Tip of the Spear: A Tactical Approach to Safety Leadership

If you’re looking for ways to assess, select and develop leaders in your organization, the U.S. military can offer guidance.

Leadership is defined as the action of leading a group or organization; it’s a verb. It’s also a skill that is extremely fluid. Leadership style can change depending on the person and the situation, but all effective leaders have some common qualities. When I developed the list below, I initially came up with 68 possible qualities, and while I know each of them has some merit, I eventually narrowed down the list to these 16 qualities that I believe are nonnegotiable.

1. Ability to effectively communicate

2. Ability to influence

3. Ability to inspire

4. Respect and trust (gives and earns)

5. Humility/no ego

6. Willingness to learn/continuous improvement

7. Master of delegation/empowers others

8. Honest/has integrity/is ethical

9. Flexible/able to manage change

10. Vision/forward and strategic thinker

11. Gratitude/gives team all credit and celebrates their successes

12. Industry competence/credibility

13. Teaches/develops other leaders

14. Enthusiastically leads by example

15. Self-aware

16. Demonstrates empathy/earnest caring for the team

How to be a Frogman

If we want to identify and develop leaders in our organizations who possess the qualities listed above, it’s critical to devise tactics to do so.

The U.S. Navy has its own process to assess and select members for its SEAL teams. For a long time, the teams were highly classified and secretive. In recent years, more information about them has become available, giving us some insight into one of the most elite fighting forces on the planet. In this next part of the article, I’m going to explain how SEAL team members are trained and then hand selected based on their skills. This approach is something we in the utility industry can look to when determining who we want to lead our crews.

When most people think about Navy SEAL training, they’re generally thinking of Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL (BUD/S) training, part of which is a four- to five-day training exercise during which SEAL candidates are put through some of the most grueling training any human has endured. In total, BUD/S is made up of three phases and lasts 24 weeks. Simply graduating from this training program, however, does not make you a SEAL. After BUD/S, there’s still SEAL Qualification Training (SQT), an advanced program that takes the individuals who graduated BUD/S and forms a team that can operate in and under the water; from planes, helicopters, ropes and parachutes; on boats; and on foot. If you are one of the 25% or so left at the end of SQT, then you get the honor of wearing the Special Warfare insignia, which consists of an eagle clutching an anchor, a trident and a flintlock pistol.

After you have been on a SEAL team for at least five years and served a minimum of two deployments, you can try out for SEAL Team 6, also known as the Naval Special Warfare Development Group. Once approved by your chain of command, you do your initial screening, which is an extreme version of the regular SEAL physical training test. If you pass the screening, you receive the privilege of sitting in front of the review board. This involves being grilled about topics including your tactics and experience, former employers, service medals you’ve earned, your home and family life, your finances and how much alcohol you drink.

At this point in the process, approximately half of those who started have been cut. The next phase is called the Operators Training Course, also referred to as “Green Team,” a six- to eight-month course that is a much more intense version of normal SEAL training. If BUD/S was the freshman 101 level course, Green Team is where you get your Ph.D.

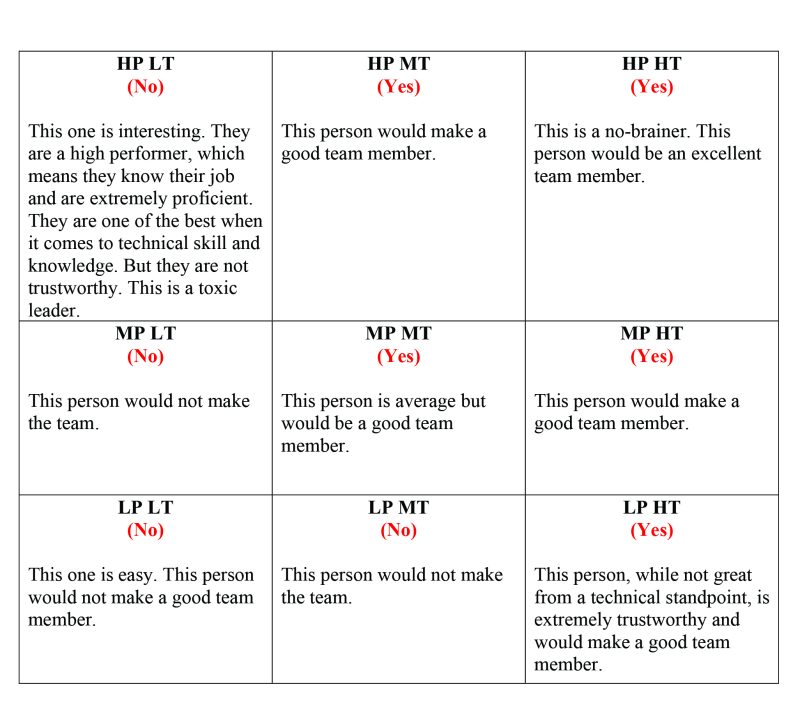

But it’s still not over. Now the current members of Seal Team 6 will hand select who they want with the help of a chart like the one below, which focuses on levels of personal performance and trustworthiness. For example, the middle square represents someone who they believe is a medium performer and has medium trustworthiness.

