Performance Improvement: Barriers to Events

For anyone who has worked toward improving the safety performance of an organization, you are consistently led back to the fact that people keep making errors. If we could just stop people from making mistakes, we wouldn’t have all these accidents, right? Right. It’s true. If people didn’t make mistakes, we would have far fewer accidents and events. What is also true is that people are fallible, people make mistakes, and people will continue to make mistakes regardless of how much we wring our hands and tell them to be more careful. Without understanding and accepting these truths, there can be little progress in minimizing the number and severity of accidents we experience.

Human Fallibility

Historically, roughly 70 percent of accidents and events are initiated by human error. If you were to go through your accident and event data, you would likely come up with a similar number.

Most people make about eight to 10 errors per hour. This often doubles when we become stressed or are under time pressure. However, most of those errors have minimal consequences. If I take the wrong turn off the freeway, it may slow my progress a bit, but then I can get back on the freeway and life resumes as normal.

So, if we can’t keep people from making errors, and human errors are causing our accidents, what shall we do? Is there no hope? Of course there is hope. Here are two things we can do to reduce the number of mistakes made and minimize their consequences:

• We can develop controls that reduce the number of errors we are likely to make during high-risk or critical tasks.

• We can put barriers in place so that when we do make a mistake, the barrier will prevent or reduce the severity of the injury or event.

We’re never going to prevent all errors, but we can focus on the highest-risk tasks and determine what safeguards are needed to protect our people and equipment when someone inevitably makes an error.

Understanding Hazards

There are many high-risk tasks in the electric utility industry, including:

• Working with energized equipment

• Working around rotating equipment

• Working from heights

• Walking and driving in difficult terrain

• Excessive heat and cold

• Driving in traffic

Although this is far from a complete list of the hazards electrical workers regularly face, it’s a peek at a few hazards experienced every day by our field workers. With so many exposed to these high-risk situations all day long, robust programs are necessary to ensure our people are able to safely go home to their families every day.

To keep our people and equipment safe, we must place some type of safeguard between the hazards and people or equipment. There are different types of safeguards that may act as defenses, barriers or controls. These safeguards are there to cope with unplanned and unwanted events that are often a result of a human error. Fortunately, we already have many of these safeguards in place right now.

Defenses are part of everyday life. Driving a vehicle is a risky job that most of us participate in regularly and there are many safeguards built into driving a car to help keep us safe, such as:

• Traffic lights that signal drivers to proceed or stop at intersections

• Painted lines down the middle of roads that designate lanes

• Speedometers that help the operator control the speed of the vehicle by indicating the speed

• Drivers’ licenses, which provide proof that people are qualified to operate automobiles

• Seat belts and air bags that mitigate the effects of collisions

Similarly, the high-risk tasks we have at work also have safeguards built into their processes to keep us safe. Some of these safeguards include:

• Training on the proper way to do our jobs and use equipment

• A safety manual that defines methods of avoiding accidents

• Equipment safety locks to avoid inadvertent equipment starts

• Fall protection when working at an elevation

• Tagging and clearance procedures to use before working on the electric system

• Tailboards and briefings used before jobs to ensure everyone is on the same page

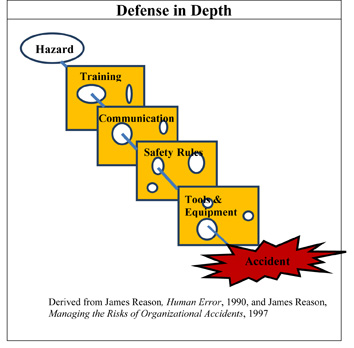

Defense in Depth

Unfortunately, all defenses have the possibility of failure. Since there is no such thing as a perfect defense or set of defenses, multiple, overlapping defenses are often needed. “Defense in depth” is achieved by systematically and redundantly embedding defenses in an overlapping manner so if one defense fails or is ineffective, others will fulfill the same function.

Let’s use the practice of switching as an example. Extra high-voltage (EHV) switching is high risk because a human error can result in severe injury, equipment damage and unplanned outages. Additionally, it is a complex and unforgiving task. There is a specific order and method of switching that allows little room for error. There are irrecoverable acts performed during the process and once the action is completed, there is no way to undo it.

As a result, there are defensive layers built into the EHV switching process. Following are some common safeguards used during EHV switching:

• Employees involved in the switching process are trained in the switching process.

• There is a safety manual that defines the rules used during switching.

• There are maps of the electric system configuration so all energy sources can be located.

• A dispatcher with access to electric system information directs the field switcher’s activities.

• A switching order is written and used as a step-by-step instruction guide during the switching process.

• Employees keep their places during the switching process by marking off each step as it is completed.

The Swiss Cheese Model

James Reason, author of several books about human error and improving performance, developed a visual model that demonstrates how these layers of defenses work. He likens the layers to Swiss cheese.

The holes in Swiss cheese represent flaws that exist in our defenses. Eventually, the holes will line up and when they do, there will be a large-scale accident or event. Our efforts to improve performance can be thought of as trying to get rid of the holes or at least making the holes as small as possible.

Let’s look again at the defenses used during EHV switching. What are some of the flawed defenses that could exist in our switching process?

• The author of the switching order mistakenly leaves out a step.

• Electric system maps are not well maintained and all energy sources are not identified.

• The equipment in a switchyard is not adequately labeled and the field switcher operates the wrong equipment.

• A field switcher loses his place in the switching order and skips a step.

• The requirements in the safety manual are vague and not consistently reinforced.

Good News and Bad News

If any of our defenses are flawed as described above, a switching event or accident could be the result. If additional defenses fail to protect – such as failed relays – the event just gets bigger and bigger. The good and bad news is that whenever a large-scale event occurs, either the current defenses are flawed or defenses are not in place.

More specifically, the bad news is that the existence of flawed defenses results in repeated events and will eventually result in a large-scale or serious event. Maintaining consistently strong defenses is an organizational issue and organizational issues can be difficult and expensive to improve.

The good news is that when the defenses are robust and strong, it affects the entire organization and there will be sustained, improved performance throughout the organization.

It is important to remember that we still need to remain diligent in trying to minimize the number of human errors we experience. However, we also need to know that human error will never be eliminated and we need to be prepared for these errors by:

• Developing controls that reduce the number of errors we are likely to make during high-risk or critical tasks

• Creating barriers so that when we do make a mistake, the barrier will prevent or reduce the severity of the injury or event

Strengthening our defenses is the most reliable and consistent method of keeping human errors from becoming major events, accidents or fatalities.

About the Author: Kathy Ellsworth, CUSP, has 30 years of experience in the electric utility industry and has worked in transmission and delivery as well as nuclear generation. Ellsworth is experienced in safety, human performance improvement, training and program assessments, and she holds a degree in behavioral science. As a consultant, she is dedicated to helping leaders understand how to influence employees’ behaviors to reduce the number and severity of accidents and events within their companies. Ellsworth can be contacted at kathy@estrellahpi.com.