‘Avoid Contact’: Correctly Understanding the MAD Without a Distance

Electrical workers must recognize that ‘avoid contact’ requires them to rubber up or cover up – including when contact is possible with secondary voltages.

For decades, air has been used to effectively and inexpensively maintain phase-to-phase and phase-to-ground clearances of overhead distribution and transmission power lines and electrical equipment. Air’s extremely high resistance offers excellent protection against the passage of current. The greater the nominal system voltage, the greater the air gap required to prevent a flashover and short-circuiting.

Due to its dielectric properties, air is also used to protect workers from electric shock. Incident Prevention readers who work in the electric utility industry are familiar with the term “minimum approach distance” (MAD). Workers in industries that incorporate NFPA 70E into their electrical safety programs may use the term “restricted approach boundary” (RAB). Although there are slight differences between the two, both the MAD and RAB establish a physical air gap between the qualified worker and exposed energized parts or lines to prevent the worker from inadvertent shock. Readers should note that electric utilities are not covered by the scope of NFPA 70E; however, several portions of the standard offer useful information that utility organizations may want to consider.

Two Critical Components

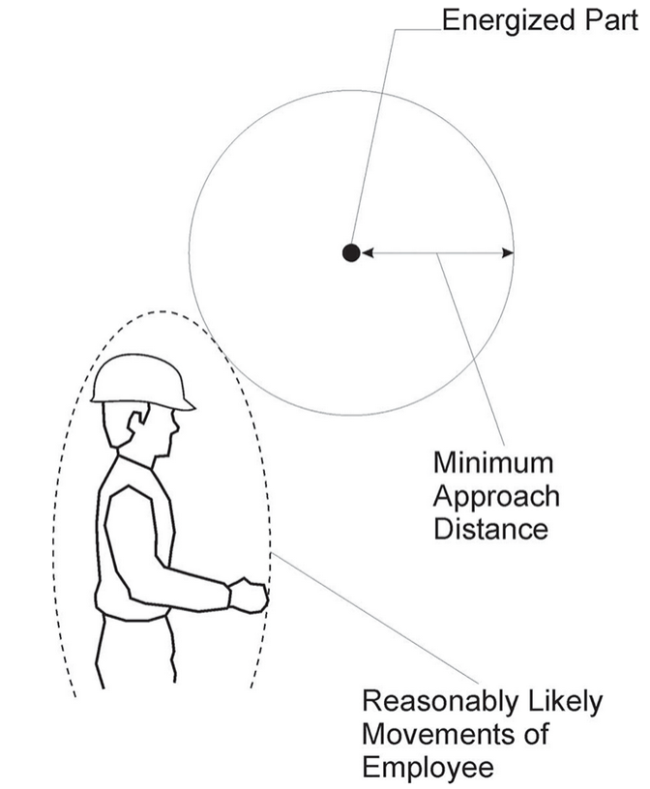

MAD and RAB incorporate two critical elements to keep workers safe: an electrical component followed by an ergonomic component.

The electrical component – also called the “minimum air insulation distance” or “MAID” – serves to prevent an arcover/sparkover/flashover, in which the voltage stress is greater than the dielectric strength offered by a certain spacing of air. This phenomenon is referred to as the “voltage breakdown of air” or “dielectric strength of air.” Remember that while air offers superb resistance to the passage of electric current, it has voltage-based limitations much like any other insulating material.

The ergonomic component is a safety buffer known as the “inadvertent movement factor.” It targets human error when work is performed near energized parts, mitigating simple employee mistakes, such as overconfidence, loss of situational awareness and incorrectly calculating the distance to an exposed part. This component also accounts for unexpected body movement (e.g., reaching for tools or materials, adjusting PPE, swatting at flying insects).

When the electrical and ergonomic components are combined, a corresponding MAD/RAB is determined. Figure 1 shows the MAD/RAB of the worker’s body in relationship to an exposed energized part.

OSHA’s MAD can be derived via two methods. The first is to employ mathematical calculations. For elevations up to 3,000 feet, use Table R-3 (AC voltages) or Table R-8 (DC voltages) found in 29 CFR 1910.269. Calculations for elevations above 3,000 feet must include an altitude correction factor along with overvoltage transient considerations for voltages greater than 72.5 kV. The second method is to utilize the alternative distances listed in Table R-6 for voltages of 72.5 kV and less; for 72.6 kV to 800 kV, use Table R-7.

NFPA 70E’s RAB distances are predetermined values located in Table 130.4(E)(a) for AC systems and Table 130.4(E)(b) for DC systems. The distances listed in both the OSHA and NFPA tables are limited to work locations with a maximum elevation of 3,000 feet.

Crossing the MAD/RAB: Prescriptive Action Required

As mentioned, the MAD/RAB is established to prevent unintentional contact by providing an adequate safe work zone between the worker and the energized exposed parts. Crossing the MAD/RAB must be treated the same as making intentional contact with the energized parts.

This important point needs to be emphasized: The purpose of the MAD/RAB is to prevent unintentional contact – but entering the MAD/RAB must be treated as making intentional contact.

That is because both OSHA 1910.269(l)(3)(iii) and NFPA 70E 130.4(G) establish prescriptive actions to be taken before a qualified electrical worker is permitted to violate the MAD/RAB: either the worker is insulated from the exposed energized parts, or the exposed energized parts are insulated from the worker.

