Getting to the Heart of At-Risk Behaviors with Facilitative Learning

This educational technique is ideally suited as a resource for those wanting to improve the effectiveness of safety training.

In a recent workshop with a client in southeast Louisiana, a breakout session reached a tipping point. The rhythmic flow of dialogue among the seven supervisors in the group found an unscripted but purposeful path of its own. The task given to the group involved identifying at-risk behaviors or shortcuts likely to occur in their work environment. Participants were also asked to discuss motives for the identified behaviors and strategies for shifting perspectives regarding them. The intent of the three-part exercise, which was deliberately constructed to achieve the resulting outcome, was to pull information from the collective experiences of those in the session needed to improve operational safety. My role in the process wasn’t to instruct but to guide this group learning experience.

The described scenario characterizes an educational technique commonly known as facilitative learning. A construct perfectly aligned with the needs of the emerging workforce, the process results in a transformational experience for those involved. Based on adult learning principles, it’s also ideally suited as a resource for those wanting to improve the effectiveness of safety training.

Recognize Limitations

To recognize the limitations of a traditional chalk-and-talk approach to safety training, one doesn’t have to look very far. Over the course of my career, working with clients across a wide spectrum of industries, I’ve received countless examples of mindless behaviors that resulted in serious injury or death. With rare exceptions, the policies, procedures and standard practices needed to prevent those tragic events already existed. Furthermore, training and qualification processes to verify understanding of defined expectations in job performance were most often in place. And yet, that wasn’t enough.

As an example of a firsthand account, a safety director for a co-generation facility in the Southeastern U.S. shared with me details involving the death of a coal unloading operator. The operator had been assigned the role of spotter in the movement of railcars on a neighboring facility. As part of his duties, the operator was limited by procedure – as conveyed through annual training – to walking the track to identify obstructions. The primary role of the spotter was to ensure safe movement of the 120 coal cars being positioned for unloading. At some point during the course of his shift, the operator made the decision to ride on the side of the lead railcar during movement, a time-saving practice that had developed over a period of months and one that other spotters later acknowledged doing themselves. As for the cause of death, the operator attempted to ride on the side of a railcar through a coal-shaker shed where several very narrow clearances existed. In proceeding into the shed, he was caught between the affixed ladder on the lead car and a vertical support beam for the structure, instantly suffering fatal injuries upon contact.

The described scenario exemplifies why a better understanding of human behavior is essential and highlights why a new perspective for learning and development is needed, especially in high-hazard working environments. Within every industry, common at-risk behaviors exist. These behaviors are voluntary actions involving elevated or unnecessary levels of risk, incurred for an anticipated benefit that outweighs any perceived cost or consequence. Routinely recognized as taking shortcuts or chances in the performance of a job, at-risk behaviors occur far more frequently than we may realize. They are often viewed as involving poor judgment and are highly representative of our irrational nature. In many instances, they’re precursors to serious injuries and fatalities (SIFs). If a shift in behavior is needed, a facilitative approach is well worth considering.

But while most SIFs are the result of at-risk behaviors, most at-risk behaviors don’t result in harm or loss. This juxtaposition is a primary reason why traditional instructional models have limited effect on behaviors. When a chance or shortcut is taken without harm or loss, the behavior is reinforced. When the behavior results in an anticipated benefit, it’s intrinsically rewarded. This outlined process is a slippery slope upon which bad habits form.

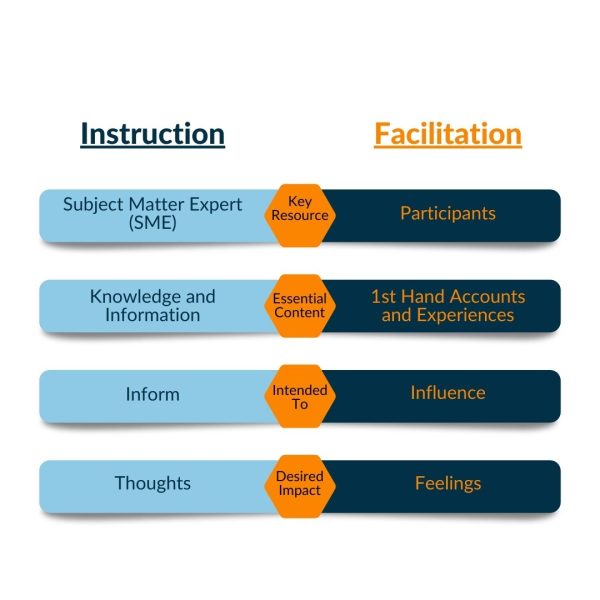

The role of habits is commonly overlooked in the administration of workplace safety. It’s also seldom accounted for during instructional design. Training techniques used most often in the workplace are instructional by nature. A subject matter expert conveys knowledge that trainees are expected to retain, recall and later apply. While facts, figures and information are important, they’re not inspirational or moving for adults. This is especially true when information received is counter to actual experience.

