Designing Safe and Inclusive Work Systems for a Neurodiverse Workplace

Neurodivergent workers may struggle to navigate work systems that don’t accommodate their needs, making them vulnerable to errors, accidents and injuries.

Editor’s Note: Incident Prevention readers’ initial reaction to the following article might be, “HIPAA?” You are encouraged to check for yourself, but HIPAA – the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act – does not apply to the methodologies the author presents (see www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-individuals/faq/index.html). Incident Prevention recognizes that the author’s work is a deeper dive into the values of human performance recognition. The information presented can improve training and analysis by properly accommodating individual human characteristics that affect both learning and performance. You are encouraged to read on.

Our work systems are based on neurotypical norms and expectations. Neurotypical workers make up most of the workforce, and these workers fit easily into these work systems because they are tailored for them. However, neurodivergent workers make up a significant minority, estimated between 15-20% of the population (see https://academic.oup.com/bmb/article/135/1/108/5913187). These workers have a range of neurological differences that include cognitive conditions such as ADHD, autism, dyspraxia, dyslexia and dyscalculia.

Neurodivergent workers may struggle to navigate work systems that do not accommodate their unique ways of processing information or consider how they interact with their peers and environment. These struggles make them vulnerable to work errors, accidents and injuries.

Let’s explore how to get beyond traditional work systems to address the needs of a neurodiverse workforce, starting with a few definitions. Then we will look at the different strengths and challenges of neurodivergent workers. Finally, we’ll learn how to build work systems that support inclusion and mitigate the risk of incidents.

Definitions

Understanding some key definitions helps clarify the concept of neurodiversity and fosters a more inclusive and supportive environment.

- Neurodiverse: Refers to a mixed group that includes both neurotypical and neurodivergent individuals.

- Neurotypical: A person who thinks and processes information in ways that are considered standard or typical in society.

- Neurodivergent: A person who identifies with one or more unique ways of thinking and processing information. This person’s brain diverges from what is considered typical in society. Neurodivergence does not determine cognitive ability, intelligence, knowledge or aptitude.

- Neurominority: Any neurodivergent group that differs from the neurotypical majority in terms of brain function and behavior.

- Acquired neurological conditions: Conditions that develop over time rather than being present from birth. Examples include mental health issues such as anxiety and depression.

Language shapes our understanding of diversity and human experience. Educating workers about respectful terminology is a great place to start.