The first action is accomplished when the worker dons voltage-rated rubber gloves with protectors and, if necessary, rubber sleeves. To complete the second action, install voltage-rated rubber blankets and/or hose sleeves over the exposed parts. An old industry saying – “Rubber up or cover up” – was birthed from this regulatory mandate.

Easy Concept or Confusing Directive?

For most voltages, the OSHA and NFPA 70E tables define a specific minimum spacing listed in feet or meters. The greater the voltage exposure, the greater the distance needed to protect the worker. This is true with most MADs/RABs. An exception occurs in the two standards where increments of length establishing a physical gap have been replaced with this ambiguous phrase: “Avoid contact.”

In Appendix B to 1910.269, “Working on Exposed Energized Parts,” OSHA includes the following footnote: “For voltages of 50 to 300 volts, Table R-3 specifies a minimum approach distance of ‘avoid contact.’ The minimum approach distance for this voltage range contains neither an electrical component nor an ergonomic component.” That means no safety buffer exists. OSHA applies “avoid contact” from 50 to 300 volts, while NFPA 70E applies it from 50 to 150 volts.

At face value, “avoid contact” may appear to be an easy safety concept that needs no explanation. And when electrical workers are asked what “avoid contact” means to them, “Don’t touch it” is a common response. This is logical since neither OSHA nor NFPA 70E provides a technical definition of the phrase. Without clarification, employers and workers are left to interpret its meaning on their own.

Per Merriam-Webster, “avoid” means “to keep away from”; “contact” is defined as “the junction of two electrical conductors through which a current passes.” Consequently, when OSHA and NFPA 70E use the two words together, workers are guided toward an incorrect and dangerous interpretation. They consistently interpret “avoid contact” to mean nothing more than a warning to be careful or refrain from touching an energized part.

Does a warning constitute an adequate barrier between life and death? The obvious answer is no, with fatality data supporting this position. Let’s recall that although the purpose of the MAD/RAB is to prevent unintentional contact through safety margins, crossing it requires precisely the same practices as intentionally contacting exposed energized parts. To enter the MAD/RAB, the worker is required to insulate either themselves or the parts (i.e., rubber up or cover up). Whenever practical, workers should do both.

Secondary Voltages are Hazardous

Some individuals, especially those who work around primary voltages, might think 120 volts isn’t particularly dangerous. Many of us have even said, “It’s only 120 volts” or “It’s only secondary voltage.” But when we review OSHA’s preamble to the final rule, we find that at least 25 electric utility workers died after contact with “only” 120 volts (see www.osha.gov/laws-regs/federalregister/2014-04-11).

OSHA also provided this clarification in the 2014 final rule: “The hazards posed by installations energized at 50 to 300 volts are the same as those found in many other workplaces. … The employee must avoid contact with the exposed parts, and the protective equipment used (such as rubber insulating gloves) must provide insulation for the voltages involved.” This means the worker must implement some type of active countermeasures that will prevent inadvertent contact with lower yet still hazardous voltages.

This concept is better understood by reviewing Figure 2, which shows the practice of rubber up and cover up while a worker takes voltage readings of an uninsulated, overhead, single-phase 120-/240-volt line. Note that while Figure 2 depicts bare wires, workers should wear rubber gloves whenever handling energized triplex or quadruplex secondary service drops. That’s because the insulation can become brittle due to weathering and crack while being handled.

What about working with equipment housed inside cabinets or enclosures, as shown in Figure 3? If the task is troubleshooting a 480-volt starter, Class 0 or 00 rubber gloves are adequate to protect the worker’s hands within the RAB of 12 inches. But in this example, are gloves alone adequate to protect the rest of the body? The answer is no due to the exposed parts mounted on the inside of the hinged door. Door hardware is normally energized at 120 volts, so the corresponding electric shock distance is “avoid contact.” If the worker’s understanding is “don’t touch it,” they would likely position their body to avoid touching the door-mounted components behind them. However, the worker could lose focus, become distracted and then step back into the door, or a breeze could move or close the door on the worker. Although the worker’s intention was to avoid contact, inadvertent contact occurs due to unconsidered factors.

A worker who understands the following is likely to take the action necessary to avoid making contact:

- The risks and severity of contact with secondary voltages.

- The purpose of the MAD or RAB (i.e., to avoid inadvertent contact with energized parts).

- The regulatory requirements that must be met to cross the MAD or RAB, either intentionally or unintentionally.

By placing a voltage-rated sheet or blanket over the exposed door parts, as shown in Figure 4, the worker prevents accidental contact and fulfills the MAD/RAB entry requirement to insulate exposed energized parts from themselves.

Conclusion

Electrical workers must be trained to understand that “avoid contact” does not simply mean “don’t touch it.” Workers also must be taught to properly respect secondary voltages, which can pose extreme health and safety hazards, including death. This pragmatic approach will help employers bridge knowledge gaps and reduce the number of preventable industry accidents and injuries.

About the Author: George T. Cole, CUSP, CESCP, CESW, CIT, SGE, is an instructor and electrical safety consultant for e-Hazard. Reach him at george.cole@e-hazard.com.