CUSP Basics: Introduction to Human Performance Principles

Have you been involved in an accident investigation? It’s very sad when we find out after the fact that some very simple actions or decisions led to a tragic outcome. Wouldn’t we be better off if we could anticipate incidents and prevent them? In 1990, human performance emerged as a new area of study that uses our knowledge of human nature to prevent events. This article provides some of the principles to start your journey on the road to prevention. These principles are also the basis for the human performance section of the Certified Utility Safety Professional (CUSP) program. To find out more about the program, visit www.usoln.org.

Principle 1: Humans are Fallible. None of us is perfect; we all make mistakes. This very simple message is important because preventing incidents requires counteracting our imperfections. Why do we have somebody else check our work? Why do important calculations require an independent review? Why do we have a supervisor or job leader watch us do important tasks? Why does your computer stop to ask you, “Are you sure you want to delete this file?” Take this notion a step further. Why do we have seat belts in cars? Why do we have safety devices on tools?

One of the most effective ways to apply Principle 1 to your activities is to regularly ask the “what if” question. Knowing that someone might make a mistake, what is the worst thing that could happen to us on this job? Are we prepared for this worst-case event? Use your understanding that people can make mistakes to anticipate and prepare for potential mistakes.

Principle 2: Decision-Making Affects the Outcome. Principle 2 was first revealed in 1990 following extensive study by psychology expert James Reason. This principle involves how the worker is performing the task – is it a skill-based, rule-based or knowledge-based activity? Here are the differences.

Skill-based: The activity has been performed so many times that it can be done without conscious thought – it is basically an ingrained habit. An example would be starting your car. The benefit of skill-based activities is that, from studies, the chance of making a mistake is one in 10,000 attempts. The potential downside of skill-based activities, particularly repetitive work, is boredom, which can lead to incidents.

Rule-based: The activity is performed using a written procedure, manual or work instructions. Rule-based activities generally have a chance of one mistake in 1,000 attempts. If you follow the instructions as written, you will be successful. This is the real trick to having this decision-making mode work for you – make sure that the workers follow their written work instructions.

Knowledge-based: The activity involves a complex situation where no written procedure directly applies. The worker is challenged with drawing from past experiences, knowledge, written guidance from similar situations, and input from others to understand and resolve the situation. These situations have the highest chance of mistakes happening, with an error rate from one in 10 to one in two. To improve the odds in this mode, it is critical to get others involved – including your supervisor – and use a structured problem-solving method to evaluate the situation.

