The Importance of Matching Evidence Marks in Accident Investigations

I have personally investigated more than 800 incidents involving serious permanent injury, death, equipment failure and structural failure. Time after time, we were pulled in late to assist with investigations in which early investigators had failed to properly investigate the incidents. They had jumped to erroneous conclusions, thus resulting in incorrect admissions, strategies or other actions in the related litigations. When properly analyzed, each incident was shown to have occurred differently than originally assumed, and often a different party or action was the precipitative cause. Finding this out late in the game really hampered effective defense or prosecution, resulting in higher litigation and settlement costs, and even in improper jury decisions because the jury believed the earlier, confusing conclusions.

Two Critical Points

The two critical points in accident litigation are:

1. Matching up evidence marks to accident theories in order to understand and explain how the incident occurred.

2. Determining and explaining the “but fors” – “but for this, that would not have happened” – and explaining them to jury members in a manner that they both understand and believe. This leads back to matching up evidence marks to show to the jury why the theory of liability is correct.

Because we have been a part of so many cases in which early investigators/analyzers erred, we started a seminar in 1990 to train investigators of utility accidents. In the very first hour of the first seminar – while I was explaining the difference between how the older NESC clearance specification system versus the new NESC system would apply to a dump truck line-contact case – a Texas attorney announced to everyone that he could go home now. He explained that they had just had a case similar to the case I illustrated, in which his engineers not only used the wrong edition of the code, but did not know how to use the one they had. The result was that they had sent off a check for $1.2 million that morning to get out of a case in which, if the evidence marks were properly analyzed with the correct clearance requirements, there was no code violation.

I cannot overemphasize how critical matching up evidence marks is to having a suitable outcome to an investigation. You have to test your theory. If your theory is expected to generate marks not found, or if your theory does not explain marks that were found, your theory needs to be re-examined.

An Example Accident

A specialty metals manufacturer had a series of buildings in a large complex. They owned a 34.5-/19.9-kV ring bus that went all around the property, with substations at strategic points that converted to 2.4 kV for service to individual buildings. The 2.4 kV was either used directly in smelting operations or stepped down to other useful voltages for lights and motors. The 2.4-kV breakers at each substation were contained in a building, and cables went up and through walls to towers, from which conductors went to the various buildings.

During World War II, the government built guard towers on the tops of these substation buildings. They were manned 24 hours a day by guards with machine guns to prevent entrance by saboteurs. The roof of one of the guard towers began to leak and water entered the substation building. A request for bids was sent to reputable contractors. The cost was very high because the area was only 12 feet by 14 feet and setting up appropriate fall protection would cost as much as or more than doing the work. The bean counters made the contract group send a bid request to a roofing firm that had earlier given a low bid. Over the objection of the safety department, this group got the bid. The reason for the objection was that the safety department had to stop them on the last job because they were working without fall protection.

The contract required the roofers to gain entry by going to the closest gate to the work. The work was to begin during a two-week period after the roofers finished another job. The safety department was set up to notify the electrical group to de-energize the section of 35 kV going over the substation guard tower when they arrived. In the safety plan, by the time the safety group escorted the roofers to the building and went over their plan for safe work – which would take about 30 minutes – the electrical group would have de-energized the 35 kV and visibly grounded it so that the ground set could be seen from the work site. This would only take about 20 minutes.

A Change of Plans

Instead of going to the designated gate, the roofers entered the gate through which they had entered for the previous work. A guard remembered them and let them in. This later turned out to be a crucial error. Three men in a small truck with three ladders entered at this incorrect gate and wound through the property to the building. The driver helped the other two men remove the ladders from the truck and lean them onto the lower level of the substation building. He looked at all of the wires coming out of the building’s guard tower area, which were going to the adjacent wire support tower and onto the nearby buildings. He admonished the crew as he left: “Look out for them there wires, they’s everwhere.”