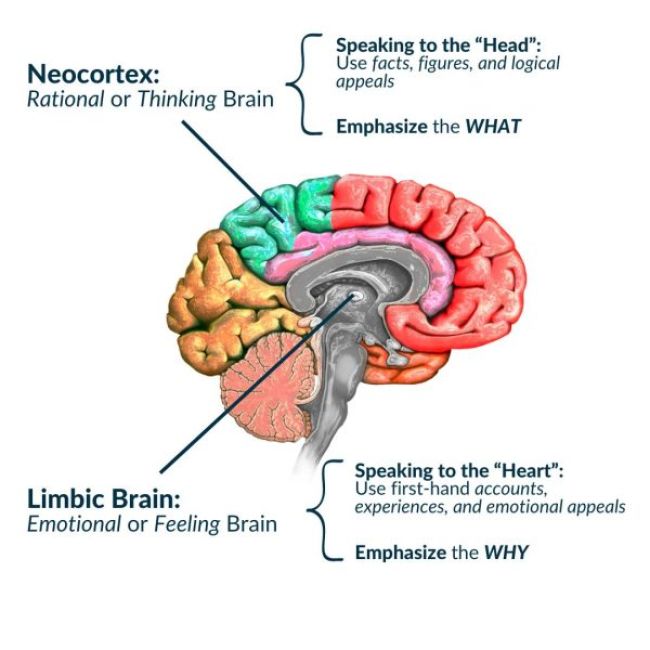

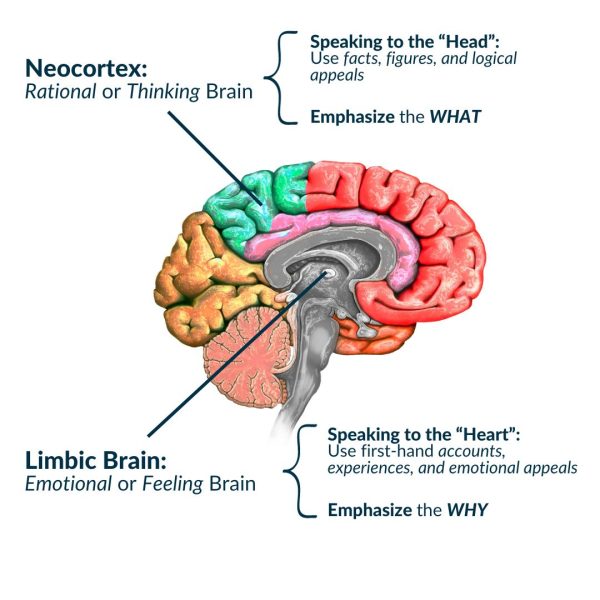

As humans, we process information in several fundamentally different but important ways. Knowledge received for the purpose of shaping thoughts is handled primarily by the neocortex region of the brain. This “thinking” brain, as it’s often described, processes analytical data, logical reasoning and higher-order content well. In contrast, the limbic region or emotional brain is where automatic and intuitive responses originate. The source of feelings, the emotional brain handles exponentially more information than the thinking brain and operates routinely on autopilot, below our threshold of awareness. The limbic region is also where most real-time decisions are made each day. To improve the effectiveness of learning and development, it’s important for instructional designers to account for how conveyed information is received and processed. Most importantly, we must focus more on influencing decisions and less on controlling behaviors. As a rule of thumb, while knowledge makes you think, it’s emotions or feelings that lead to action.