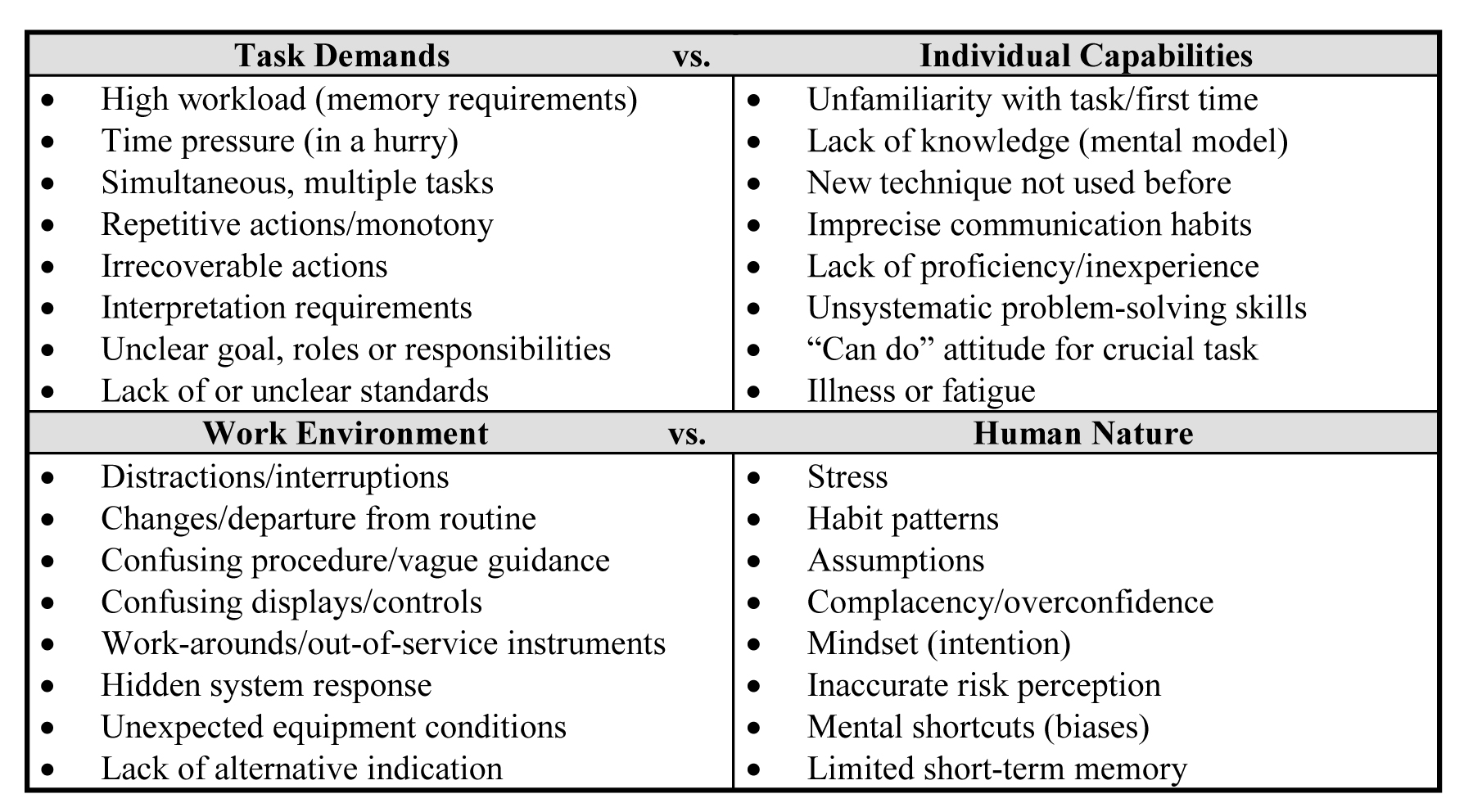

Principle 3: Human Nature Conflicts with Our Work Environment. In today’s complex and technical work environment, this principle is becoming more evident. In addition to being fallible, people have limited memory, biases, habits and challenges with man-machine interfaces. Our technical environment is very demanding, in particular for older workers who are forced to make the transition from manual tasks to computer-aided technology. The table below summarizes some of the challenges.

All of the conditions above are considered error precursors; in other words, the presence of these conditions increases the chance that a mistake will be made. So what can we do?

The key to using Principle 3 to your advantage is to get workers to recognize that the precursors exist, STOP to avoid making a mistake and then implement countermeasures for the concern. For example, we know people have difficulty remembering numerous steps for completing a task. Solution: write down the steps. Don’t reinvent the wheel every time (knowledge-based decision-making); write down the steps and improve the odds of success by moving the task into a rule-based activity. Follow the procedure. If the workers get to the job site, conditions are different than expected and they are installing a new piece of equipment without a vendor manual, the workers need to recognize they are heading into trouble. STOP and get help.

Principle 4: Workers Choose Their Actions Based on Reinforcement. This is a very important principle for incident prevention. This is the root of worker behavior – how are the workers’ actions being reinforced (rewarded)? Are the workers being rewarded for results (getting the work done) or for behaviors (how the work is done)? To prevent incidents, it’s imperative to observe work in the field and reward workers who practice safety and follow the rules. Field observations are also important because of human nature. We can train workers on the right method for a doing a task, but over time, their in-field behaviors may change – for instance, they may find shortcuts. The supervisor must observe work in the field and provide coaching regarding the right way to perform the task. When workers are violating procedures or taking unapproved shortcuts, the first place to look for the cause is in-field supervision.

Human performance is about understanding people and human nature, then finding ways to reduce the chances of making a mistake and/or limit the potential consequences from a mistake. You’ve started the journey just by reading this article. Become a student of people. Observe your co-workers. Think about why you make the choices you do at work. Ultimately, reducing incidents is about finding ways to fight our human nature and Principle 1 – we are all fallible. Be careful out there.

About the Author: Tyrone Tonkinson, Ph.D., P.E., is president of Simple Approach Inc. He has worked for and with electric utilities since 1983, with experience in engineering, QA, regulatory affairs, corrective action, maintenance, work management, industrial safety, project management and human performance. He has provided training and consulting services in a number of areas since 1990, including training for reducing and investigating incidents. For more information, visit www.simpleapproachinc.com.