Strengths Associated with Neurodivergent Workers

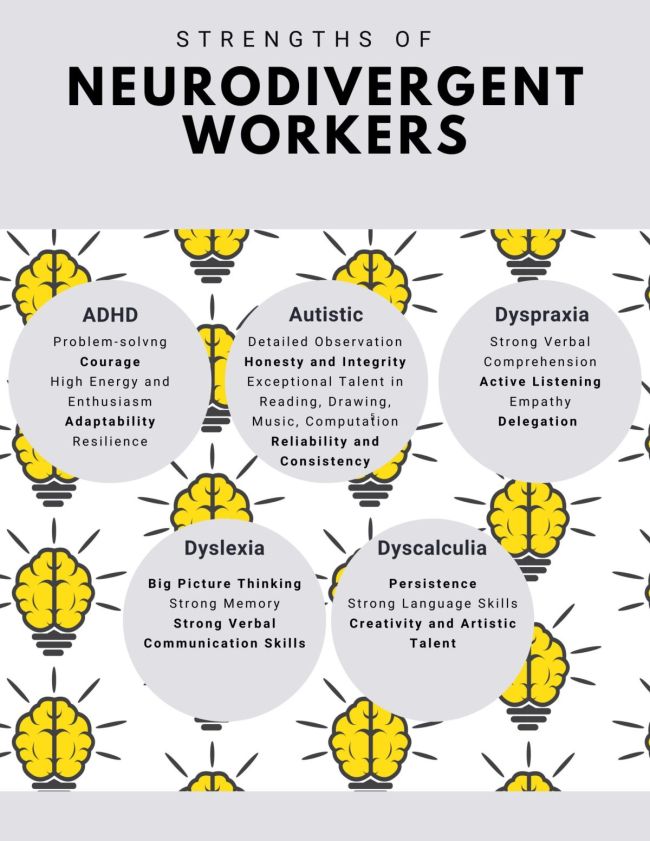

Neurodivergent workers bring a unique perspective to the workplace. Their diverse way of thinking, problem-solving skills and creativity contribute to innovative solutions that may not be present in more homogenous teams. Figure 1 details some of the strengths associated with neurodivergent conditions.

Common Challenges of Neurodivergent Workers

Many workers do not know they are neurodivergent. However, they usually sense something is “off.” They may be confused about why they struggle to complete certain tasks compared to their neurotypical peers. They may have been unfairly labeled as lazy, unreliable, incompetent, antisocial or overly sensitive. They may even start to believe these labels, introducing self-doubt and feelings of inadequacy.

Even if they are aware, neurodivergent workers may feel pressure to fit in and conceal their neurodivergent traits. This is referred to as “masking.” Masking can lead to emotional and mental exhaustion; loss of authenticity; increased stress and anxiety; social isolation; and burnout.