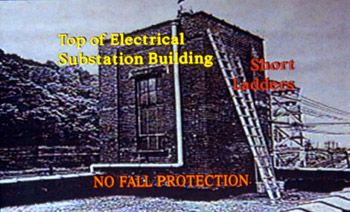

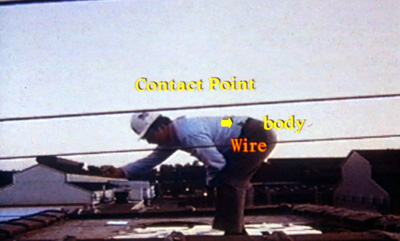

The roofers used one ladder to access the roof of the breaker building and leaned two others against the side of the guard tower. Neither reached the top of the wall, which was covered with 22-inch-wide terra cotta tiles that had to be removed before changing the roof membrane (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

One of the 19.9-kV wires crossed over the opposite edge of the tower. Because the roofers went in through the wrong gate and did not give the safety and electrical groups the opportunity to have it de-energized, one of the roofers was electrocuted fewer than 15 minutes after he was dropped off.

Examining the Evidence Marks

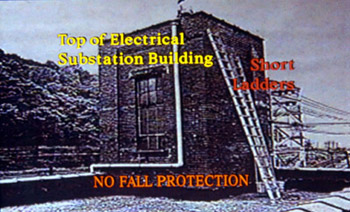

To replace the roof membrane, the crew first had to remove the wall cap tiles around the edge of the roof. I was told that the tiles were made with an elevated section at one end that would overlap the end of the next tile, as shown in Figure 2. Installation had to start with the corner pieces and then build out to the center of each wall, where pieces could be cut to the right length. To remove the tiles, the process had to be reversed. It also had to be done carefully because no replacement tiles were available.

Figure 2

Figure 3

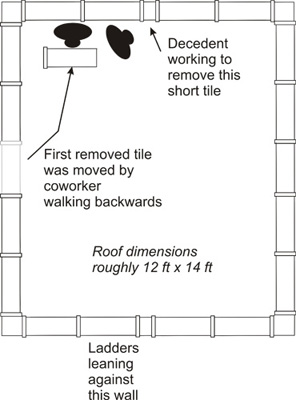

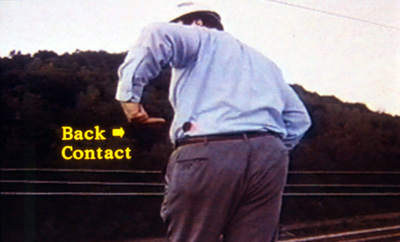

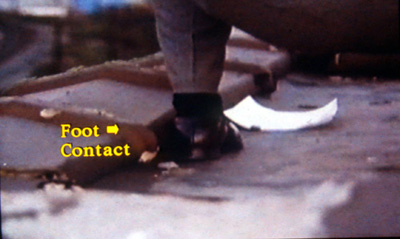

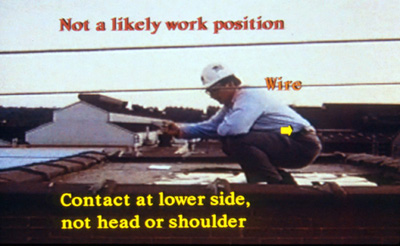

I was told that the man who was working in a crouched-down position on the outside wall – opposite the ladders in Figure 3 – had hit the energized wire with his hammer while trying to chip out the center piece. If that had been the case, you would expect to see burn marks on him in places similar to those shown in blue in Figure 4, inside his right hand and probably on the bottom of his feet. I say “probably” because it turned out that the roof membrane was rubber and insulating.

Figure 4

The actual burns are as shown in red: on his left back side at about a 45-degree position and on the tops of the outside toes on his left foot. Those were the marks that had to match up with the accident theory. The lack of marks on his right hand – he was right-handed and the hammer was found on the right side of where he was working – indicated immediately that the theory was wrong. Note: If you do not have a drawing to mark up like the one in Figure 4, you will need one.

In addition, the marks on the decedent’s left foot could only come from one place: the concrete grout under the edge of the terra cotta tile. The orientation indicated that he had to have been oriented almost parallel, but at a slight angle to the wall because his big toe was not affected. Further, I considered the probable actions of a man on a roof. If he had been crouching down as I was initially told, he would have been on the balls of his toe joints, which is an unstable position for someone working at the edge of a roof more than 30 feet in the air above railroad rails and crossties. If he fell off the roof, he would be a dead, crumpled mess. Your inner ear won’t let you do that. You want a stable position.

