Assimilating Short-Service Employees Into Your Safety Culture

Culture is one of the most significant drivers of an organization’s safety performance. It can take time to build a safety culture, and it also takes time for employees to assimilate into an existing culture after beginning work for an organization. This poses a serious challenge for organizations that regularly scale to meet project demands. An influx of short-service employees (SSEs) often coincides with an increase in incidents. While there are a number of reasons for this – such as poor hazard recognition – one significant reason is that SSEs have not yet assimilated into the existing culture’s standards of safe operations. Despite efforts to overcome this problem, many companies continue to report that it remains one of their greatest challenges. After examining SSE programs implemented by different organizations, my colleagues at The RAD Group and I have identified criteria for an SSE program that helps new employees more effectively adapt to a company’s safety culture.

The Root of the Problem

Once a strong culture is in place, it is like a hidden force guiding people’s decisions to work safely. However, it takes time for people to fall under the influence of a safety culture, and in the meantime they may work in a way that does not align with their employer’s standards. The root of the problem, of course, is that SSEs by definition have not been in the organization long.

To better understand and respond to this enduring challenge, it helps to address three questions:

1. How do people assimilate into a culture?

2. Why do some SSE programs fall short?

3. What kind of program would more effectively assimilate SSEs into a safety culture?

Let’s take a look at the answers to these questions.

Culture and the Mechanisms of Assimilation

Culture can be thought of as the taken-for-granted way of doing things within a social space. “Taken for granted” means that people behave and make decisions according to shared, informal guidelines – often referred to as “unwritten rules” or “social norms” – without pausing to consider whether the guidelines are right or wrong. In a safety culture, these social norms range from following safe work procedures to exercising stop-work authority without hesitation.

“Enculturation” is the process of learning and accepting the norms of an existing culture. During this process, a person gradually establishes what is acceptable and unacceptable to others in that culture and eventually adopts those same norms – taking for granted that they are the appropriate way to behave. This can happen when a person moves to a new geographical region or begins working for a new company. You can think of this gradual process as having two phases: exploration and automation.

During the exploration phase, a person observes what others do and say to discern what they actually believe to be acceptable, unacceptable, desirable and undesirable. These subtle cues are found in others’ informal comments, behaviors and decisions. They often are not communicated intentionally and can even conflict with statements of priority that are made in formal contexts, such as safety meetings or training sessions. According to Edgar H. Schein, in his book “Organizational Culture and Leadership,” such cues include:

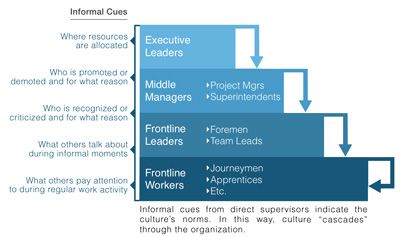

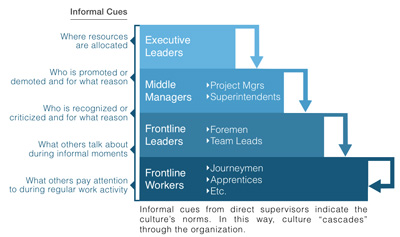

• What others pay attention to.

• What leaders talk about during informal moments.

• Where resources are allocated.

• Who is recognized or criticized and for what reason.

• Who is promoted or demoted and for what reason.

Newcomers to a culture are attuned to these subtle and informal cues, which, over time, form their understanding of the group’s norms.

Also during the exploration phase, people test their understanding of the culture’s norms by attending to how others react to their behaviors and comments. For example, a new SSE may make a statement and then ask himself, “Did my supervisor brush me off when I said that?” Ask a child who has transferred to a new school, and he or she will attest to the stress and struggles that can accompany the exploration phase.

Once a person develops an understanding of the social norms, and then successfully tests that understanding among members of the culture, the most challenging phase of enculturation is over. Much like other things at which a person becomes proficient – like driving a car or speaking a new language – aligning with cultural norms eventually becomes automatic. It no longer requires conscious, deliberate effort. Instead, it becomes a taken-for-granted way of doing things in that social space. This is the automation phase.

With an understanding of these phases, we can evaluate common SSE programs to determine where they might succeed or fail with respect to assimilating people into an existing culture.

A Review of Common SSE Programs

After conducting a survey of nine organizations’ SSE programs, my colleagues and I found nearly all were built around two components: orientation and mentorship. These programs start with a classroom orientation before employees set foot on the job site. During these half-day to two-day training sessions, the company’s safety values are formally communicated and it is explained to employees that they are expected to work safely. Sometimes high-level leaders appear in person or via prerecorded videos to add emphasis.