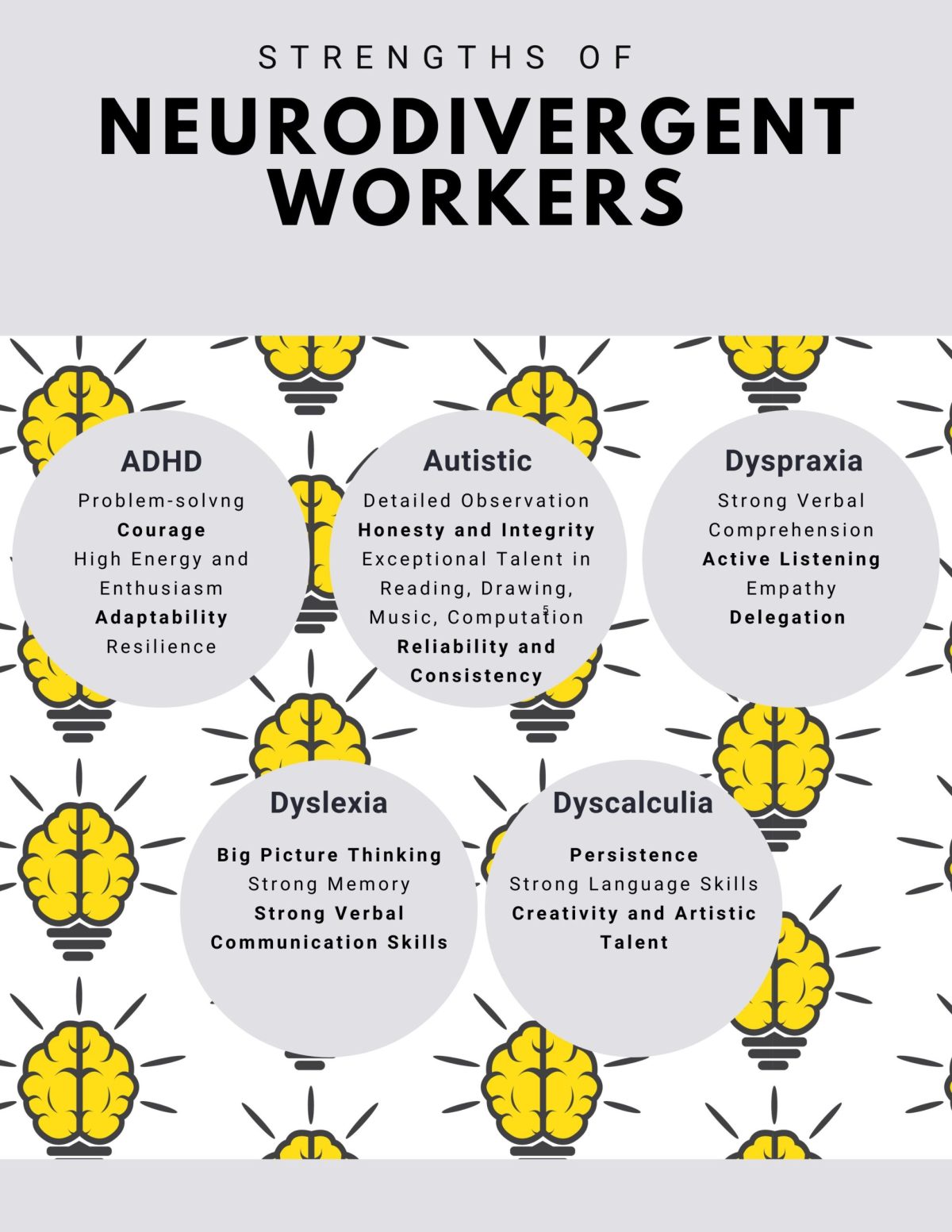

Figure 2 below describes common challenges associated with neurodivergent conditions. A neurodiverse worker may not experience every challenge listed.

Inclusive work systems not only help neurodivergent workers but also neurotypical workers who may find themselves struggling with mental health issues (acquired neurodiversity) or neurological illnesses that place them in the neurominority.

Sensory sensitivities, communication issues, and attention and focus problems are three primary challenges experienced by neurodivergent workers that may contribute to safety incidents.