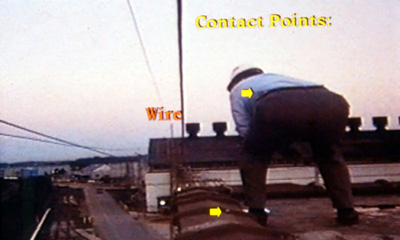

Recreating the Accident

To help determine what had actually happened, I recreated the accident (see Figures 3 and 5-9). Because the workers had not used fall protection, we went to great pains to rearrange the fall protection for each photo so that you would not see it, not to mention all the other people up there in buckets lining the edge of the roof. I could not have fallen to the ground if I had tried. And, yes, I first watched as the line was opened and grounded, and I could see the ground set from the tower, just as would have been the case had the workers followed the contractual requirements. Note: The new roof membrane was thicker, so my foot did not go under the tile, as the roofer’s foot did.

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

If the accident had occurred as I had been told, the decedent would have had burn marks on his right hand. If he had been crouching down and had fallen over into the wires, he would have had burn marks around his head or neck because that is the level of the wire, as shown in Figure 7 depicting the crouched work position. The evidence shows that the work position was not an unstable crouching one, but rather a stable one in which the worker had both feet firmly planted on the roof and one foot under the tile to keep it from slipping.

Note how stable my work position is in Figures 8 and 9. There is no way that I can contact that wire unless I am in the act of falling off the roof. This is where the rest of the detective work comes in – and matching evidence marks was crucial.

Look now at the photo of the roof in Figure 10. You can see the hammer still laying on the tile where the decedent was working. You can also see one full piece of terra cotta tile laying near the side where he was working, but it is not his. This is the first piece taken off by his co-worker. Look closely and you will see the big end made to overlap the next piece. It is on the left in this view. You can also see a little of the concrete grout on the right end.

Figure 10

Additionally, look at how close this tile is to the two wall sections. It is placed so that it will interfere with trying to take off those tiles. That makes no sense until you match the marks. If the co-worker had picked up that tile from the left side wall – just out of this photo – and walked it over to set it down, the big end would have had to have been on the left as he picked it up. However, that was not the case. The big end was on the right. That means that the co-worker had to have picked up the tile and backed it over to that area. Look how little room there is between that tile and the wall. There is little space for your feet.

Conclusive Evidence

As a result of all of this, the following was my conclusion: The co-worker picked up the tile and backed up to set it down. The top area was only about 12 by 14 feet, and he walked it backward too far. When one of his feet touched the tile, he started to fall off the building. His natural reaction was to drop the tile and move his arms backward as he leaned back onto the building, trying to regain his balance. His rapidly moving left arm knocked the decedent off the building. But for the wire, he would have fallen to his death. When he contacted the wire on his way off the building, his leg muscles contracted and, with his foot caught under the tile, he jumped back onto the building where he died.

When I ran through the only logical scenario that fit all of the evidence marks, the reaction of the safety manager – who was in his 70s and had been working there since he was 11 – was, “So that explains it!” All of us gasped “Explains what?” at his reaction. He had been around all manner of horrific accidents and had interviewed countless survivors and witnesses, and he had never seen anyone essentially go to pieces like this co-worker did when discussing the accident. This is not unusual; sometimes your brain knows what happened, but won’t let it rise to consciousness until such time as you are ready to deal with it.

The end result of all of this was that the manufacturer was found responsible at trial because their guards let the roofers in without making them go to the right gate and through the safety check. If the job had gone according to plan, the line would have been de-energized and fall protection would have had to have been installed. However, because we were able to explain what happened to the 100 percent belief of the jury, the amount of money the manufacturer had to pay was very small compared to what had been expected if the jury found for the plaintiff. All involved believed that the award would have been about four times larger if the original theories had been presented to the jury. What saved this case was matching up evidence marks and letting them tell the story.

About the Author: Allen L. Clapp, PE, PLS, is president of the Power & Communication Utility Training Center. He has served on NESC subcommittees since 1971 and was NESC chair from 1984 to 1993. Clapp also served as chair of the ANSI Z535.2 Subcommittee from 1992 to 2008 and was an OSHA instructor for more than 20 years. He can be reached at allenclapp@pcutraining.com.

Editor’s Note: The contents of this article are copyrighted by Clapp Research Inc. and used with permission.