Let’s look at the chart a little more closely now and think about who we would want on our team.

Someone who is a high performer (HP) with high trustworthiness (HT) – see the top right corner – is a no-brainer; everyone wants this person on their team. And the low performer (LP) with low trustworthiness (LT) in the bottom left corner is easy, too, because it’s likely no one wants this person on their team. What about the rest? Check out the remainder of the chart and consider each type of person.

By using the chart above, you can assess potential leaders from both inside and outside your organization and determine who may be the best fit for the job. In addition, you can identify those individuals who – with the right training – could eventually become strong leaders.

Four Laws of Combat

In summer 2022, I came across a book called “Extreme Ownership: How U.S. Navy SEALs Lead and Win” by retired SEALs Jocko Willink and Leif Babin. I was hooked from the first chapter. Each chapter is broken into three segments. The first details a combat scenario that Willink and Babin experienced during the Iraq War’s Battle of Ramadi in 2006. Next is a principle that explains what the chapter is trying to teach you. The final segment is the chapter’s application to business, wherein the authors explain the principle again, but this time they explain it in terms of the civilian world, using actual events that have taken place in organizations just like yours and mine.

Willink and Babin also discuss four basic laws of combat that, when redefined, apply exactly the same to a Fortune 500 company or a construction site in Anywhere, USA. Following are descriptions of each of the four laws. Review them, and then think critically about the ways you can apply the laws in your own journey as a leader.

First Law of Combat: Cover and Move

In the military, cover and move usually involves laying down fire to allow one of your teammates to move to another location. We’ve seen it in the movies – one of the characters will say “Cover me” and another will stand up and start sending hot lead downrange toward the enemy, forcing them to duck or retreat for long enough that their buddy can run to the next location. Well, we aren’t using belt-fed machine guns in the civilian world, but cover and move still applies. This principle simply means that individuals should have each other’s back and step up when someone needs some help.

Second Law of Combat: Keep it Simple

Keeping things simple is not always all that simple, especially when you have a lot of information to pass along. I used to have a bad habit of sending emails that were so detailed, no one ever had to ask me any questions about the content; that’s because the emails were so long and detailed that no one actually read them. Essentially, the more complicated you make a situation, the greater the chance something is going to go wrong. This is true in everything you do.

Third Law of Combat: Prioritize and Execute

This law is the one that takes the most practice. And just when you think you’ve got it mastered, things change and you must try again. The fact is, priorities shift regularly, and we have to be able to be fluid enough to make the necessary adaptations. The five steps to prioritize and execute are:

- Identify the problem.

- Describe the consequences.

- Take ownership.

- Provide a solution.

- Ensure the solution is implemented.

On a personal note, as a U.S. Army combat medic, I was taught to perform triage when we arrive on a scene. Triage is also useful in business when trying to determine priorities. We can make more progress by attacking things in succession rather than trying to do everything all at once.

Fourth Law of Combat: Decentralized Command

All four of the laws of combat are important, but without this one, none of the other three will matter. “Decentralized command” is the military way of saying “Delegate authority and trust your team.” For toxic leaders, this is the hardest law to follow. Why? Because it means letting others make decisions.

We all know at least one person in a leadership position who is a micromanaging keeper of all information. But the reality is that it’s much easier to run an organization by surrounding yourself with people who are smarter than you are and letting them do the jobs you hired them to do. Trying to control everything within reach is counterproductive. We must remember that leadership is a skill that has to be learned and practiced for continuous improvement to occur.

About the Author: Rod Courtney, CUSP, CHST, began his career in the U.S. military and served as a U.S. Army combat medic from 1990 to 1998. He is currently the HSE director for Ampirical and author of “The 8 Habits of a Highly Effective Safety Culture.” Courtney also serves as a board member for the Utility Safety & Ops Leadership Network. Reach him at rod.courtney@ampirical.com.