1. Sensory Sensitivities

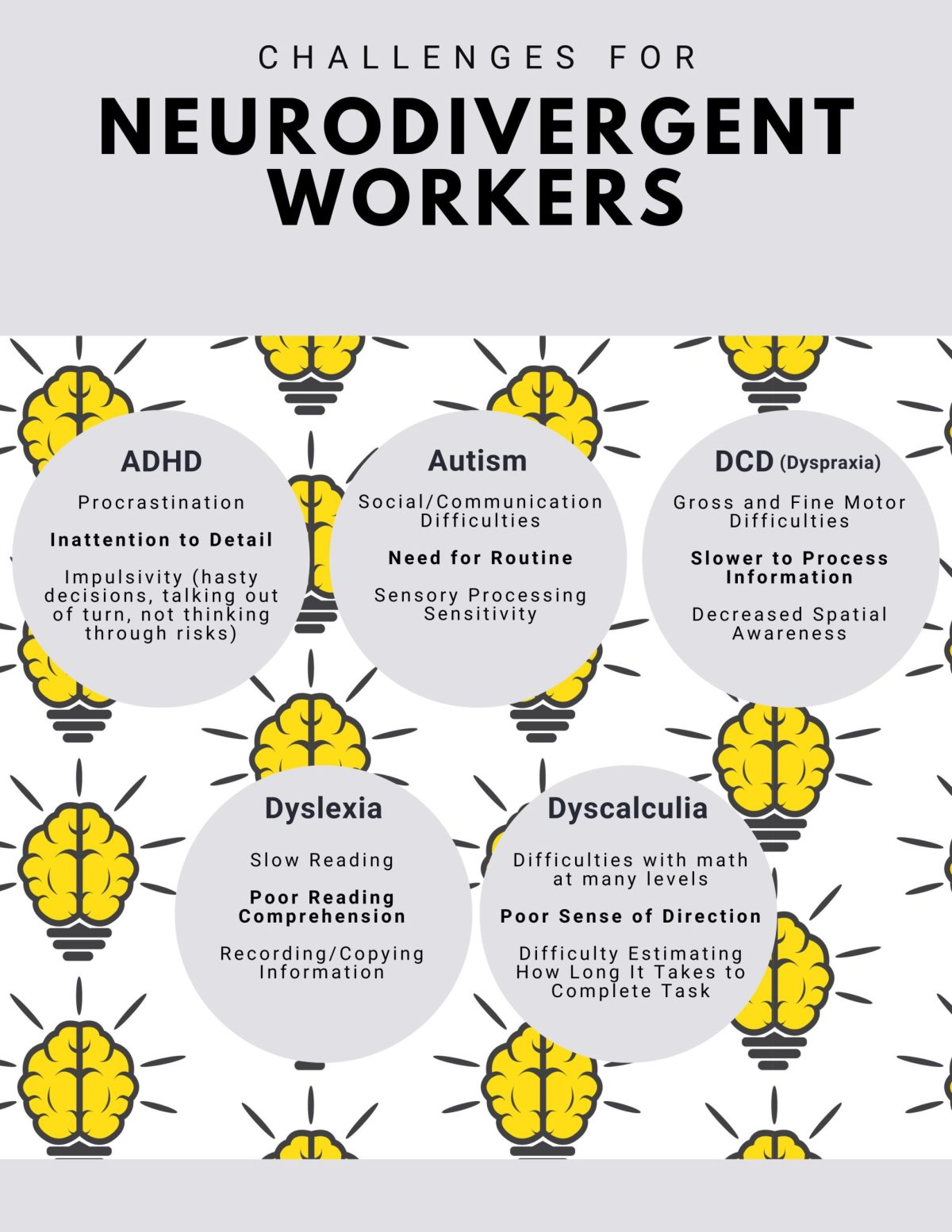

Neurodivergent workers often have an atypical sensory experience. Visual, auditory, olfactory, tactile, taste and temperature preferences vary and are experienced differently compared to neurotypical workers. These differences significantly impact their daily work.

For example, an autistic worker may find it overwhelming to work in a noisy environment. Sensory overload may contribute to extreme emotional and physical reactions (e.g., meltdowns and shutdowns) and an inability to respond to emergency situations.

Below is a sensory sensitivities checklist that can be duplicated to aid with creating accommodations that may help to avoid accidents and injuries on the job due to sensory overload.

A sensory-friendly environment reduces the chance of accidents and injuries by helping the worker to maintain awareness.

2. Communication Issues

Neurodivergent workers experience communication differently than their neurotypical peers. Some neurodivergent workers may need written communication while others need spoken communication and/or a different type of visual communication.

A worker with ADHD may be distracted by both external interferences (noise, movement) and internal interferences (thoughts, daydreams). Since the worker’s focus is frequently shifting from what is being communicated to internal thoughts and external stimuli, there may be gaps in their understanding, and they may struggle to maintain attention to lengthy conversations and detailed instructions.

Autistic workers may have difficulty interpreting facial expressions, body language or tone of voice. They often experience anxiety trying to interpret sarcasm, metaphors and idioms. These workers need direct and literal communication. Otherwise, they may spend a significant amount of time and mental effort deciphering the intended meaning of the communication.

Dyslexia primarily affects reading and writing skills. Communication that requires quick reading comprehension or note-taking may be a challenge. Speech-to-text tools can help these workers with emails and taking notes.

Dyscalculia makes it difficult for workers to understand any communication that involves numbers. They could also struggle with navigational direction, such as traveling to a specific address or finding a location within a large plant. They may need to use supportive tools like calculators, a GPS or a facility map.

Dyspraxia can impact a worker’s speech, making it harder for them to convey their thoughts clearly. Dyspraxia also affects the motor coordination needed for typing and writing. Giving these workers time to express themselves, and offering ergonomic keyboards and mice, may assist them with ease of communication.

Don’t assume that poor communication from a worker means that they do not care about their job. Recognizing differences and understanding unique communication needs will promote a supportive work environment.

3. Attention and Focus Problems

Hazard recognition and adherence to safety protocols require attention and focus. There are much better ways to support neurodivergent workers than to tell them to pay more attention.

