were struck by the strong smell of gas. Unable to see the origin of the gas leak in the predawn darkness, one of the men pulled a cigarette lighter from his pocket and lit a flame to illuminate the shed. It is not difficult to imagine what resulted.

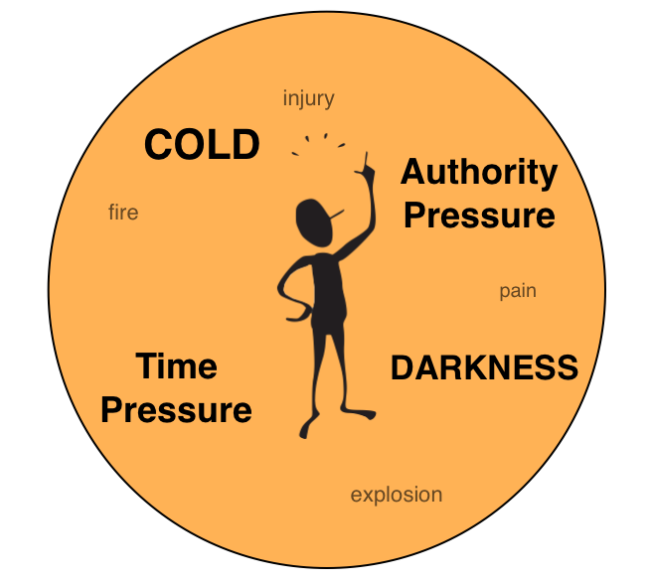

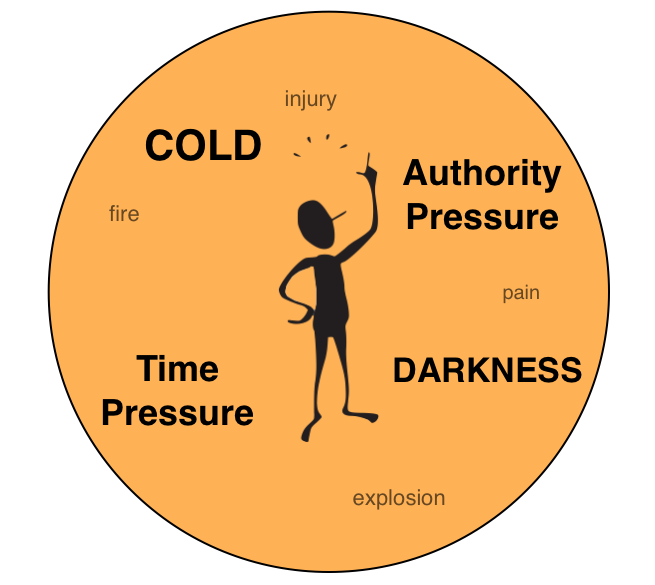

The question that usually follows this example is, “How could someone do something so foolish?” It seems a reasonable question, as the employee undoubtedly knew that the flame from a cigarette lighter would ignite a concentrated gas cloud like the one in the shed. The surprising answer is that it was not foolish. It made perfect sense to do what he did. More precisely, it made perfect sense in that particular moment to do what he did. This is the premise of local rationality, meaning a person’s decision or action is rational given the most salient factors in his or her context. We make decisions based upon the information that is available to us, but that information carries different weight from one moment to the next. When one factor is more obvious or pressing, it is said to be more salient. For the employee who lit a cigarette lighter in a shed filled with gas, there were many factors affecting his judgment, including the need for light, a sense of urgency coming from his supervisor and the discomfort of feeling extremely cold. These factors were more salient to him in that moment than the risk associated with lighting a flame in a gas cloud. From the outside looking in, we judge his decision as foolish because we evaluate the decision from a different context, in which the risk of igniting a gas cloud is the most obvious.

The point is this: If we are to understand and influence the decisions and behaviors of bulletproof employees, we must be mindful that their decisions and behaviors make sense. The key is to uncover those factors that, for them, are more salient than the risks associated with their behavior.

Surprisingly Salient

It is helpful to recognize that some factors are much more significant and pressing in a person’s immediate context than we usually realize. Stanley Milgram’s now famous study of obedience to authority, for example, revealed the surprisingly profound influence that authority figures have on people’s behavior. Subjects in this study were willing to administer what they believed to be potentially fatal electrical shocks to strangers when an authority figure calmly instructed them to do so. Other research has shown that factors as apparently minor as finding a dime in a telephone coin return, or having a deadline moved 15 minutes earlier, can dramatically alter the way that people treat each other.

These studies and many others help us to recognize that what we think should be the most salient factors in a person’s context often are not. From the outside looking in, we do not think that people should have administered what they believed to be electrical shocks simply because Milgram’s researchers told them to, but they did so nonetheless. From the outside looking in, we do not think that employees should scale pylons without sufficient fall protection to finish a job five minutes faster, but they do.

In addition to authority and time pressure, there is one factor that is often surprisingly salient in employees’ decisions to take unnecessary risks. This factor is the perceived need to complete a task without interruption. Psychologists refer to this as a unit bias, which is a distortion in our decision-making process that has us overvalue the importance of completing a single unit or task. A manufacturing line manager illustrated this bias well in an anecdote about his own leadership decision. He had almost finished reviewing a handover report when an employee burst into his office to inform him of a serious malfunction on the line. Instead of dropping everything to attend to the issue, the line manager took a couple of minutes to finish his review of the report. In hindsight, the line manager said, the malfunction could have been catastrophic while there was no real urgency surrounding the report. In the moment, though, the unit bias had this line manager overvalue the importance of completing one task before moving on to another.

In the case of bulletproof employees, this bias often manifests itself when employees choose to take unnecessary risks rather than interrupt what they are doing to remove or mitigate those risks.

A Candid Conversation

The urge to finish a task without interruption is one of many surprisingly salient factors that can play a role in employees’ decisions to take unnecessary risks. While it would be nice to provide a complete profile of bulletproof employees and a single prescriptive strategy for changing their behavior, reality, as usual, is not so accommodating. The reasons behind employees’ willingness to take unnecessary risks can be as variable as the decision-making contexts in which they find themselves. As such, understanding and influencing these employees comes down to an open and candid conversation. The real challenge comes in managing our own covert biases while keeping a keen eye open for subtly influential forces in employees’ specific decision-making contexts.

About the Author: Phillip Ragain is the director of research and development at The RAD Group (www.theradgroup.com), which specializes in human performance, behavioral safety and safety culture solutions. Ragain is the author of numerous articles on human performance in safety, communication and organizational ethics, and he has developed training programs that are currently used by organizations around the world.