Create a Shift

A goal of facilitative learning is to create a shift in how employees feel about a topic, situation or circumstance. Instead of focusing on content shared by a subject matter expert to inform, emphasis is placed on the learning process and the collective experiences of those in the session to influence. This shift in design transfers primary responsibility for learning from a central authority figure or subject matter expert to the participants involved in the learning cohort. Emphasis is placed on creating dialogue involving actual scenarios, specific to challenges faced, and promoting discourse on possible options in response to them. When effectively executed, this process surfaces the consequences of at-risk behaviors through the collective accounts and experiences of the learning participants.

If we could rewind the hands of time, the opportunity to reach those lost on the job wouldn’t involve doing more of the same. Impacting those suffering harm or loss to the degree required to alter their course of behavior would require a shift in perspective, something knowledge and information alone likely wouldn’t do. To impact perspectives, we would need to focus more on the why, not the what. This redirection in strategy requires reaching the heart – not just the head.

For anyone interested in facilitative techniques and open to giving them a try, there are several important points of distinction worth noting. An instructor presents information from a lesson plan whereas a facilitator guides the learning process. In a workshop setting, an instructor’s goal is to provide the right answers. A facilitator focuses on neutrality and providing the right questions needed to prompt dialogue, discovery and reflection. As for achieving desired outcomes, an instructor is responsible for determining what students need to know. In a facilitated session, participants work with the facilitator to determine what information and skills they need to obtain.

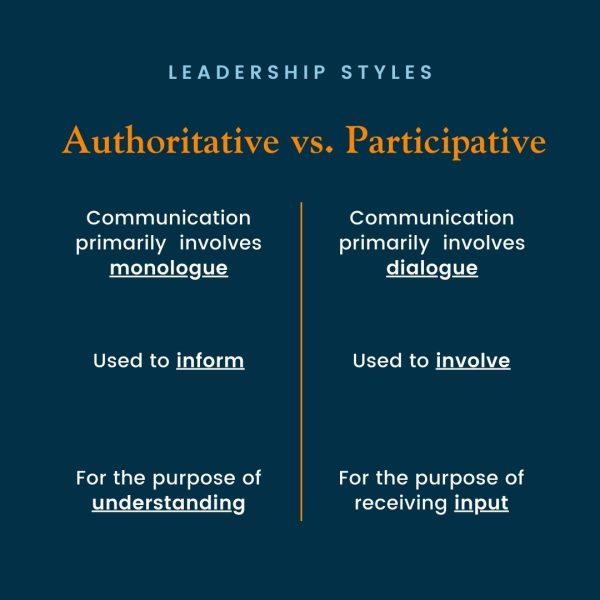

Aside from the benefits facilitative learning offers in helping shift perspectives to reduce at-risk behaviors, the collaborative nature of the process also aligns with management practices most preferred by Gen Z. Whereas a traditional instructor-led training session is authoritative by its very nature, facilitation is participative. The incoming generation’s most preferred leadership style and management practices are participative.

Learn More

As for learning more, there are numerous resources available. OSHA offers a 52-page brochure titled “Resource for Development and Delivery of Training to Workers” (see www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/osha3824.pdf). The document covers principles in adult education, highlights the criticality of past experiences among participants, and outlines the role of facilitators in leading workplace safety discussions. Other options available on the web include resources from both public and private organizations. While some content is free, access to other information is available only through purchase.

For more formal training in facilitative learning, check with local universities or community colleges, especially those with teaching or educational curricula. While some may offer only on-campus instruction, others will offer online or other remote options for participation.

Whether or not you subscribe to one learning theory over another really isn’t important. Having more tools in your kit is. If growth or improvement is desired, changes in strategy are in order. Recognizing and responding to developmental needs more holistically is a key to success and ultimately what we should all be striving to do. Where it doesn’t now exist, facilitative learning is a resource in learning and development well worth considering.

About the Author: Joseph White is the director of AEU LEAD, a management development company specializing in the specific needs of frontline supervisors. He has more than 30 years of operational safety experience, the majority of which was with DuPont, where he led a task team assembled to develop the next generation of safety practices using advancements in neuroscience as a foundational basis. Reach White at joe.white@aeulead.com.

- Determining Reasonable Energy Estimates

- What’s Missing in Your Training?

- Game-Planning for Safety

- February – March 2024 Q&A

- Pattern Disruption: Don’t Start with ‘Why’

- ESG: Health and Safety Obstacle or Opportunity?

- FR/AR Apparel Use: Are Your Workers Properly Trained?

- Getting to the Heart of At-Risk Behaviors with Facilitative Learning