For example, a worker with ADHD may forget to wear PPE or use PPE improperly, reducing its effectiveness. Regular audits and refresher training may help these workers with better practices.

Sensory overload can interfere with an autistic worker’s attention and focus. Here are some ideas to help manage sensory sensitivities:

- Noise-canceling headphones

- Adjustable lighting

- Quiet zones

- Fragrance-free policies

- Climate control

- Flexible work hours

Workers with dyspraxia expend more energy organizing their thoughts and overcoming fine motor difficulties than their neurotypical peers. Finding ways to reduce fatigue – such as regular breaks or ergonomic adjustments – may minimize these challenges.

Dyslexic workers will find it challenging to focus on tasks that require extensive reading and note-taking. Reduce reading and writing demands, if possible. Alternatively, allow the extra time dyslexic workers may need to complete a reading and writing task and set realistic deadlines. The same ideas apply to dyscalculic workers on tasks that require working with numbers.

Recognizing these challenges not only enhances safety but also fosters a culture of understanding and respect that benefits the entire organization.

Building Inclusive Work Systems

An inclusive workplace is one that focuses on the health, safety and well-being of all workers in a neurodiverse workforce. It is possible to build systems to accommodate nearly everyone.

The Principles of Universal Design (see https://design.ncsu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/principles-of-universal-design.pdf) can help you create systems that are accessible to and usable for as many workers as possible. These principles were developed by the Center for Universal Design at North Carolina State University.

Wheelchair ramps are one example of universal design. They accommodate everyone – not just wheelchair users. They benefit elderly people, those recovering from injuries, parents with small children and visually impaired people.

Following are the seven principles and a description and example for each that may aid a worker with a neurodivergent condition.

| Principle | Description and Example |

| UD 1. Equitable use | A design that offers a comparable and non-stigmatizing way to participate.

Example: Voice-activated software for data entry minimizes the necessity of precise hand movements. |

| UD 2. Flexibility in use | A design that provides multiple ways of doing things.

Example: A captioned training video offering playback speed options offers flexibility for better comprehension. |

| UD 3. Simple and intuitive use | A design that is easy to understand regardless of the worker’s education, experience, language skills or concentration level.

Example: A step-by-step procedure kept near a piece of machinery that guides the worker through operation. The procedure should have simple language, visual aids and checkboxes so the worker does not lose their place while working through it. |

| UD 4. Perceptible information | A design that provides several modes of output.

Example: An emergency alarm system with visual signals, auditory alerts and tactile features, such as a vibrating alarm worn on PPE to alert the worker of a safety hazard. |

| UD 5. Tolerance for error | A design that mitigates human error. However, if the error occurs, it does not result in injury.

Example: Hazardous equipment with built-in safety features such as automatic shutoff that turns off the equipment when it detects improper operation. |

| UD 6. Low physical effort | A design that minimizes strain and overexertion.

Example: Adjustable chairs with lumbar support, height-adjustable desks and footrests can mitigate physical strain during long periods of work. |

| UD 7. Size and space for approach and use | A design that accommodates different physical sizes of workers and ranges of motion.

Example: Maintaining uncluttered walkways/work areas allows for easy movement and eliminates trip hazards. It also minimizes sensory overload to those sensitive to visual clutter. |

The Principles of Universal Design provide a sturdy framework for creating a safe, productive work environment.

Protecting and Empowering the Neurodiverse Workplace

A workplace where neurodivergent workers feel supported and understood encourages these workers to embrace neurodivergence as a positive part of their identity. Educating staff about neurodivergence and associated challenges and strengths will also promote understanding among co-workers. Traditional work systems leave neurodivergent workers susceptible to greater physical and psychological hazards than their neurotypical peers. Inclusive work systems create a safer workplace for all.

About the Author: Barb Carr has worked for System Improvements Inc. (www.taproot.com) since 2006. She is a global instructor who teaches safety and quality professionals root cause analysis for better, stronger work systems and performance improvement.