Most of these SSE programs also formally designate the employee’s direct supervisor as a mentor. Except in the case of two of the nine programs, supervisors are not given training or other support to serve as a mentor. As a result, in practice, mentorship begins as a brief meeting the first day on the job, during which the supervisor and SSE sign a document affirming that they have read and understand the company’s policies surrounding SSEs. Then the supervisor keeps an eye on the employee and corrects mistakes. In these programs, mentorship is equivalent to enhanced supervisory oversight.

While orientation training and enhanced supervisory oversight help to mitigate the risks that stem from new employees’ inexperience, these programs – for the following three reasons – often fall short when it comes to assimilating SSEs into the safety culture.

• Enculturation happens over time. More specifically, the two phases of enculturation – exploration and automation – take time. Social norms are gradually inferred from informal cues, tested in various contexts and then eventually come to be taken for granted. One-time events like orientation training are, on their own, too brief to facilitate a person’s understanding and adoption of an organization’s cultural norms.

• Enculturation happens on the job more than it does in the classroom. In the majority of SSE programs we reviewed, safety standards are communicated during classroom training and then reaffirmed in a short meeting with the supervisor during which he or she reviews SSE documentation. However, throughout the exploration phase of enculturation, the informal cues that SSEs observe while working around others are taken to be true indicators of the culture’s norms.

• Enculturation is driven by direct supervisors. From the perspective of frontline workers, a direct supervisor’s expectations and values are of utmost importance. This is the person who can make their life miserable or recommend them for a promotion, and this is also the person with the most day-to-day influence. Managers and corporate leaders may have the greatest scope of influence over an organization’s culture, but most of that influence is indirect. Culture cascades through levels of direct supervisors.

While well-suited to improve new employees’ hazard recognition and help supervisors correct risky behavior, SSE programs can fall short of assimilating people into a safety culture.

A Different Strategy

Given the mechanisms by which people learn and adopt the norms of those around them, a strategy with the following characteristics would more effectively bring SSEs into an existing safety culture.

• Sustained: Organizations should plan for their enculturation efforts to last at least four weeks.

• Interpersonal: Direct supervisors are the agents of enculturation. Organizations should take steps to foster rapport and a foundation of trust between direct supervisor and employee to enhance supervisor influence.

• Informal: Much of the exploration phase is driven by informal cues from direct supervisors and co-workers about what is actually expected of the SSE. According to a 2002 article by Dov Zohar published in the Journal of Organizational Behavior – titled “The effects of leadership dimensions, safety climate, and assigned priorities on minor injuries in work groups” – supervisors must understand the significant impact of, for example, what they focus on outside of safety meetings and where they allocate resources.

• Unambiguous: Leaders should communicate and behave in a way that clearly demonstrates the culture of safety, taking the guesswork out of the exploration phase. When SSEs see clear and consistent cues about the culture’s norms, they assimilate faster.

In our survey of SSE programs, my colleagues and I encountered two organizations that achieved a significant reduction in incidents during employees’ first 90 days on the job. They did this by changing their programs to incorporate these four characteristics. Like others’ programs, theirs were built around orientation training and mentorship, but certain modifications made them more effective at enculturation.

First, the organizations developed weekly on-the-job training modules to reinforce and build upon what was learned during upfront classroom orientation. Once a week for three to five weeks, SSEs would meet one-on-one with their supervisor to review job-specific hazards and mitigation practices, and also to give the SSEs an opportunity to ask questions and describe hazards that they had recognized during the previous week. This was first envisioned as a way to improve job-specific hazard recognition, but it produced a secondary effect. As a result of regular interaction, employees and supervisors came to know each other personally, had informal conversations and established a level of trust such that SSEs were comfortable approaching their supervisors about safety issues that they may have otherwise remained silent about. In short, by increasing the amount of interaction between supervisor and SSE, supervisors become more effective agents of enculturation.

Second, frontline supervisors were trained as mentors. In addition to teaching them to administer the weekly one-on-one training sessions, supervisors were taught to reinforce safety expectations regularly and during informal teaching moments. In other words, supervisors learned how to provide unambiguous cues so that SSEs would quickly understand the norms of the existing safety culture.

The research conducted by my colleagues and I found that many organizations can more effectively assimilate new hires into their safety culture by making a few strategic changes to their existing SSE programs. For most, the foundation is already in place, and the benefits of having a workforce that is more fully integrated into the safety culture can significantly outweigh the efforts required to make those enhancements.

About the Author: Phillip Ragain is the director of research and training development at The RAD Group (www.theradgroup.com), which specializes in human performance, behavioral safety and safety culture solutions. Ragain also is the author of numerous articles on human performance in safety, communication and organizational ethics, and he has developed training programs that are currently used by organizations around the world.